Infrastructure, meant to be forgotten although vital, important, is buried, then revealed.

The slurry wall refers to the “bathtub” infrastructure that formed the foundation and base for the Towers. It’s made to keep the Hudson River completely out of the site, and was of main concern during the attacks on 9/11. It held, and also part of it, literally, became a huge part of the Memorial Museum.

My target all along for memorializing the site was the tiebacks and the wall. I had a chance in 2003 to go into the pit and shoot it both at night and during the day, and, as it turned out, was just about at the stage of reconstruction that would, i think, capture the bare and raw infrastructure of the wall, before it was mostly covered, with a part of the wall exposed as an installation on the museum itself.

The area of exposed tiebacks have been cleaned up for display and are still impressive.

My mission since the seventies, has been to create a physical memory of something gone – the picture. I’ve shot a ridiculous amount of infrastructure, industry and transportation, and was buried in that, out in the Jersey Meadowlands when the planes hit, so it was a natural progression to the pit in order to shoot the wall and tiebacks at its most exposed and raw point before being buried or hid once more.

By this time i had been taking pictures of disappearing things in cities such as industry, churches, shops, homes, infrastructure, architecture, details and entire neighborhoods and even some cities, and, I knew the Wall, in its rawest form, prior to its rehab and eventual enclosure, would be of value.

Some could argue that photography itself, but its been disputed by the concept-world, is a memorializing machine. It’s one i have used to remember what’s gone. I’ve been in the memorial business since 1977, and have never stopped shooting what’s important, to the plebian, and about to disappear.

MEMORIALIZING INFRASTRUCTURE

A picture, as a moment in time, is limited compared to motion pictures, which can have tremendous duration. That’s why the singular picture is better at memorializing then a story, that, through its illusions, can give a detailed and complete picture, but not refine it to one thing, the picture.

I shot historic, but often little-known people, places and things on the verge of disappearance. Amongst the many industrial subjects i shoot, is the steel industry, but it could be anything including entire neighborhoods and cities themselves. Vanishing, much of it tied to industry, has kept me busy a long time. Now it’s development and gentrification fueling the disppearance.

The city, for myself, is a museum unto itself, interesting, open all the time, accessible and free. When i shoot something historic about to go, it will be a remembrance, so i put some time into it – literally, and, hopepfully it will better impact the viewer’s mind.

Don’t underestimate the extent of my work and a highly developed intuition that puts me on location at the moment of disappearance. I’ve done that for so long for so often I come up with the term, the Predictive Moment , which for me, is not the moment of disappearance, implosion or demolition, but the moment of return and before looking, absolutely know that he, she or it is gone.

Watching them disappear, like many did, and the billions that saw the videos and pictures of the disappearance, i said, well, everybody now feels like i’ve been feeling most of my life. It’s the same kind of hit.

By this time i had been taking pictures of disappearing things in cities – industry, churches, shops, homes, infrastructure, architecture, details and entire neighborhoods and evens some cities – for a long-ass time.

After shooting disappearing America since 1977 and living always in a disappearing urban situation, I developed a very strong sixth sense about disappearance. Disappearance also became the world in which I spent all of my time. By intuition I ended up in places that should’ve disappeared that lasted much longer and then fell apart.

It’s natural to memorialize, as it is to produce any culture. Perhaps art got its greatest boost from the need to create an object of memory, for any number of reasons and through any times, good or bad. But it’s the bad times and tragedy where we react most strongly to create something, first and foremost, not to be forgotten.

In such times any object directly tied to the event becomes charged with meaning by virtue of a connection only once removed, particularly these big historic events that can change our lives and direction.

Memorializing The World Trade Center, and memorializing in general, is among the most fundamental and oldest cultural processes. Even animals, like elephants, sometimes display unusual behavior with regards to loss. Objects, some ordinary, become charged with meaning after vanishings related to them occur. For instance particular or all photographs after a person dies, become charged with value and meaning and memory. Prized memorabilia of celebrities, sports figures and notable persons are valued like investments.

