Williamsburg National Park skyline sunset from my window.

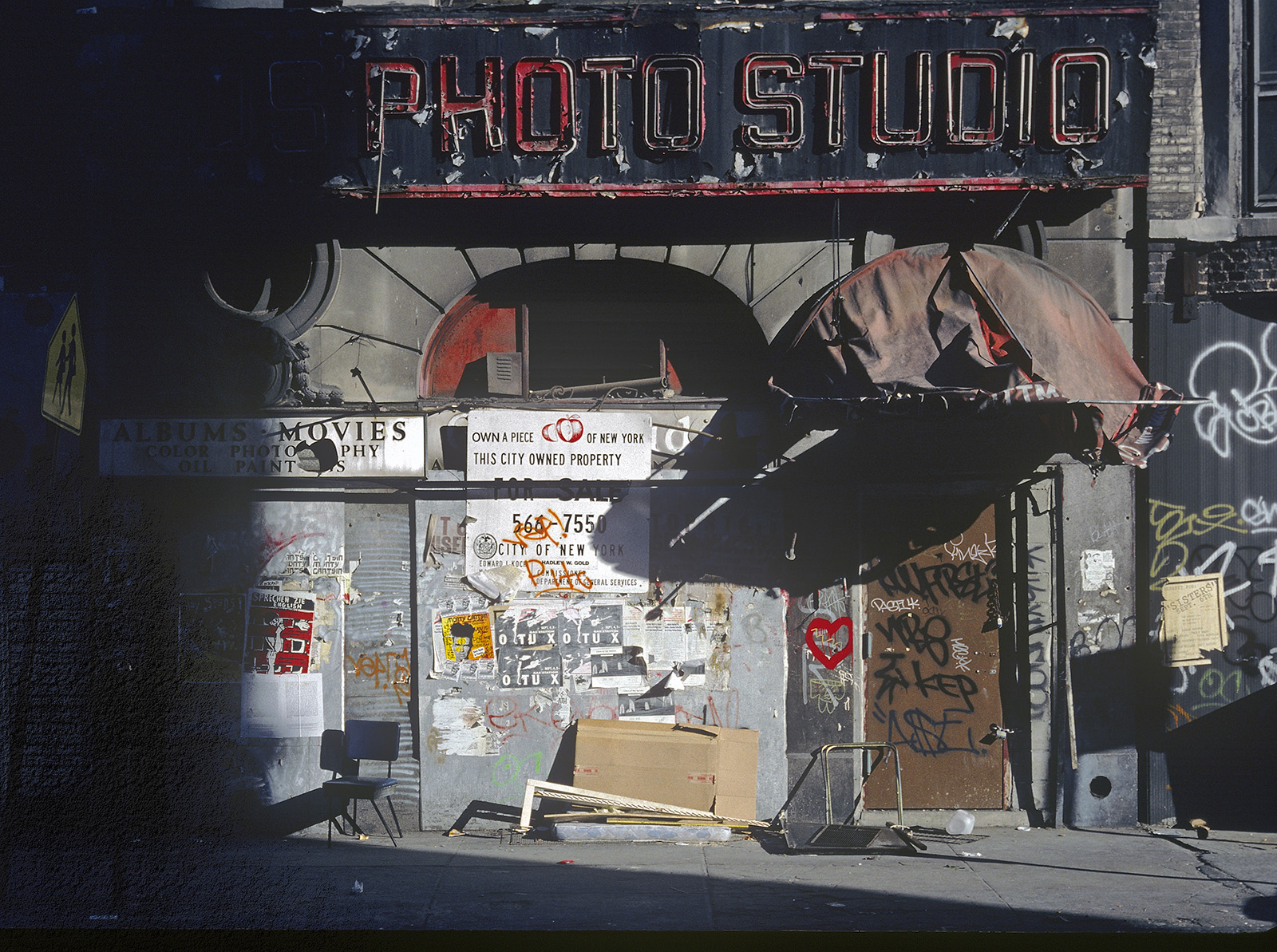

The Ko Rec Type Plant on Kent Ave. – Monument to the white out of our neighborhood by artists, hipsters, developers, bar owners and landlords.

The view out my window on Union Ave. – here local members of the Williamsburg Monument Conservancy discuss the waterfront, six blocks to the west, where some of them worked.

“For a long time Brooklyn was “cool” because it wasn’t.” – TwoShoes

Williamsburg National Monument: The Williamsburg Park that Made Brooklyn a Brand of Hipsters

INTRODUCTION

But first allow me this – I didn’t want to write a long introduction to such a negligible and small book of shots. There’s no reason to write it. There aren’t the ears or eyes for it. But to deny the absurdity of what I know to be true is more absurd, almost unbearable. Speaking of which, I was finally forced to hit the trail, synchronous with the formation of these sentences.

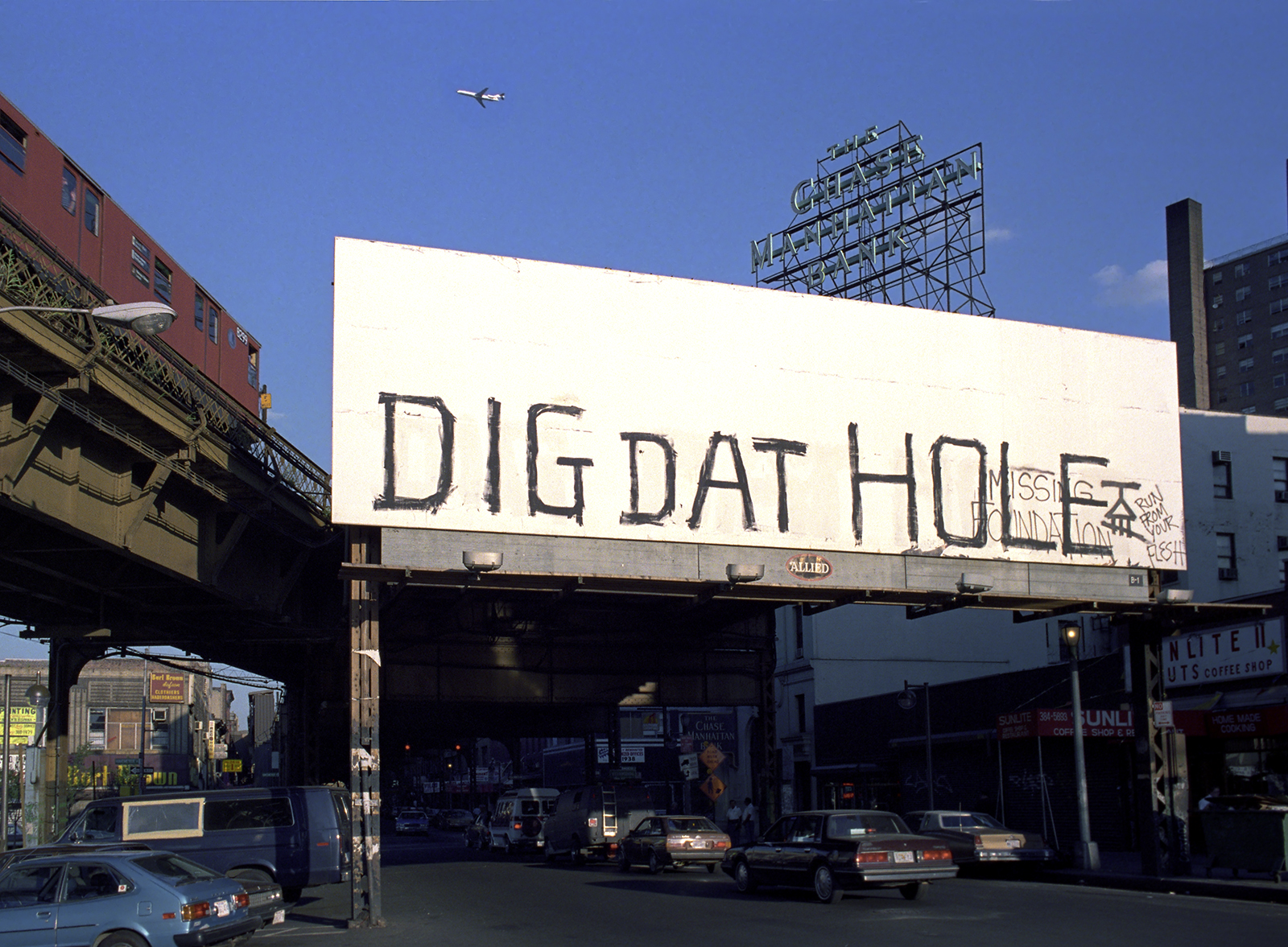

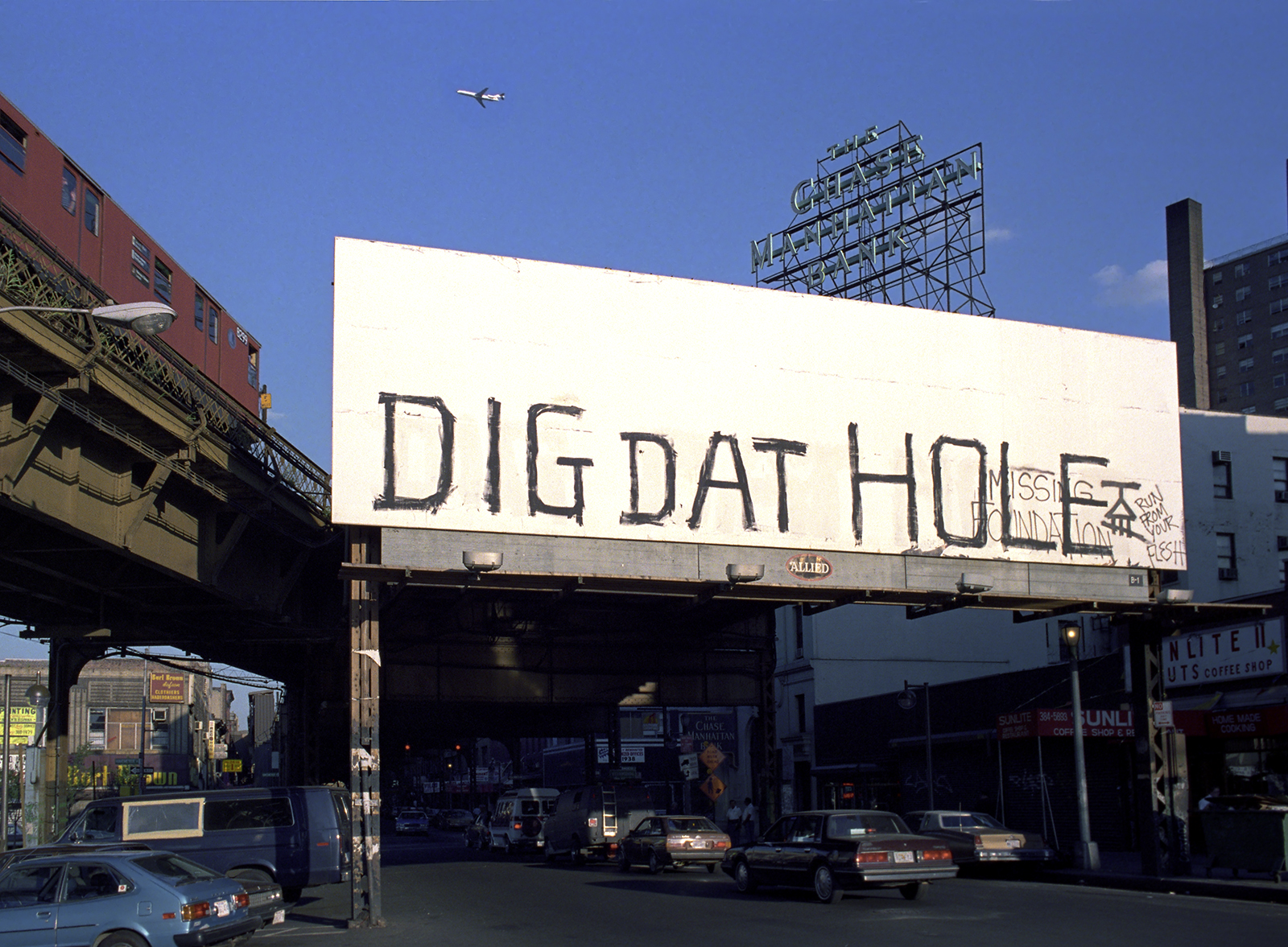

Realizing no one has the patience for specifics, but, at the same time, thinking there’s way too much shorthand out there, I’m not gonna tweet in my discourse even if that’s expected. In this moment Brooklyn Industries is a t-shirt and Northside Piers is a condo tower and I think this needs some interpretation, that you just can’t get at your local genius bar or in hipster heaven, where the history of the world began around 1980.

Please accept without any stupid connotations concerning truth and reality, that, if i were an artist, i would be a reality artist, a source artist. Up front, i’m predisposed to a view that the city is a museum of itself and much of my thinking arises out of reciprocating contact with the world itself, not its many portrayals.

Awfully unreconstructed, I want to be that way, because it’s better than a make over. I have no interest in reinvention, reuse, repurposing, rehabbing and remakes, empowerment, or the awesomeness of, well, everything. I will defer to ridiculous, even embarrassing, as proper terms for recent times and the rise of of the gentry, and their blind tech-love.

We’re all familiar with what official history documents by those, I’m not acquainted with, that do the remembering. Actual histories may become artesian as they get buried as a matter of course, but they don’t have to remain so. They can emerge as springs, or in my case, leachate, in, for example, a book.

Williamsburg National Monument is a look back on the East River waterfront during the early eighties. It’s a look at the the bridge named for that neighborhood and its single most significant monument. It’s a documentary postcard of the industrial environs of the Williamsburg waterfront thirty years ago. Well before the Greenpoint-Williamsburg Contextual Rezoning of 2005 and the general Ignominious Era of Reinvention, we lived happily buried in a thick neighborhood mix of enclaves and industry. We never wanted, everything was there for us – work, cheap slum housing and a very real social life. Soul, authenticity and connection, the list of amnesties was endless and free. The food was good, if scarce, shelter, a bit substandard, but all at reasonable prices. And it was not necessary to leave in order to find the city of New York. There was the relativity we don’t have today.

OILY DAYS

In 1800 Richard Woodhull owned the ferry to New York at North 2nd Street. He hired Colonel Williams to lay out a fashionable suburb for New York across the river on the 13 acres of waterfront he owned. Naming it Williamsburg, by 1806 it had become a monument to complete failure. But others saw the same potential as Woodhull and eventually Williamsburgh would catch on with the gentry. The next step seemed profitably logical and people like Andrew Greeley invested there, betting the waterfront would be a fancy place of leisure and home life.

By the 1830s, Irish, German and Austrian business types established themselves in Williamsburg. It became a fashionable resort that attracted such notables as Commodore Vanderbilt and railroad magnate James Fisk who built shore-side mansions. Gilded Age barons like William Whitney stayed in elegant resorts along the waterfront, one of which even featured a resort hotel combined with a circular amusement railroad at North 5th and Kent, which, by 1870 was a major marine rail transfer station that wasn’t amusing. But it was very dirty, profitable and the trains were real.

During its period as part of Brooklyn’s Eastern District, Woodhull’s 13 acres would achieve remarkable industrial, cultural, and economic growth, and local businesses thrived. The first global recession, the Panic of 1851 hit, and any speculative real estate money dried up. Williamsburg never looked back and would go on a spectacular run as the classic, blue collar industrial-age urban ghetto, and, particularly after the bridge opening, it became more like the Lower East Side – dense, immigrant, lower-class, and ethnically defined. The bridge quickly doubled the population of Williamsburg into, then, one of the most densely populated places on earth. The Eastern District’s wealth was in manufacturing and transportation, as well as, its mass of low wage workers. Dreams of resort days and a suburban refuge for New Yorkers, were now instantly replaced with purely heavy industry, as industrialists like Pratt, needed thousands of acres, close to water and rail for refineries, along with many thousands of low wage local workers.

Williamsburg National Monument stood for 23 years as a memorial to this forgotten Eastern District which, it is popularly said, is where ten percent of the nation’s wealth was once concentrated. That is to say, industrial wealth.

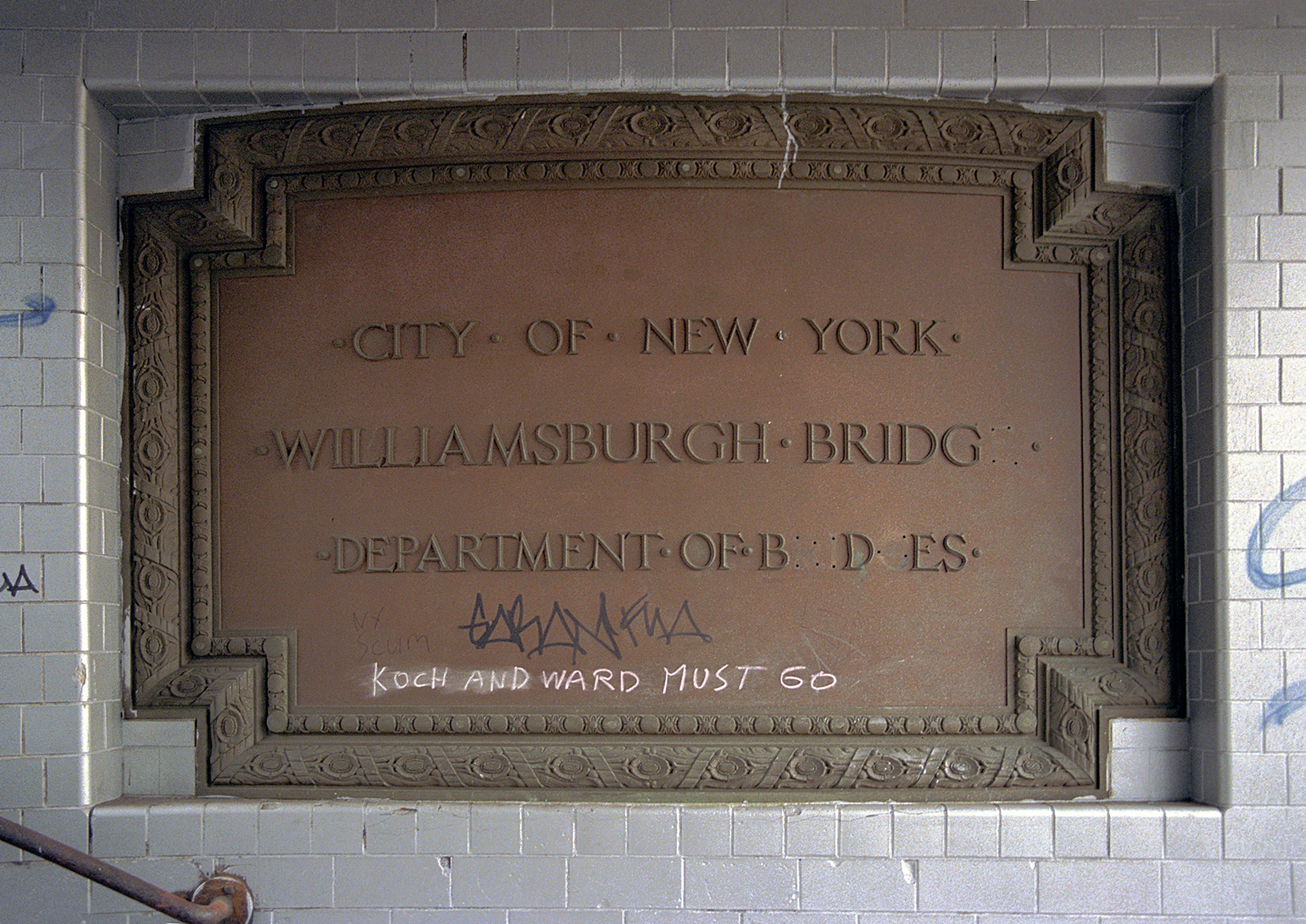

The bridge itself remains, as the central formation of the monument, although in a greatly altered shape. The LES/Williamsburg connector stands for the neighborhood itself. Built during a time of horse, wagon, buggy, and steam locomotives, the bridges of the East River were so brutally sturdy, they’ve handled anything thrown at it – big rigs, ten car subway trains, and pedestrians and bicycles. The Williamsburg, distinguished by its bare bones utility, in comparison to bridges north and south, is not pretty, but gets the job done. I don’t know if anyone noticed but most of the old bridge is gone, it’s complex latticed steel approaches now a freeway style runway. It did need work.

Williamsburg Bridge in 1999 – the east tower is shrouded because the artist, Christo, and his wife, were into proper lead paint removal, and were hired by the city to shroud the bridge in fabric. But seriously, the complete rehab of the bridge began in 1992 when Williamsburg was still entirely working-class. There was no protection from falling lead particles on the east approach over the neighborhood, like i said we were always forgotten back then – at least until they got caught/reminded of the problem.The Dominoe Plant was alive during the WNM years, finally succumbing in 2004.

“Surrender of the City Beautiful to the City Vulgar.” is how John DeWitt Warner described the bridge after its building. Definitely contextual to North Brooklyn’s brutal utility where power stations, refineries, factories, chimneys, and church spires dominated the skyline, the same way condo towers do today. However Mr. Warner’s comments weren’t a cry for redevelopment in 1903, more of an observation.

Williamsburg Bridge history: in 1896 construction begins, in 1989 Brooklyn becomes part of New York and in 1903 the bridge is complete. Named for the neighborhood, most likely coming from the fact that only Brooklyn wanted it, and New York didn’t care, the Williamsburg was built cheaply without architectural considerations. It was big and useful. Although its lack of galvanization would come back to haunt it.

Was the bridge so utilitarian, no one remembers now, that most of it is gone?