Utilizing existing objects as cultural artifacts charged with meaning, in the case of the World Trade Center, deep meaning, involving human tragedy large-scale and sudden, connected to war, politics and cultural identities. And also today, with our digitally-bred sensitivities, pandemics and large-scale terrorism, memory is magnified.

Obviously these are not typical museums, it will be a home to grief, bedrock grief.

What’s radical about the museum is the fact it’s set deep into Manhattan on three levels seventy feet down below street level.

A museum that went under, with displays of ruin, infrastructure, equipment, parts and vehicles, where the apparatuses now function as symbols of violence, loss and tragedy. Obviously, it’s a type of museum – built to house artifacts of a tragedy, It’s unique amongst memorials and museums that honor and remember this particular event, but no different than another memorial and museum displaying ruins. These museums are meant to display and speak about the unspeakable and are reserved for particularly heinous, stunning events like Hiroshima or Auschwitz.

To do not what’s unimaginable but, in fact, what can be imagined, can be done – annihilation through terror from other people who decided a group of folks, who were always “the enemy” had to go, and in the case of 9/11, the terror was orchestrated for both its immediate death and hurt, but equally as a symbol for their particular religious/political motivations. Both Auschwitz and the 9/11 memorial turn that symbolism inside out, and, in the case, of the 9/11 Memorial, uniquely, it was installed deep underground, where visitors must go under, no light is natural and there’s no choice but to go down. Even the fountains, as inverted waterfalls, do the same. After all, for years, it was The Pit. I wonder, will this hurt attendance, in these second gilded age happy times?

The slurry wall installation, a memorial created from raw infrastructure, that, of course, was meant to be hidden and buried, where it’s purpose and vital role would never be seen – keeping the Hudson River from flooding the site. It got the ultimate test and succeeded, i’m sure greatly satisfying the engineers and workers who built in 1970.

Japan, a country in WW II, that used suicide extensively in war, played into the decision to drop the Bomb, to break the will of an enemy whose level of self-sacrifice could never be matched. Suicidal bombers in airplanes deliberately crashing planes for the purpose of hurt, death and destruction, how do you prevent it?

Something so basic to humans, like creating memorial artifacts, is also continually done on a much smaller scale, for instance, in city neighborhoods and streets, honoring any number of events or people from both inside and outside the neighborhood.

After the planes hit the Towers, memorials sprang up in the areas of the Tri-State I had or always shot in – Williamsburg, Greenpoint where I lived, and industrial New Jersey which I was entrenched in for years. It’s, then, close to how I see things in general – locally and in the flow of life.

Speaking of that flow, when we live some place, landmarks both personal and iconic, become references and points of interest. We noticed changes, they look different during different times of the year and different lighting conditions. Seen on a daily basis, when something disappears, it has a particular impact related to experience and not representation of something as the big event.

RUINS

What the Hiroshima Peace Museum, Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and the the WTC Memorial Museum share is they are sites where innocent civilians would be annihilated. The toll of destruction for Auchwitz was 1.5 milllion deaths. All of these sites would have survivors, and as they die over the years, after these events, we are left with a wide record of the events.

Obviously, once utilitarian things become charged with meaning to the point of memorialization, that a venerations for things, that is in the upper reaches of historical respect, occurs.

Ruins photography explodes after 9/11. Unfortunately it was at that point that the Blue Collar Holocaust solidified after the abandonment from the Left years ago, to pursue, not class, but race and gender, and its (working-class) descent into the working poor and decayed neighborhoods, even becoming attached to cultural pleasures connected to apocalyptic imagery instead of social consciousness.

Ruins photography exploded, it seems like, just after 9/11. In retrospect. with all the turmoil, after years of economic growth, full employment, relative peace, the events of 9/11, obviously, changed a lot of things and ways of thinking. At this turning point of 9/11, the Blue-Collar Holocaust, that had been slowed so much by a stabile economy, began to pick up steam again and recessions loomed once more. At the same time digital cameras and the internet were beginning to take off, and soon there was a proliferation of ruins photography, mostly done by a generation who are the first non-blue-collar, educated service workers with a fascination for the artifacts of a time they just missed.