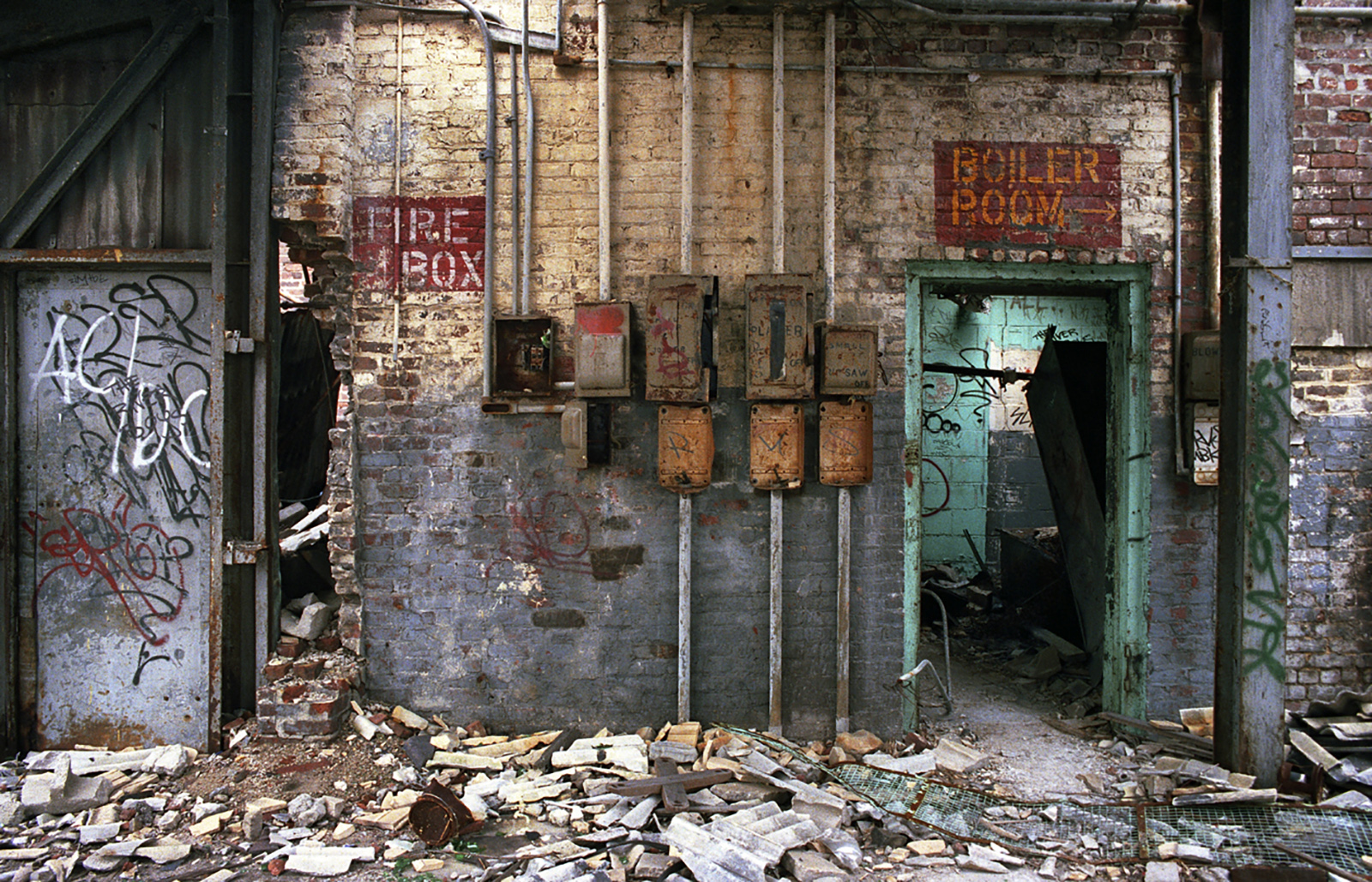

THE MONUMENT

The Williamsburg National Monument was based on the psychogeographic Theory of Organic Descent that was wildly popular between 1970 and 1990. Nowhere was this theory showcased better than in the Monument’s wilderness area located in the old Brooklyn Eastern District Terminals Wilderness Area. These badlands, the larger and now forgotten predecessor to the new East River Park, or as many locals refer to it, “Final Solution Park,” was the very soul of one of the most respected examples of the Geography of Organic Descent, in America (hats off to Johnstown PA, Butte MT, Braddock PA and Cleveland, OH).

Williamsburg National Monument, a landmark of its time (1983-2005) stretched along the Williamsburg Brooklyn waterfront just north and south of the bridge aside Kent Ave., in the time before the finest harbor in America had lost a lot of its utility to the good view, leisure and shopping. From the Navy Yard at Division Ave. to North 11th St., or, what is essentially the north and south sides of the Williamsburg neighborhood, is where the Brooklyn side of this bi-borough park is located. The LES side of the Monument was centered around the anchorages in New York. The namesake bridge is the connector and centerpiece of the Monument, and was the single largest formation in the preserve. To reiterate, the bridge is so utilitarian, does anyone realize that most of it is gone? Or is it so utilitarian that no one cares? Unfortunately, with the demise of the Conservancy during its humiliating defeat in the Hipster Putsch, these questions cannot be answered.

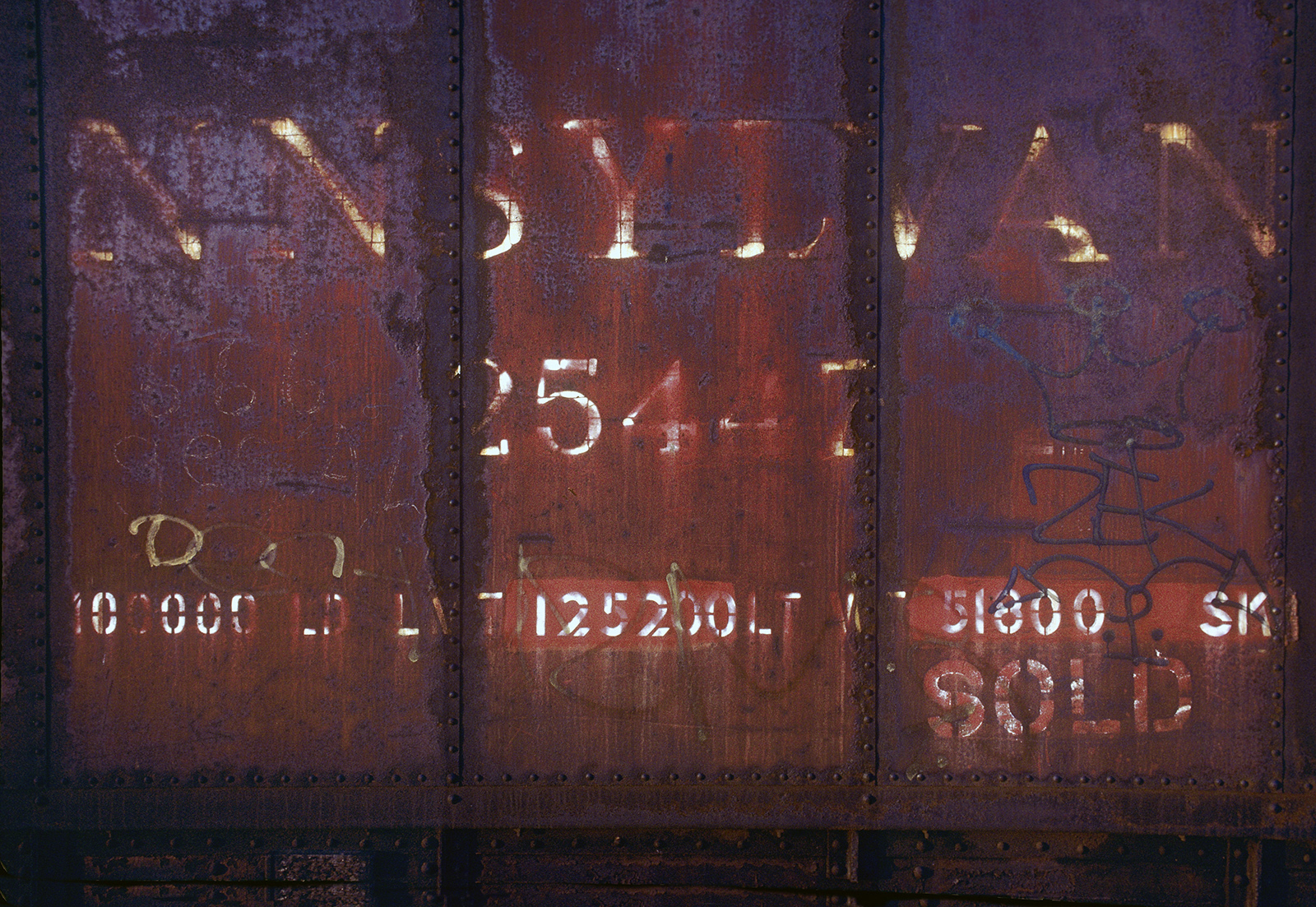

Back in the 80s the Brooklyn waterfront to the immediate north and south of the bridge was a mix of operational and dead industry along Kent Ave. The largest dead zone was the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminals marine rail facility which ran from North 5th to North 11th Streets along Kent Ave. BEDT ran floatcar operations along New York harbor, and the Kent yards were its biggest facility. A lot of the industrialized M-4 zoned real estate were dead zones along Kent Ave. and were in a continual state of organic descent, unprotected except by a bad economy, they somehow managed to decline peacefully, if molested, for 22 years. But others like Domino Sugar were operational, along with some waste transfer stations, warehouses and factories, making the monument a unique living industrial environment, one that had seen better days but was operational during its descent. And this was key to understanding one of the Institute’s prevailing concerns – functioning in hard times.

Schaefer Brewery on the South side of the bridge was near the Monument’s terminus at the old BMT Power Station, and, across the street from the old Allied Signal Company. The Brooklyn Navy Yard, not part of the Monument, continued industry’s relentless lining of New York harbor and formed the south boundary of the monument.

Schaefer Brewery, closed in 1978, stood abandoned for many years. Today Schaeffer Landing, a luxury condo tower, stands in for the old brewery. Honoring the history of the site, each floor – 26 in all – commemorates each year the Schaeffer Brewery lay dormant within the Monument. It is here grateful, awe-struck locals are allowed to share a waterfront terrace as a public space with the newly arrived gentry, but, of course, under the types of restrictions the Monument Conservancy would never agree to.

It’s these types of disagreements, combined with the general outside culture reaching such a high degree of non-critical thought, that, thankfully, completely shut the Conservancy out of all decisions about a waterfront it formerly guided. Enormous philosophical differences, like the Newtowners penchant for not leaving a trace of authenticity or character only meant the Conservancy was happy not to participate in its own demise, emphasizing the glaringly self-evident truth, there would never be any connection between the authentic and the gentrified Williamsburg and the LES. When your sense of city history begins upon your arrival it follows you sit on a throne of bull shit. But that only counts for a petty thing like your perception of reality which you find no need for. Newtowner, I just want you to know that there is no doubt you are still cutting edge brilliant, despite your insecurities.

Before the time artists and developers were entwined, a Burger King mogul technically owned the BEDT lands. The Hasidic security patrolled in old Lincoln Continentals, and let the Monument and Conservancy operate as usual. That kind of cooperation between private business and the low-life public would be unheard of today.

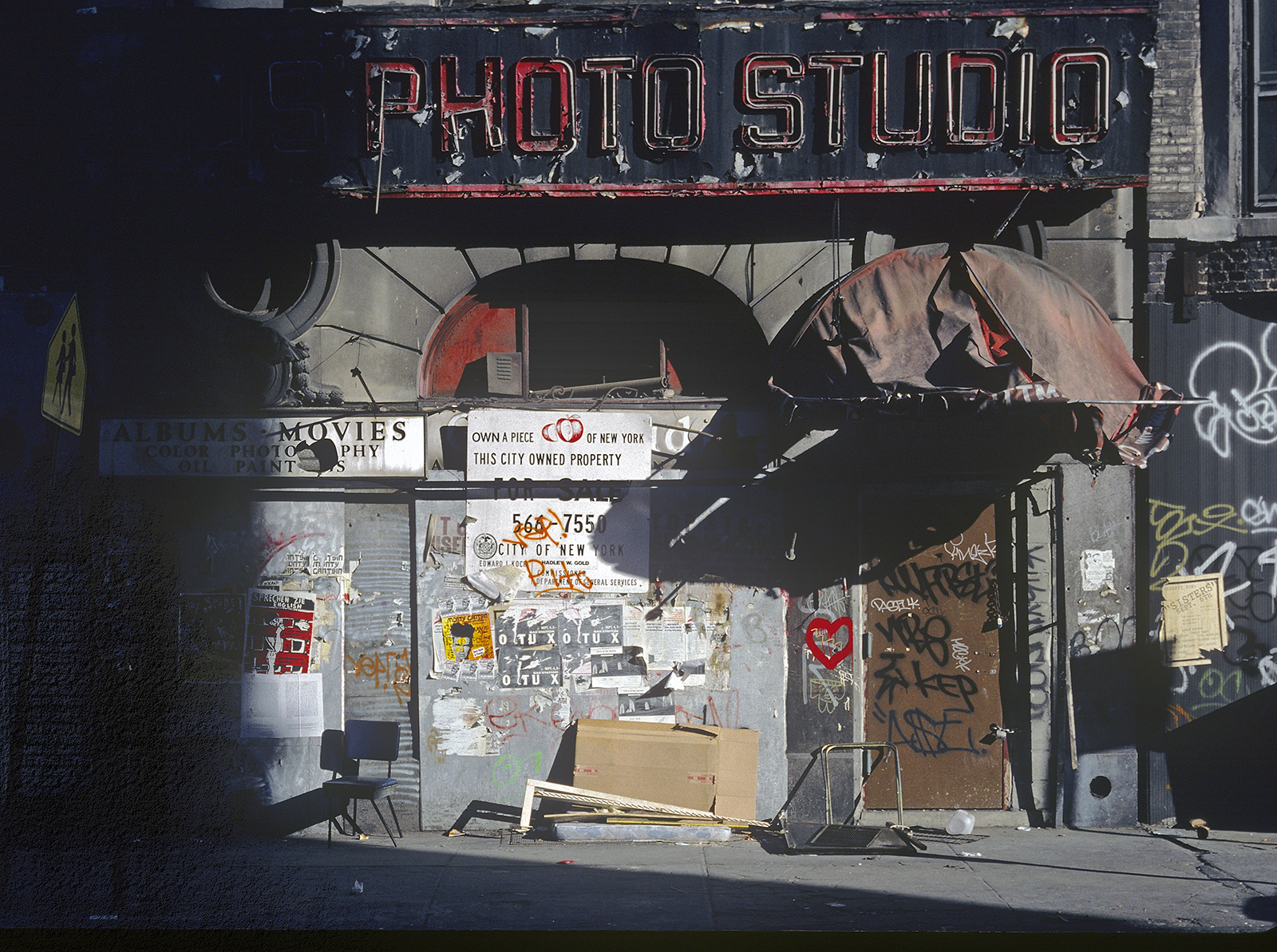

The Monument also included the Lower East Side neighborhood anchorage on the New York side of the bridge. Known as the Blightlands this area of the Monument was more residential and less devolved into nature as the Brooklyn waterfront side, and its views weren’t as good (unless you call looking at Brooklyn good). But the Blightlands around the Williamsburg Bridge anchorage on the LES, featured many hoodoos and other wild erosional formations which are now gone due to the extreme forces of a real estate climate warming to the idea of flipping slums.

The bridge itself is probably the main feature of the park and, still to this day, is very accessible. However the ancient bridge art of pictographs were washed away in the First Grand Cleansing by the Great Father Giuliani.

(The Conservancy official policy on pictographing is, if it is done on abandoned, doomed land, there is nothing wrong with it. But established living monuments built by dead and anonymous toil should be left alone.)

The spiritual center and the park’s headquarters, the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminals & Badlands, was the last rail facility in New York City to use steam locomotives, that was in 1963. Twenty years later BEDT shutdown for good. Just after this I began to shoot the Monument. North of BEDT was Palmer’s Landing, the Northside Piers and the Cross Harbor Railroad – more sacked temples of heavy industry, where more rail marine terminals orchestrated trains, tugs, barges and ships into giant floatcar operations that brought in raw materials to, then, be shipped back out as a myriad of finished products. BEDT also had a flour depot and sulphur plant, and many of us remember its coal storage facility set deep into the residential North 4th neighborhood around Berry St.

BEDT shutdown for good in 1983 and Williamsburg National Monument was born. Here, the Williamsburg National Monument Conservancy, whose headquarters and offices were sacked at the height of the Hipster Putsch, were located. The Conservancy survived until 2005, the year of the Golden Gelding, when all final traces of the neighborhood’s history were deleted. A couple of rails embedded in concrete and brick is all that remains of the BEDT at the new East River Park, also known as the Jarring Juxtaposition Park.

After the flipping from the sublime to the luxurious, and, not preserving the context of the neighborhood one bit, nor providing the promised affordable housing, the condos, north of BEDT, Palmer’s Landing and Northside Piers, honored themselves, through an act of sacred simulation, by keeping the names of the docks and transfer facilities that they replaced in the preserve of the Monument. The Edge, built from North 5th to North 7th Streets, on top of the old Cross Harbor Railroad is another condo tower, that did have the decency not to rob the name of the industry it replaced. It’s name is strictly here and now – trendy, romantic, hip. One of the Edge’s penthouses was recently flipped for 3 million tomatoes, delighting the investing gentry of gentle birth, confirming they had done the right thing. And today the right thing is money.

Unfortunately for the native population it is estimated that each $100,000 increase in property valuation requires the displacement of one thousand aborigines. It is also said it would take 2,000 aborigines to equal the hipness of one Newtowner.

THE EIGHTIES

Before the art of success, back when all the pretty ruins weren’t quite that, the place in its wildest was a creepy freak zone. A typical wilderness experience I had was, while scoping a view of the city in one of the wrecked buildings, I became aware of a presence. Looking way up toward the ceiling and behind me I saw a man in rags silently perched in some iron trusses. He had been there the whole time, maybe the whole day. How he got up there I don’t know, but, he, like an unconcerned bird, perched motionless, appeared dead. Sightings like this East River Horned Owl were quite common, as there was more fauna than one would expect in a wasteland, but often remained unrecorded, as my first reaction was to get out of here…

Risk is always an element in the back country experience, and it’s presence signals low simulation levels.

The usual things that would go on at an illegal park – partying (the serious kind), swimming in the East River, an occasional murder or dumped body, mob hits, scrapping metals, dumping and picture taking, not to mention, poor immigrants sunbathing on the piers (celebrating the Polish tradition of stripping down to white underwear and girdles), prostitutes, a prostitute killer, and, of course, camera people looking for that city view or abundant crumpled industry.

Bridge – Blue Collar Painter. The Monument, many years prior to the Hipster Putsch, had long attracted actual blue-collar artists who depicted its sublime nature. Notice the head and ear protection which became mandatory after the famous painter, Jean-Baptiste Ligero, who emerged from the LES street art scene, died. Ligero, who lost most of his hearing from the years he spent in the subways making art, was killed when a train he didn’t hear collided, uh, or, was it a hair-on overdose…

Today Ligeros sell for many millions and his fame has attracted a whole new generation of artists who arrive in Williamsburg to have it all, but not wait. They want it now, while they are young and can enjoy it, and, unlike artists of this past, who could be blue-collar themselves, or lower class, today’s artists don’t exactly arrive destitute, on the midnight train, or had to begin at the bottom. (only to find it better)

But it wasn’t like i was going to run into the likes of what we know today as the ruins and exploration pack. I did meet serious photographers though – as in distressed. I mean I saw skels with Hasselblads. Today, of course, it’s more art-lite, as they say – brilliant, fantastic and, of course, fun, in the art colony sense, but back then many did art in this town in that old outdated starving kind of way, and it was all about production. That was contextual to Williamsburg because nobody had nothing except work and the neighborhood.

The wilderness zones with no fencing or security, were a land of illegal and free expression, as was the entire Brooklyn and New York sides of the Monument, including the bridge itself, which was so free one could reach out and touch the red birds or check for the daily sullage or art vandalism which every part of the bridge was subject to, making it a center of Native arts, particularly pictographs. (The Conservancy has always condemned pictograph damage to great living structures. Other failed censures concerning skateboarding’s over-valuation, punk music after punk music, flash mobs and underwear day have been equally ignored).

Am I real upset about the demise of the industrial waterfront? Considering it really just went to Jersey, that’s a big consideration, and I would eventually bang out a ten year documentation of industry called, JERSEY RUN (1995-2006). I just had to travel five miles west for grit. But with regards to being upset about industry’s decline at home, what replaced it is upsetting. That’s why the Conservancy’s exile from Williamsburg was necessary.

OUR SLUM, MY HOME

In the time before the election of the Great Father and the coming of the Long Knives, there was plenty freedom. We were self-governing and our own Dog Soldiers kept the peace, as my particular block was affiliated with the Bonnano tribe. We were artless, so for a reality artist, with an appreciation for the freedoms and substance of the blue collar trail, there couldn’t be a better place not to take pictures – it wasn’t disappearing and who the hell would want to move here, anyways? Most importantly, we were free and not cowards.

The first two blocks in from the waterfront were beat up, but the rest of the neighborhood remained vital, utterly in tact and filled with vespo, the neighborhood gold. There wasn’t anything broke. Waterfront ruins were the graphic pretext to opening up the entire neighborhood for the development that would never improve our lives. The discovery of the golden views that were always there on the waterfront meant no treaty, no sacred place would be honored in the face of the coming hipness. That’s why Natives had a tendency not to see the New York skyline for fear it would look back and see opportunity, not to mention we were, of course, too stupid to appreciate it.

Social club on Leonard St.

The Greenpoint Holders which also featured a little league ballpark. The tanks were purposely imploded in July, 2001, and is still an industrial property associated with natural gas

From, Only the Dead Know Brooklyn: “I was bawn in Williamsboig,” he says. “An’ I can tell you t’ings about dis town you neveh hoid of…”

That’s kinda why I take pictures.

No ruins project, it’s postcards from home, from a time when to be dislodged wasn’t conceivable (we were, after all, primitive, stupid), but we all knew it was imminent. It’s just that who’d a thunk it would take the form of hipness, which formerly delineated a non-commercial, non-mainstream, ethos-oriented group, small in number and in the know. There also use to be a place called the underground, where even substantive hipness might be transcended.