The Parthenon, the Colosseum, the Hiroshima Peace Museum are all ruins’ sites that were not particularly dolled-up and sugar-coated, let alone rehabbed. They’re left as is and as an exhibition of what was, and sometimes, what went wrong.

All night-for-day shots – the C-1 Blast Furnace, Cleveland OH – midnight, one hour film exposure, eight hours prior to demolition. Blast Furnace “D” Bethlehem Steel, Bethlehem PA – one hour film exposure at midnight – site “saved” as entertainment venue. Carrie Furnace, US Steel, Rankin PA – ninety minute exposure, 2:00 am, the site is supposed to be preserved as a memorial to steel-making. I wish the C-1 could be a memorial as well, but you get the picture.

Only pictures or actual paraphernalia of what’s vanished will memorialize. It’s disappeared, and this was its last shot, excluding its falling by explosive charges, eight hours later, in November, 2004. It actually began as Jones & Laughlin and was bought in bankruptcy by LTV Steel, which itself went under in 2004. Bethlehem Steel’s five furnaces and US Steel’s two Carrie Furnaces have been kept as memorials, the Bethlehem site is tied to leisure, gambling and entertainment, and is rehabbed and done, while the Carrie site is to be made into an actual direct remembrance of the massive steel mill called the Homestead Works that the Carrie Furnaces supplied with molten iron. It still needs funding for its memorial project.

Bethlehem and Carrie were shot utilizing a full moon as the lighting, while the LTV Furnace was also a long hour exposure, but utilizing the lights of the city as bounced off a high, dry, cloudy sky, emphasizing the idea of time – both passing and standing still.

Basic oxygen furnace, Wisconsin Steel, 1981, and the ore yard and docks of Acme Steel (Interlake) during its demolition in 2004, one hour exposure at 3:00 am. No preservation at any of the steel mills that lined the Calumet River in south Chicago. There remains a memorial to the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937 that took place at the now gone Republic Steel mill where ten people were killed.

Along the Calumet River, Wisconsin Steel shut abruptly in 1981, throwing 4000 workers out of their jobs, and was the first of many large shocks that would hit Chicago, the industrial city, and eventually change it into what it is today, by virtue of heading in another direction. The Chicago District of the American steel industry was entirely wiped out, and there are few traces. It began with Wisconsin steel, but two mills hung on, until 2001 – Acme (Interlake) and LTV (Republic) when they closed permanently and there was no longer any of the big mills left along the Calumet River.

42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, 1988. And downtown Manhattan from the Landfill 1-E on the Kearney-Arlington border in the Meadowlands, August, 2001. Both sections of Manhattan have been thoroughly transformed. The new tower that took the place of the twin towers is meant to memorialize freedom. The rehabilitation of 42nd Street didn’t incoprorate memories of the good old bad days.

SENSE OF PLACE

We have certain relationships to our home turfs, and the landmarks there. That landscape of home is filled with overly-familiar scenes and things, we see every day and hold some meaning. For residents of north Brooklyn, for instance, when returning home, the sight of the Greenpoint Holders or “The Tanks” meant you have arrived back home, and for most of us the Towers represented the same thing coming in from the west, Jersey and beyond.

The twin towers were not warmly received by critics. Lewis Mumford compared them to a gigantic pair of filing cabinets, but they still would transcend fashion, art and architecture and become embedded in the shared psyche of the city, especially if you saw them every day, right out your front window.

From my front window when i lived on the third floor, Union Avenue, Brooklyn, 1986. When built, Lewis Mumford compared them to a gigantic pair of filing cabinets but everyone ended up liking them, and were a pleasure to see. I did freelance photography work at corporate events at Windows, and those were always some of the best jobs. Shooting folks socializing all night and every once in awhile getting to look down on my neighborhood in Brooklyn. I remember the WTC, the view out my window and my neighborhood as some of the best times of my life if not the best run of time i’ve ever had.