Hear me, i lived through the Blue Collar Holocaust, in the end it would be hipsters “remaking” my home that finally killed it not its economic challenges as a blue collar neighborhood. In a ten year battle between leave and stay, what do i have that is left? I have much experience that i’d like to forget – of those who came and remade. One observation is, they equate art with success. BEDT would be the beachhead and ground zero for the invasion of the professionally hip ones. But way before this, the alive and dead industry on the waterfront was close, so I shot it casually, as a flaneur, and, for not much reason beyond gathering funereal snapshots of home for nobody. Of the many books I’ve done on forgotten places, you’ll never find one with strictly ruins, like WNM. By doing so, the land appears as if hit in one fell swoop, but not evolving in an actual living way in its alleged demise. My point: the Williamsburg waterfront was half in ruin at one time, and the rest of Williamsburg and Greenpoint was not in ruin. It was old, worn, and alive in the best sense. To fool with that mix in all its historical veracity, in one of the lasting pockets of sincerity, could only mean that, as in art, real estate and ego, in certain cities, would no longer be fettered to any sort of relativity. And with the sky as a limit all types of goofy shit happens.

Ruins implies the shooter just showed up, but abandoned means the shooter had been here before. The Ruin hounds, are tied to representations they have consumed about what they never experienced. Experiencing the actual subject over time, and isolating shooting to that, the regressive progression of abandonment can prove its source and evolution.

The waterfront was messed up, but not where we lived. Of course, nothing lasts, it’s just that nothing lasts shorter now than ever before. More New Yorkers say that the city has grown unrecognizable to them. And as it turned out the notorious Kodachrome 25 in my cheap camera was a lot more archival than a marine transfer station in Brooklyn. It too was predictive of more oncoming extirpation, literally, as all Kodachrome became completely extinct in 2010.

I’ve been shooting the Rust Belt as it stretched from Brooklyn to Chicago to Butte, since the 70s, when Kodachrome was state-of-the-art, thus i have specialized in the depiction of last things. Who would want their beloved home in that group? So it was a different type of shooting, reluctant, a bit necessary, but not really done as rigorously as my larger body of disappearing urban industrial America. WNM was simply built around neighborhood hikes, and my every day routine of walking to the LES in New York and back.

Williamsburgh surprisingly remained a blue collar stronghold into 2000. It’s character was very strong. It, of course, resisted, some nearly to the death. And unlike the deletion of, let’s say, Penn Station, what happened in Williamsburgh is purposely missed by the cultured new owners. The displaced, although their voices were completely authentic, and huge in number, were/are never heard. A history wiped clean, including it’s last chapter, We Don’t Want This.

WNM was buried as a matter of course. It wouldn’t have a place in its time and when times changed i feared it would be interpreted as a call for additional awesome reinvention or, become mixed up in the ruins fetish. It was unearthed by a special team of archeologists from Columbia University in 2013 looking for artifacts from an authentic time, otherwise it would have remained in a landfill.

Thankfully the massacres are receding as the gentrifuckation is complete. There is no danger of robbed intentions, since the thievery is now total. Thus these pictures have become postcards, filled with the sense of place/displace.

RUINS THROUGH TIME

WNM was neither titillating nor a fetish in its time, but if WNM survived it would have been. For some reason, these kind of images got connected to the history of art exclusively, instead of the history of mistakes, or just plain history. Ideas whose origin is solely in one’s head, are not like ideas that come from contact with things outside the head. See what you believe, or believe what you see, is another way of saying it. In its time WNM would be considered a cheap shot, an easy shot, this stuff was everywhere for a long time and people were (made) sick of its depiction back then. Now photographers want to kick themselves in the ass for taking for granted, something, they thought was an established feature of living in big bad New York and Brooklyn or the Rust Belt. Now that it’s gone people want it back, but I guess only in pictures, although I’d trade pictures for the gone New York any day.

WNM is about the time it was shot, the birth of the Rust Belt. Any moron knows there was far more industrial-era ruins with much more equipment in tact, then what came after the recessions 2001 and 2007. The level of destruction was on a far greater scale. There were only a few monument shooters back then (i’m being kind), unlike the hoards of patina hounds set loose on an ever dwindling source of abandonment the last ten years, pinning Detroit as the easy symbol or lone symbol, when hundreds of towns and cities are in the same descent.

WNM proves that the porn ruins debate is part of the whole fetish that this sort of thing becomes. In the past the end of industry may have been artfully serialized or socialized in documentary form, but it wasn’t gelded through tourism. Maybe a few transcend these limits, but most still don’t know what they are specifically talking about, or shooting, beyond “the great tradition of ruins in art.” since that’s all that’s required.

Check the cover of the book, DETROIT DISASSEMBLED, from 2010, possibly the highest level of ruins photography produced by a master, who goes back years before the rise of ruins as one of the dominant forms of documentary/art. It features a rolling mill hall ruin at Ford’s old Rouge steel mill on its cover. Ford sold the Rouge steel mill to a Russian firm, Severstal, in 2004, which, in fact, revitalized it to the tune of 1.5 billion dollars and they built the first new blast furnace in America since 1968. Ford could only sell the mill with the union’s approval and they picked Severstal who kept their promise and did a lot more than save the place. It became Severstal’s flagship American mill. It’s still running and now owned by American AK Steel. State of the art, it’s highly profitable when commodity prices rise, and i own shares.Next door Ford’s most sophisticated assembly plant bangs out vehicles like the F-series pickup trucks.The Rouge still churns out 150s, the most popular truck around. It also uses more lightweight hight-tech aluminum than any other vehicle in the world, while buying Severstal’s specialty auto steel next door.

A subsidiary boo boo, the mill does not operate in Detroit, but Dearborn. Large operational industries always have sections that die off as new technology replaces it, and that’s what ruins inside operational industry actually represent.

Severstal Steel, Blast Furnace “B” – River Rouge Plant Dearborn Michigan, 2004. Severstal built the first newblast furnace in America since 1968, in this Dearborn plant, four years after this picture was taken. It replaced old blast furnace “C” which literally blew up during the spike in steel prices of 2006.

,

,

Situated within the city of Detroit, the Zug Island Plant of US Steel continues to make steel – molten slag lights up ore and coal hoppers, in this 2004 picture. Unfortunately the mill was shutdown in 2020, although the American steel market is now booming. The ruins’ hounds ignore this situation constantly in service of the fetish. RealStill always shows the ruins and the operational things still left.

After all, Detroit still has 700,000 souls still working and living in the city.

All else is located conceptually, that is, not dynamically embedded in being. Art’s location in the cerebral has grown to define it. That’s fine and perfectly obvious, but the Institute is thinking about the way broader perceptions are manufactured by concepts that allow hipsters and politicians to react accordingly. Thus the Institute has always found itself in the peculiar situation of being too documentary for art and too art for documentary. Criticized for its pursuit of truth and denial of change, at least of the gentrified kind, obscures the fact that the Institute advocates truth as a debunking, and promotes history as experience opposed to baloney.

Sometimes things are abandoned merely from being jettisoned as the company builds newer plants, around old ones or in other places, unseen, which stands to reason. And, sometimes, as in Williamsburg, it is cruelly the end.

Is the Institute demanding accuracy in art photography? Hardly. But, its absence can only highlight the beauty of those rare moments when the two come together. Accuracy just happens to be a consideration, or a lost art or one of many art specialties, albeit a distant one. It’s hard to ignore if you’re inside the subject, and this is my problem alone.

Contrary to the present ideology ruins during the time of WNM weren’t pretty, but pretty threatening. They weren’t cool and certainly using it as the pretext to luxeing out the poor, whose richness was their neighborhood, is an abhorrent and dirty way to enter Brooklyn, which, of course, is no longer the LAST EXIT it was, particularly where I lived. It is exceedingly well-known as Hipster Heaven, and, really not taken very seriously, except by the Times, who now, at least, sees Gentrifuckation as more of a problem, then a party, and, curiously, particularly in the tech regions out west.

As late as the early nineties every Sunday the same Times business section would recap the nation’s economy based on things like the amount of lumber or steel produced, cars made, etc., since the economy was still based on manufacturing. Today the health of the economy is gauged by real estate prices, even dubious “products” like derivatives, hedging, betting, putting, shorting, not to mention, playing remarkable financial instruments like credit default swaps. It’s hard to understand the “products” of banks or casinos as having substance, but then, the introverted thought architect dwells behind the neighborhood that is taken over by extroverted technicians.

Main Entrance to headquarters of BEDT – photographs of abandonment, what is now called ruins, all look the same age no matter the specific era or time. if experienced while alive, it’s abandoned, but with no real knowledge of its existence, it must appear disembodied, or, as a ruin, not as an ongoing 40 year decline effecting hundreds of towns and cities with the same history.

In the realm of institutional thinking, history can be selective.

Look at the work of Mr. Charles Cushman who photographed, in color, industrial and working-class neighborhoods and streets, going back to the thirties. You’ll see his old homes, slums and industries, looking not much different from anything shot since then and today.

In the eighties it was still called the waterfront, but from elsewhere it was called ruined. The moment these places flip, they, are, essentially still what they always were. What changes is the idea or concept of, not what they are or were – that’s just ignored. in favor of incorporating them in the reivention sense.

McCarren Park Pool in 1986, and twenty years later in 2006, before it became an ironic wildly popular concert venue, prior to its complete rehab and reopening in 2009. Still pretty much the same as in 1986, but with more flora, and the arrival of condo towers such as the one being built in the right hand corner. It also flipped from abandoned pool to concert venue before its own rehab. Flipping the pool conceptually into something entirely unintended only fostered more concepts such as C.S.B. – the concept of Continual Spring Break, the guiding force for the new ones, and an embarrassment for the Institute, so much so, it dissolved.

Reconnect with this: 1.) Back in the seventies and eighties, the powers that fed things like the art world were still based in industry even into the early nineties and they didn’t appreciate seeing industry as it was in the beginning of its long fall. 2.) The Greatest Generation, at least the most powerful, had already exited the cities for the suburbs and didn’t care to see depictions of American cities that now looked like the bombed cites of WWII, 3.) It was the very height of the cliched, to shoot such obvious ubiquitous decay in art and journalism, the classic cheap shot. That’s how much of it was around. At the least, it’s a fitting rationalization as to why my work was ignored.

After race riots, white flight and finally economic collapse, by 1978 all cities with ties to industry had vast swaths of ruin, and, for those who never fled, that’s where we lived – amongst ruins, but not in them. It was prophesied that, in the years after Soho, once the ruins were “fixed,” so too would the native population be fixed, as in class fixing. So we were leary.

Overall, shooting WNM wasn’t something I was particularly excited or motivated about. I’ve always enjoyed live and operational industry better, a lot better, and i’ve got more than enough of both the dead and alive in my archive. More importantly, it’s always been disconcerting shooting too close to your home, let alone when the subject becomes its inevitable loss. Williamsburg was covered in factories and where I was from, west of the BQE, the residences were squeezed amongst manufacturing and warehousing of every kind. Our block was mostly dominated by a single large factory that mingled with just ten small eight and three flat wooden tenements (originally a shoe factory, it was both an operational garment and mattress factory when it shut in 2005 for its coming recontextualizating). Curiously the whole neighborhood is zoned for six stories and the new condo on this old factory site is 17 stories, a miracle celebrated twice yearly both on All Soul-less Day and the Feast of the Immaculate Variance.

Safety, the ultimate concern, particularly since 9/11, for New Yorkers meant the serious elimination of danger, without which, places like the WNM are just movie sets. Like 42nd Street in New York in 1993, safety was the key in attracting corporate cooperation. The final commercial use for the waterfront was its use as a background for every rap video, and feature film simulation about every Irish, Italian, Black or Fake gangster in New York. The dangerous bad neighborhood was so over-represented that it began to defuse itself. That’s how a lot of people from all over the world who never set foot in Brooklyn got to know the place before they would take it over – beckoning on cable, or, more literally, in the Times, or television series and movies that depict the lives of hipsters in the city of New York.

Later, by 2005, the movie set would further evolve into the art ruins set. Here, for instance, a graduate student from Columbia (who probably just moved to now safe Brooklyn) could comfortably pose nude or in underwear, in the ruins of the Revere Sugar refinery down in the Red Hook Reserve, as I saw published here in New York. Proving not just the north Brooklyn waterfront, but anywhere industry lied dormant could become hipster fodder. The softening of minds from contextual and critical thinking to the simplicities of self-enjoyment, erotica in the ruins or just just plain coolness meant the simulated Brooklyn was firmly rooted and found some of its greatest achievements here. Thankfully this

WNM was done many years before the embedding of the Williamsburg waterfront in the minds of so many who knew absolutely nothing about it. That’s far more weird – creepier than an East River horned owl at twilight on the waterfront back in the “bad” old days.

We don’t need to explore, in what’s home, being perhaps not “new to this, but true to this” and knowing this is all forgotten, because the third generation copy speaks louder and schmoozes better than the source in its backward originality.

What BEDT became was a memorial to extinction inside the old Brooklyn badlands. What we first thought was the extinction of good waterfront jobs, we would eventually see as quaint, compared to the deletion of all working class Greenpoint and Williamsburg and our remarkable way of life, and not from economic decline, but development.

GENTRIFUCKATION

Before commencing with this section I recognize the Awesome Mandate of Reinvention. The subject of class is to be entirely ignored. Of course, discourse on race, sexual orientation or civil rights is accepted and encouraged. Class is not part of any discourse and, in itself, is nothing more than the bad socialism, we left behind years ago. It most certainly has nothing at all to do with gentrifuckation or displacing the working-class by a more creative one.

With even the mildest forms of critical thinking suspended in the boom years of the nineties, the plague of hipness commenced, and is complete. The colony, its mixture of real estate, art and entertainment, manifested in the wildly popular art lifestyle movement that found its home here, moved out to Bushwick, and now Ridgewood Queens whose progress as an art colony is a bit hung up on the “Queens-is-not-cool” determination made even before the arrival of the next hip member of the creative class. Zip code envy over the “eleven two eleven” has resulted in yet higher prices to fit the art of the deal in Williamsburg. Nonsensical, like the words, social media, that zip codes are hip, cool status markers today. Just more of the the nominal or simulated replacing of the source material, and once a source is squashed, nothing is relative anymore, like the prices of New York real estate and art.

The arty party hardy here in this New York City. Certainly not all the brains are pickled in fun, it’s just what I saw empirically every day and every night as artist code in Williamsburg/Greenpoint, which had become a recreation place, as in reinvention, or extension of college life – parties, roommates, sleepovers, drinking, drugging, all to the tune of mom and dad’s money. I think they considered themselves artists, who, of course, by nature are not tied to any, or even the smallest, urban courtesy, because, well, they’re crazy. Now that’s an embarrassing neighborhood. Around 2001 we began to refer to ourselves as townies, as we became the proudly separate minority.

Art colonization is a phenomenon and the occupation of entire neighborhoods by its practitioners, by now, has become a science (tech) and an art after bursting out of Manhattan over 30 years ago. And the demand is there as many thousands pour out of the schools with an art or tech specialty and all the skills it takes to live in a high-priced art neighborhood, and working all those jobs in the business of art and entertainment that booms here like Wall Street and property values.

I don’t know if any of you saw the Times piece, written by a Lucien Freud scholar, about how, near his death, the artist finally admitted to, secretly longing to live in Bushwick, after missing trending Williamsburg. We presume today’s bona fide artists want to live together in marriage and as neighbors, as well as work together, completing a full artist lifestyle. And, of course, you don’t have to be from Brooklyn to name your kid, Brooklyn. It doesn’t even help.

Wildlife within the Monument provided opportunities primarily for fishing and birding, reflecting its maritime roots. Some rare fauna like the Wingless Horned Owl and the girdled Polish sunbather could be found here as well.

There were the more common urban mammals, like the two-legged skell. or Rattus Norvegicus, the non-native invasive rodent that first came to the harbor in European ships. Such colonizing rodents did not plague the neighborhood very much in the, uh, “bad old days” nor did crime or lack of culture, as expressed retrospectively in the Great Hipster Neighborhood Fuck Fantasy.

Although our homes were, by and large, original Brooklyn no-law tenements, they were vermin-free, much like our streets, that were so low on crime, night noise and irony, we never even thought about it.

We saw the birth of the Hipster Fairy Tales – our colonization would result in a reinvented better quality of life. That never occurred, since we already had life’s best qualities to begin with, and you don’t reinvent a source. You don’t destroy it either, unless you’re the ultimate in self-involvement, and that would be the selfie spawn of the Me generation.

These three juveniles are the last members of a colony that had nested throughout my apartment on Union Ave. in the summer of 2008.

No one wants to look at rats, even in pictures, credit me for leaving the hundreds of mammalian excreta pellets undocumented, thereby furthering the lost proof about this Gentrifuckation, which, like deindustrialization, is unstoppable, just a hell of a lot quicker. And, like a lot of things throughout history, that, during their reign, blotted truth with overwhelming desire, anyone displaced, loses, but does have an undeniable experience of it, making its memory indisputable. And that is a memory of injustice.The home colony was housed in the cellar of the well-known hipster bar, the Royal Oak, and they dined there on the ingredients for the fifteen dollar watered down fufu drinks. My particular home, 2nd floor in the building next door, merely provided nesting spots that hey found by travelling through all the holes and unrepaired damage during the years of Perpetual Renovations, that stayed unrepaired, by order of the Master. The hunt lasted months, followed by the plague of rat ticks and fleas that ultimately would pursue the only living mammal left in the house.

We never had a rats like this in the “bad days” or even cockroaches, in our apartments where not one moment of maintenance had been performed in the years i spent there, taking care of the place myself – and that’s not a complaint, but trade-off.

It can only be coincidental, that a person paying five hundred dollars a month rent in the heart of the 2008 trendopolis would develop a rat problem. Union Ave. at McCarren Park is one of the most expensive and luxurious places in the world. Surely this is staged and improperly dated. And if it is staged, and improperly dated, then it would be the first time in 40 years of photography that i created a real work of art, at least in these times.

It begs the question, why rats now? The Forgotten know, but are lost and dumb.

I guess that’s why artists’ colonies, particularly the pretentiously named millennial ones, like hillbillies, the klan and nazis are uniformly disrespected in a completely socially acceptable way by everyone but, perhaps, themselves – Hillbillies being the exception. They can revel in their own stereotypes, and flip them like Blacks have done on the n-word., into profitable entertainment subjects in music, cable shows and even literature like Hillbilly Elegy, by the Hillbilly Phoney, who wrote the book.

Williamsburg, in its blue collar century and a half, was the rent stabilized stronghold that held out way longer than expected. So entrenched was its stubborn indigenous working class mentality, it hung on. Even into the late nineties. one could still live the life of a full-blooded coujine or any other kind of blue collar warrior, right up until 2001. Our village was self sufficient as were the camps of neighboring tribes and we were all very happy. Simply stated, it was an iron-willed home.

In 1986 Brooklyn was less than 100 years a part of New York City. The Williamsburg industry and its North and South side enclaves were cousins to the LES. Both had the right amount of blight and hyper-patina for the times, keeping rents low, spirits up. For a while the Monument served its purpose, frightening away people with money looking for a good place to invest or live. Our tribe’s secret had always been, it’s the best place to live in all of NYC, at least the best location. Eventually repeated feigning, blunted fear, it was hip. And the washichu came, replacing their saga of suburban angst as the only one for poor old Brooklyn.

Without its history and its edge (risk), it’s just another embarrassing place, and, that’s what happened. It’s just another unoriginal fancy place of pretense. What’s hip today isn’t even an illusion of substance. After being forced to witness the whole debacle, I’d say, today what’s hip is comfort in the city, constant cultural nourishment and success, not reality.

By stocking the New Place with all the quirky amenities one can only get on a vacation, making it new, and broken from its past, becoming, i mean, remaking itself into Williamsburg, the tourist destination. Apparently that’s what many people want these days. Others, we gotta work.

We knew them as the fat takers when they arrived. But they called themselves “foodies.” How could we fight a people who possessed no meaning of their own, how do you fight an enemy with no memory or history? They called their power, “my parents’ money” and it protected them. The washichu are crazy, you know, and love the safety of the simulation, over the actual or the real.

The Antiquities Act, and its major legislation, rent stabilization, held to the notion of place. Stabilization preserved and encouraged the tight knit neighborhood, which can only evolve in a relatively unchanging locale over time, enough to generate a completely local culture and an extremely high degree of nativity. Reasonable rent is the only way the working class can survive and develop a culture, without it an established people will vanish at the hands of the creative class, disappearing through forced displacement that destroys these generationally settled folks. What constant little blight there was kept the rents down, the indigenes rising, and the developers uninterested, at least until the blight virtualized as ruins, and began to signal opportunity and the beginning of the end of our world in north Brooklyn.

View out my front window a long time ago. After the towers fell, and the internet rose, so to, did the ruins fetish, concentrating on destruction alone. By the time the Towers fell, RealStill had been shooting disappearing America for decades, develpoing a sense not just of loss, but being there and documenting something operational and before its fall, and proceeding, then, to document is fall and demise.

A billion and a half bucks finally fixed the sewage smell, the pool next to my home, closed since 1983, got revamped, reopened. These are some of the things we begged for years to get done. Once it finally happened, for natives, it became a very bad sign, for it had been prophesied, that, even those who had survived gentrifuckation to this point, would still suffer removal once the pollution was gone and recreation was adequately provided. This only attracted more affluence, while multiplying the pressures (harassment) on natives. The prediction, of course, came true.

Mccarren Park Pool, 1986.

Mccarren Park Pool, 1986.

Mccarren Park Pool, 1986.

Mccarren Park Pool, Ticket Booth, 2005.

Mccarren Park Pool, 2005. Notice the condo being built in the upper right. 2005 was the year of the rezoning and tax breaks favoring luxury housing.

Mccarren Park Pool, 2005.

McCarren Park Pool, 1986 – Clearly the era of organic descent (1978-2006) was on full display at our pool. Closed in 1983, rehabbed and reopened in 2007 and left untouched as a monument to neighborhood stability and, for a long time, an insurance policy against high rents. An industrial preserve from the oily days after 1850, up until 2006 when the zoning went from preservation by virtue of poverty to change by the sin of greed.