It was a real kick, when i worked there, to look down on my neighborhood and block from Manhattan, return home and have the view back at the Towers.

Gantry crane and WTC from the Navy Yard in Brooklyn, 1986. As a waterfront neighborhood, Williamsburg had a constant view of some of the city’s most loved architecture and infrastructure. I took this picture on a quiet early weekend morning, as i crossed Division Avenue to access the pier to take this shot, i was aware of a lone car moving towards me. With each step that car, a fast one, gained steam, just as i began to hurry the driver crossed the center line and came directly for me. I did a hop, i could feel the driver’s side mirror, brushed my back, and as i turned to look at the driver, the car drove directly into a fire plug, and he smashed against the wheel and windshield. When i got to him, the door wouldn’t open, he was bloodied, somewhat conscious with his nose hanging off his face.

From my roof just after sunset on 9/11. In 1995 i moved to the second floor, on Union Avenue, Brooklyn, and no longer could see the WTC as well, on the night of 9/11. I went to the roof. A strong northwest wind brought the smoke into the Brooklyn Heights section. Johnny, across the street, on his roof, and i, said some things, “On Guliani’s watch, right?” And we watched the skyline for a long time. That “smoke” stung.

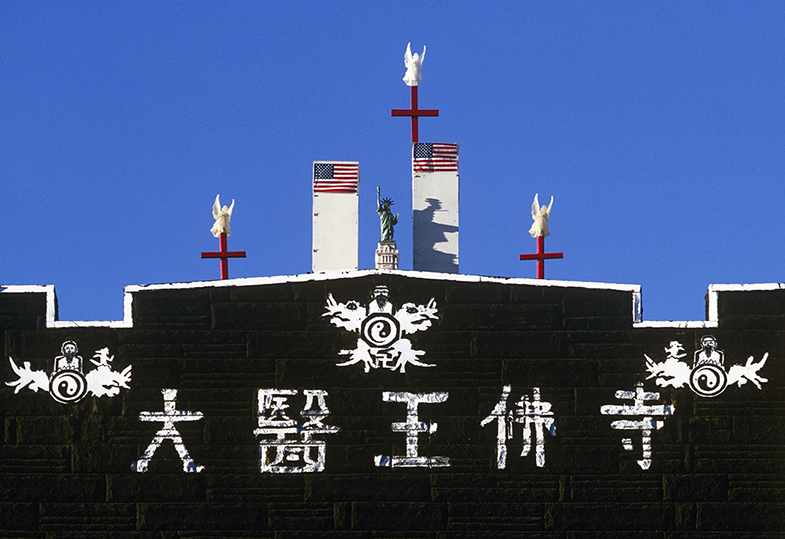

Immediately memorials sprung up all over the city, and particularly in places where the Towers were part of everyday life. An Asian karate studio on Norman Avenue in Greenpoint made this memorial to the WTC.

I went back to shooting Jersey where i had been entrenched for six years in the industry and infrastructure out there. By this time i had developed some good instincts with this landscape, and ran across this scene at Hugo Neu Schnitzer East, of Jersey City, N.J., where 250,000 tons of WTC scrap steel was sliced into pieces by industrial guillotines and torches, for shipment to eleven countries including Japan, China, Malaysia and South Korea. It was unusual on a scrap level because it was the heaviest steel ever used in a building, with some sections being two feet thick.

VIEW a more detailed summary of the sale of scrap from the WTC.

Jersey provided great views of the annual Tribute in Light event, another memorial to 9/11 involving the tristate and so many who were connected to the site.

The source of the Tribute in Light in downtown Manhattan.

Kaaterskill Falls, 2019. Continueing with a long strenuous project that i had connected to 9/11, and started in October, 2001, involving the action of local waterfalls.

The inverted fountains that were constructed at the base of each tower echo the event itself – a sudden unexpected vertical drop, and a larger metaphorical fall, many knee-jerked into let’s get ‘um, but i still feel only loss. They got us good. We were asleep.