The Freebie Eviction Decree, celebrated every year during Pile Driver Days, nullified the length of residency and/or senior status rights from the Stabilization Treaty within the Antiquities Act. It was the final official recognition of the power of the Hipster Putsch. From here on in recalcitrant natives would silently disappear from their blocks, in the cattle cars moving east on the “L” line, with the exception of a dog soldier of exceptional character who would move north into the Black Hills of the Bronx.

Da Bronx, just like, Williamsburg, at one time, it’s all perception. Ya just gotta flip it. At the moment these places become inviting to gentrifiers, it’s still the same place, in reality it always was, but perception is everything in reinvention, flipping or it’s newest incarnation – disrupting.

The “narrative-mongers” and media, print and art professionals are masters of perception, and, perception, itself, as part of the stupendous growth of individual subjectivity, is vital, particularly with falsehoods and obscuring lack of talent or substantiality itself.

Karmic capitalism has taken everything for its own including most all of what previously had excluded itself from commercialism – the hip, the cool and karma, to boot. What’s next, soul itself? Oh right, the Kia Soul Absorption and blending with no root, consumption, and, money as the fertilizer, meant the swells would flood the place. Their loud disrespectful habits helped drown out the sound of the then majority of hearts breaking all around them. We all knew the drill. The chances of keeping Williamsburg and Greenpoint in any of its original context, were always about the same as opening up Fifth Ave. to section 8 housing. It would be displacement or death – fulfilling the prediction that our people would win every battle and lose the entire war.

The ruins crowd neutered what WNM symbolized – class distinction and the ongoing Blue Collar Holocaust. And, in the year of the Gilded Gelded, the Greenpoint/Williamsburg Contextual Rezoning of 2005, insured complete loss of memory and any historic connection. The drumming of the Pile Hammers and the loud music of the Arty Party People would drown any authentic neighborhood voice, as well as, drive any critic of it, literally, crazy.

Using a high-pitched sonorous and nasal voice, say, “This rezoning will ensure that the reuse of this priceless but long derelict waterfront will be for the purposes of housing and recreation and not for such inappropriate uses as waste transfer stations and power plants,” Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg told reporters at a late afternoon news conference to announce the contextual zoning of Greenpoint and Williamsburg. These are exemplary purposes for a somewhat ruined waterfront, but the rest of the neighborhoods were just fine, nevertheless, they went the route of the waterfront.A single railroad flat in an old no-law wooden eight flat tenement, the little primitive traditional home of the poor tribes of Brooklyn for 150 years, now can fetch a half million easy. Irony couldn’t even be pronounced, let alone understood here, thus we dumb asses couldn’t appreciate our own demise as a defeated class, too broke to invest in its own boom times. For us it was not entertaining in any way shape or form, it was a party of sadness. It was real degrading and real painful. Experiencing displacement like this it’s easy to testify that it is injustice on a jumbo scale. The ones who are victim to it, are known for their friends and family ties. That’s real local, not global. And it is only the local that is entirely real.

Cono’s Pizza Shop – Jimmy V. (seated) was born in an apartment that occupied the shop back in 1910, Jimmy lived his entire life in the building and died there in 2002. He was in the Guiness Book of records – as a strong man who could pull a military half-track with his teeth, and as a champion ballroom dancer. Jimmy was much more of an interesting person that any peerfromance artist that ever lived in Brooklyn.

Contextual zoning, whatever that means, and a decrepit waterfront were a pretext for supplanting a zip code colony of gifted creators, if not downright geniuses, in a place where a perfectly opposite character reigned for 150 years. Embedded in the industry, is how we lived. To take away the industry was like handling the “Indian Problem” through buffalo slaughter. Preserve the character? How do you preserve by annihilation? Adaptive reuse zones, incubators to hatch ideas on the blank slate of blue collar Brooklyn, landing zones for the insufferably cool spawn of the baby boomers, nothing contextual or connected and nothing original in the heartless flipping of Williamsburg from slum to affluence. We had seen it all before. After all we knew of the transformation of the Soho lands across the river, and all the others that followed. We were here. We see and hear as well as anyone can, but we can’t speak or mediate.The 2005 rezoning of 175 blocks of Williamsburg and Greenpoint from heavy industry to residential, celebrated every year in the Feast of the Immaculate Variance, is the official end of the WNM and the beginning of the end of the forced marches out of our homes and into Queens, with the exception of that one holdout who pushed north into the Black Hills of the Bronx.

Rooms with a view preferably on a waterway, generate quick large profits as did the docks and piers in their day. Owners in condo towers, their windows a kind of high def screen on New York, can now look down and feel exalted, comfortable about their investment in their neighborhood and the sheer loft of it all, the god-like view, truly exalted.

Industrial production and its transportation system didn’t evolve into the tax-abated view and shopping. It was trounced, then what was left was kicked out. The view produces wealth and is most coveted. Tax abated luxury dwellings, like tax breaks to lure film production, couldn’t be socialism or corporate welfare, they are incentives, while something like rent stabilization is the regressive and bad socialism we are progressing out of as city. I learned that the hard way.

A very polite and filtered version about how basically everyone who is from their neighborhoods feels when their turn arrives to be gentrified.

It’s not a secret, we’re simply muted outside ourselves and our little neighborhood papers, but this is basically how the entire neighborhood felt.

A place of hard, dirty, physical toil has finally became the leisure and party destination which was first envisioned in 1800. The 150 year industrial run, now just a detour along the way to the straight line profits that an upscale entertainment inclined Williamsburg could generate, is more than over and gone, it’s forgotten, especially the fable of life within its industrial setting.

Gentrifuckation is reinvention – into its mirror opposite. Amenities, one only experienced at resorts, replaced a dirty sublime authenticity that required joyful struggle and, coincidentally, built character, and produced, nuthin but soul. You know, the kind of exotic stuff tourists buy into so much that it eventually disappears from its original “coolness”destroyed by the admirers’ addictions to culture, comfort and the inconsiderations associated with colonialism.

END

And let’s face it, The people – professionals and their kids, in the media for instance, the very ones who benefit from or institute what becomes displacement, could help the victims of gentrifuckation. All the other professionals whose job it isn’t, well, their heads are in the feed bags, but let’s face it, they all don’t give a shit in the truest way – it’s non-existent to them, but not all those ruins.

Ruins photography is part of a gentrifying mentality. If you don’t believe me, that’s fine. No one could expect a person to accumulate a life of proof and authenticity, let alone go beyond presumptions (these days), thus, i’m definitely “too good to be true.” Things occur too quickly now, or, as it has been famously said, “The introverted thought architect dwells, until eviction, in the neighborhood taken over by extroverted ahistorical technicians.”

Nevertheless the Institute has been involved in this ruining for 42 years, and ruins implies the shooter just showed up, and not be there for the whole demise, resulting in abandonment, but not ruins, where there is no experiential connection, only the representations and perceptions that have come before, as disembodied signifiers unto themselves.

Before redevelopment things were left pretty much in their own state of organic descent, like in the picture sequence below:

Prior to a jacked up urban redevelopment powered by service workers, cities were allowed to vanish in their own undisturbed organic descent to nothingness.

We don’t wait the return of the buffalo. We never believed in the promises of affordable housing, or something termed contextual rezoning, and not the actual contextual liquidation or creative destruction that predictively occurred. History bears this out, confirming the absurd promises the city made in cahoots with developers. None of this matters. I wouldn’t live there if they paid me. No rez Indian, i will never live in a neighborhood that has any chance to flip arty and/or upscale again. My death song to the Newtowners is, “You Can Have It.”

Lost in your ironic culture, you can’t get the Big One – the fact that for a very long time before you showed up, Brooklyn wasn’t “cool” and that’s what made it so, and that’s to use the worn out lame and misplaced terminology that tv news anchors, morning show hosts, their children, and, of course, hipsters use today.

It took a 150 year industrial interlude for the waterfront neighborhood to come back as it was intended, at least, in 1800 by real estate interests. The one thing Newtowners share with all the immigrants before them, is the huddling together for safety and to retain their full culture and customs. I think, even the hipsters know, that, in most New York outer borough neighborhoods, they would get their asses kicked for how they act, if not arrested. In fact the Hipster Flip links them with the original developers of Williamsburg who envisioned only a suburban leisure spot for well-off folks.

For all its time Brooklyn was defined by its working-class, all the way down to the way it talked. The rich now know Brooklyn in their way, having bought the rights to the name. The Boomers’ spawn, continue to put the party in art, or, at least, the art of colonization and their other dominant skills – conceptualism and imagining things as your selfie empire.

Brooklyn was a place where the anonymous might become famous. There was Williamsburg and Joseph Bonnano or Greenpoint and Mae West. A lot of stuff came out of these neighborhoods too, the Monitor, the Iwo Jima Memorial, kerosene, sugar, iron, and exemplary fiction. And now the famous come here like they did back in 1840, only this time they’re staying, or, at least, buying into it as a permanent vacation.

Psychogeography will live on, particularly after the moment of its realization was lost in Brooklyn. In my part of the Bronx, in my lifetime, i guarantee there will be no gentrifuckation. There are other pockets of sincerity as well. They dwindle, maybe, but I will always have work. Our philosophy doesn’t change, using the Domino Sugar mill on Kent Ave. as one example, we say, unless it’s a functioning sugar mill, tear it down. And, if it ain’t broke don’t break it.

WNM can be viewed as a cry for redevelopment, or just a crying shame, depending on who does the viewing. Intent is a futile pursuit more than ever, and so is the attempt to stifle it, even by consumption. I own these shots because i made these shots, but i also know the territory and lived it. Your suppose to cringe a bit at all the pretty ruins, not get aroused by them or their potential as real estate. If I shoot them in a sublime manner, obviously i’m creating discomfort and attraction simultaneously, but, don’t forget it’s also because it’s my beloved home. Of course this was 30 years ago, when ruins weren’t the fetish they became, but stood as a sublime reminder of a mistake concerning industry, the lower classes and the horror of not making things, especially close to home. And i’m talking about the Industrial Revolution, not reinvention or artisanal cupcakes and two dollar bagels.

Later I would come to realize the Monument’s weird creepiness might have been an advisory too. After all, what’s more weird and creepy than your displacement through gentrifuckation by hipsters? Only Martians, i presume.The first phase of the Blue Collar Holocaust going back to the late 70s, what became known as deindustrialization, was, of course, job destruction. After surviving that, and years later, the final epic demise – the seizing of homes by ignoring both legal pacts and basic rights would result in classic displacement according to class, I mean, our own lack of ambitions and foresight in real estate investing. The great founding myth of New York – the purchase of Manhattan for “$26.00 in beads in trinkets” – explains this quite well, and, of course, the rest is history, washichu-style.

Today’s Inwood Hill Park commemorates the Reckgawawang Indians’ “sale” of Manhattan to Peter Minuit with this plaque. It’s first three words are its most vital – “according to legend…”

The WMN was an authentic monument to the death of manufacturing and the blue collar world in north Brooklyn. It stood for 23 years and during this time its message was don’t make me over. The Monument, and this book are equally anti-gentrifuckation the same way something like LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MEN was anti-celebrity.

Was it otherworldly? I don’t know what to say, many of us called it home. I’ll tell you what is otherworldly, the epicenter of hipster-luxe that this place has become. I doubt if Auschwitz will ever sugarcoat or hide what went on there. “Unrepurposed” as they might say on the Brooklyn waterfront today. (Repurpose, “whoevevah hoid a such a thing?”)

At first the pictures of Williamsburg National Monument were just Kodachrome post cards meant for nothing, not part of my overall serious work on the same subject. Thirty years later I’ve come to see them as capturing a sense of being out of place in your own home, uh, but only in retrospect. There was no such thing as ruins photography back then (70s,80s, & 90s), and for us they’re just a buncha post cards of home that became gone.

Brooklyn ain’t New York, that’s for certain, but now it ain’t Brooklyn neither. Cleansing me, making me safer in the place that was always the safest neighborhood in Brooklyn, did nothing for me, besides our dog soldiers always saw to that. There are no advantages to living in an art colony, particularly if your attachment is to the world, not the world of representations. Maybe art should criticize itself in this town for sleeping too long with real estate, for being such a trick to such a whore. Artists have never been strangers to north Brooklyn before the creative throngs showed up, particularly the starving types trying to save money. They just never called the shots before, but were content with, if not, the inspiration of the artless, then the isolation it provided. I like Henry Miller’s description of the enclave called Fillmore Place in Williamsburg. His parents moved to 662 Driggs Ave. in 1896, across from this short street, in Williamsburg, a place where every block was its own world. In his novel, THE TROPIC OF CAPRICORN he described Filmore Place in Williamsburg as, “…the most enchanting street I have ever seen in all my life. It was the ideal street – for a boy, a lover, a maniac, a drunkard, a crook, a lecher, a thug, an astronomer, a musician, a poet, a tailor, a shoemaker, a politician.”

But it was a quieter time, less noise (lies)…

After closing times at the local factories, and on weekends, our neighborhood was quiet and peaceful. We had the good, hard, innocence of the working-class of an outstanding historical stronghold for the blue-collar world, its culture and its wages.

The gentrifying washichu love the diversity of the cities they’re not from. They really appreciate New York on the multi-ethnic level (the old New York), the capitol of which is now Queens. But, of course, they’d never live there. Apparently they don’t like diversity where they live in hip Brooklyn, which, prior to the their arrival had that original mixture of people, like Queens, to where the displaced natives of Williamsburg fled. (displaced artists usually move to a different Brooklyn neighborhood) That village of characters remained true even into the late 1990s, believe it or not. Fuchs’ SUMMER IN WILLIAMSBURG set in 1934, and, of course, Smith’s A TREE GROWS IN BROOKLYN, set in 1910, featured those same neighborhoods of characters who still kept evolving even during the end of their reign.

The ailanthus trees of New York, the tree of heaven so closely associated with Brooklyn, began to mysteriously die off starting in 1996. The tree, known for its hardiness, its ability, not just to survive, but to flourish with nothing, except a little dirt, is becoming extinct. Curiously the disappearance of the trees coincided with its death as a metaphor for Brooklyn, where it now takes a lot of dirt, more than anyone from the old Williamsburg could ever imagine, to take root in Brooklyn.

Speaking of dirt, real estate and art again, as well as, character, check out the Lenape who were around the Tristate for at least 100 centuries prior to the seafaring Europeans. Their creation myth is a beautiful take on Lenape history, their foundation in the Tristate as a tribal trust of klans. It fused art, history, law and land into their myth of creation, in contrast to the Eurocentric Manhattan creation myth of cutthroat real estate deals that began with the sale of Manhattan to the Dutch.

Ghettos are bad and conditions miserable. We had 25% of our city’s poop, pumped in and treated in open sedimentation farms, one of the top three oil/gas spills in American history that is ongoing, plus it’s underground, also, the greatest sewer gas of any red zone neighborhood, not to mention all the traditional industrial smokestack pollution. Until the mid nineties it was the go-to place for illegal dumping, often toxic. The list of ugly facts, endless. In typical blue collar mode. It was dealt with, and, through toughness, redeemed by joyful overcoming, that created the beautiful authentic neighborhood life, that is defined by its own limits, usually financial, and keeps us close to the earth we will return to, and not unlimited concepts, purely imaginary, that wealth and security allow.

We were never ignorant, just ignored, like the forgotten should be.

Slums are bad places and poverty is the worst. It’s a fact. It’s transcendence was the freedom, soul and occasional wonder, it gave us to manage it, make it work for us. It was, if not heaven, our Magic Kingdom and God help anyone who would fuck with it. Its blue collar ethos – not to be scared of doing hard, dirty, dangerous work, not being shamed into irony by the lived sincerity of our direct, to the point message, not being afraid to speak truth to morons or frustrated by being blocked by our innate inconsequence, even if there are no eyes and ears for it, and not waiting for salvation to come from above or across the river in New York – these are all matters of character, something that no longer exists in north Brooklyn today.

AFTERSHOT

Meanwhile, two blocks in from the waterfront, thirty years before their removal, natives eke out an existence in, what they would much later learn, was the squalor of a culturally deprived and economically depressed centuries old neighborhood. And with no amenities.Thus, in this final section, we take a look at the natives and their homes at the edges of the Monument. Often natives can be overlooked in the zeal of colonists, tourists and opportunists. let’s briefly look at the lives and homes of these folks.

Close by the waterfront native men wildly celebrate their own beautifully original culture, born on the streets of Brooklyn.

Near the waterfront, native women participate publicly in authentic rituals fraught with meaning, on the streets of their only birthplace and home. Msgr. Casato does the honors.

The Ugly Warehouse, North 6th Street – Unpretentious, dirty, old, direct, to the point and functional. No visual code required, nor Yale art degree. Still, one can’t help but notice a stark minimalist aesthetic along with the use of text well before such movements in art became a mainstay, and from a time and place considered to be populated by an artless sub-species without amenities.

One of the tenants of psychogeography is that the old days aren’t old at all, It’s just that things change faster now than anytime in history, and sometimes into something so completely oppositional, that it bewilders.

“Do we look blighted, depressed, unsafe? In need of your help? Your money? Your culture? You’re gonna preserve the character, differences and authenticity of my home – by replacing it?

You’re a pioneer? You land here and reinvent it in your own image, then declare, “We made your life better.”

It’s a joke…right?”

The Backyard View through my window on Union Ave. in 1989 – the factory and dwellings were fully operational and occupied, even during our own displacement. No longer are older sections of the city destroyed by economic collapse, but development. Often into something that it never was. What i mean to say is, the neighborhood was repurposed into an incubator of creativity, recreation and work, as well as being the birthplace of the nominally Brooklyn art life-style, complete with more quirky amenities than the best vacation spots.

High-rise luxury buildings and a 17 story tower have replaced the factory and the view of the sky (mysteriously there is a six story zoning limit). During the process of displace/replace we learned that we had been living in an abandoned, derelict, dangerous and dead place for all these years, and without cultural amenities (huh?) to boot. We were shocked to learn this, but comforted by our politicians, who, in cahoots with developers and banks, informed us that our regional history, culture, pride and rent laws would somehow remain in tact, and those suffering displacement would simply apply for an affordable apartment in one of the new tax-abated luxury towers. I know my history and that’s a much better deal than what the Dutch gave the Lenape in Upper Manhattan on May 4, 1626.

That’s why on June 29, 2005, the day our council passed The Willimaburg/Greenpoint Contextual Rezoning, we celebrate Christie Quin Day, where we always remember that aligning yourself with rich successful men, and seemingly being the next mayor, can backfire brutally because once every four years the voiceless are allowed to speak.

The Backyard View in 2002 – the factory begins to rent loft space to non-manufacturing hipsters, or professionals seeking the art life style, even while jobs and manufacturing continue on the property. Just as the factory is becoming a rental ruin while still operating, the realization that the property itself could be sold for a profit that was inconceivable since the booming industrial years, saves the day, if not the landscape.

The fetish of ruins photography always makes it appear as industrial cities were wacked into apocalypse in one swift transformation. That’s both a tourist move and a perception created out of viewing only an aftermath of all the tragic action missed. When these places die, they do so on their feet, resisting, usually for years, until that time that all morality, mortality, ethics, decency and sense, not to mention rent laws, runs out. In my case it took ten years off my life directly and five more, in recovery mode – all for a damn railroad flat.

Manufacturing and working-class real estate, make money, but not like finance and luxury real estate. The fetish of ruins only helps to advance this evolution, by representing sections of cities as mysteriously gone while obscuring the living resistance that ends in displacement, and can only end one way.

Home loss is as bad as they say it is. To lose everything you have built at the age of 60 is bad. But it’s also do or not profit time for the Master who must rid the premises of the tenant that has lived there responsibly and for thelongest time and pays the least rent, before the next lease is signed. Becoming a senior citizen, will close the door once and for all on the final shove out of a home i occupied for most of my life. Artists create, and remade my home and land so much, it vanished.

Ruins indeed.

Close by the waterfront native men wildly celebrate their own beautifully original culture, born on the streets of Brooklyn.

Hanging around Cono’s on a hot a summer night in 1989. Cono (not pictured) just sold his shop to Tony, the guy standing over JoJo in the window. Seated outside is the famous Tony V., strongman and champion ballroom dancer, he was featured twice in the old Ripley’s Believe It or Not books. Tony was born in the pizza shop when it was his parents’ home. The guy inside the shop with his perpetual cigar is JoJo Delio, the drummer in the famous Brooklyn Sym-Phony from Williamsburg, that played all the Dodger games. JoJo and Tony are both born on the block. JoJo finally passed in 2012 and was well into his nineties. Today it’s the revamped Driggs Pizza at Driggs and North Seventh, and in no time, no trace of these tight-knit multi-generational blocks exist, each, it’s own world. A place where you were born into and could spend nearly a century hanging around, is home in the truest sense. I was destined to end up the same, since i loved the place. But artists arrived.

Neighborhood legend, JoJo Delilio, backed by friends, family and neighbors during one of the Processions on his street, Driggs Avenue.

Dukie & <span class="audio-icon">🔊</span> TwoShoes at the Feast, 1998. Dukie died, 2005 of pancreatic cancer, i fought until 2013, then hobbled up to da Bronx. The Feast is still there – so is Dukey’s House of St. Cono, where he was born, grew up in and died, but mostly everything else, it’s all gone.

The Feast, going on for 125 years, has had to import “lifters” from Italian-American parishes outside of New York, to keep the celebration going.

The House of St. Cono, Paulie’s home, have their vigil every September which lasted for a week or two with a lot of god food and socializing, and another end to another great summer in Williamsburg.

The July Fourth fireworks along the waterfront Monument in 1986, as seen from the Conservancy viewing platform at my Home on Union Ave. Today the view is entirely obscured by new residential towers. Although the building where we viewed the fireworks is rehabbed, it is off-limits to anyone unwilling to pay a year’s salary to reside in a reinvented tenement whose worth is based on a zip code. No matter, the rooftop itself is no longer accessible by anyone, money or not, and is locked. As is the view.

Williamsburg National Monument is dedicated to the Brooklyn Sym-Phony and especially its drummer, JoJo Delio, also, the Brooklyn Strongman, Tony V., and from the Block – Jimmy Black, Paulie Capobianco, Frank Toumey and TwoShoes, everyday person and philosopher, also known as The Shooter. It’s rumored that TwoShoes was the inspiration for the Paladin character in the Have Gun Will Travel series, but who knows?

WNM is a certified Going Under project.