THE WALL

Popularly called the bathtub or bathtub wall, the barrier was actually only meant to keep the Hudson River out of the site. After the attacks a major concern was damage to the wall, which sustained damaged but completely stood up.

The slurry wall is 4 feet thick and roughly 100 feet deep. Although a stretch along Liberty Street shifted more than 10 inches on 9/11, it managed to keep the Hudson River from breaking through and drowning the smoldering Ground Zero site with water.

The Bathtub contains a 16-acre (65,000 m2) site, including seven basement levels, the downtown terminal of the PATH rapid transit line, and the preexisting New York City Subway’s IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (1 train). The South Tower of the World Trade Center was actually built around the PATH tubes that passed through. Its deepest basement level is seven stories, and it totals 3600 feet in length.

Slurry is a solution of bentonite known for its absorption qualities, it’s a clay.

The Wall fit into my usual mode – it was local, and, if it wasn’t a big deal at the time, it would become something over time. Connection to the historic has always been a a kind of dividend to photographic capture.

Slurry wall, instinctively is what drew me to the site, like nothing else.

Something vital, important, buried, then revealed.

The wall in relative daylight, 2003. The seventy foot wall and tiebacks, from above street level to bedrock is visible, an area of which, is now part of the 9/11 Museum, that will be buried itself, down to bedrock.

I had been shooting the infrastructure of the Meadowlands and industrial Jersey all the time since 1995, going deep into the landscape there, particularly all the tunnels leading into Jersey and New York from the west. Going into the pit, shooting the infrastructure there was just an extension of what i had been doing for eight years, and thought it would have value in the future. I even got to walk to Jersey City through the closed Path tubes and back, while waiting for night.

Obviously there is already good information on the Wall, and rather than add another layer of copying to the subject at hand, you can go to another source of information, while i bring what i know as being there before it was covered and the infrastructure was laid very bare.

Memorializing infrastructure for so long, the tiebacks and the wall seemed the ideal site for shooting. I had a chance in 2003 to go into the pit and shoot it.

The Wall, in its rawest form, prior to its rehab and eventual enclosure, would be of value, at least that’s what i thought.

I also had been generally underground in a long going under phase in my life and shooting, so, in many ways, when it came to being in the pit, shooting infrastructure in its rawest and most hidden form, was right up my alley.

The day in 2003 i got a chance to shoot the wall, i saved it for twilight and night, i guess, because i had been living and shooting by night intensely since the late eighties and that’s just when i shot. That day, for the hell of it, i walked through the PATH tubes to Jersey City then back to the pit to shoot the tiebacks and the wall. I wouldn’t buy a digital camera until 2013, and this was still the Golden Age of Color Film, and everything here originates on film. The site had been cleared out, the foundation and wall was nearing completion, and, in March, 2003 i thought the site was ready, at peak rawness, that soon would disappear again, except for the sections on display at the 9/11 Museum, so i got busy and shot it.

The city as a museum to itself, and a memorial created from raw infrastructure, that, of course, is right up my alley.

The slurry wall was meant to be hidden and buried where it’s purpose and vital role would never be seen – keeping the Hudson River from flooding the site.

The slurry wall is 4 feet thick and roughly 100 feet deep. Although a stretch along Liberty Street shifted more than 10 inches on 9/11, it managed to keep the Hudson River from breaking through and drowning the smoldering Ground Zero site with water.

The Bathtub contains a 16-acre site, including seven basement levels, the downtown terminal of the PATH rapid transit line, and the preexisting New York City Subway’s IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (1 train). The South Tower of the World Trade Center was actually built around the PATH tubes that passed through.

Slurry’s most important ingredient, bentonite, is a clay that expands and absorbs like no other.

The museum took fifty shots of mine for their archive after doing freelance work in the Pit, off and on, i always thought, the writing was on the slurry wall. A piece of infrastructure can be charged with so much meaning.

The Slurry Wall is a certified Going Under project.