Chicago was The Blue-Collar Metropolis. It was Buffalo on steroids, set in its extreme flatness where the prarie edges the Lakes. When you had many cities, many of America’s largest, that had populations that the were majority blue-collar. Easy to understand when you realiz the, in a place like Chicago, plants and industry were strewn all over the city, and a single facility could easily have tens of thousands of workers. On the far south side, in 1979, four fully integrated steel mills probably had 22,00 workers, down from the peak, for all industries, that occurred from 1941 until 1979. The same mills in 1950 has three times as many workers.

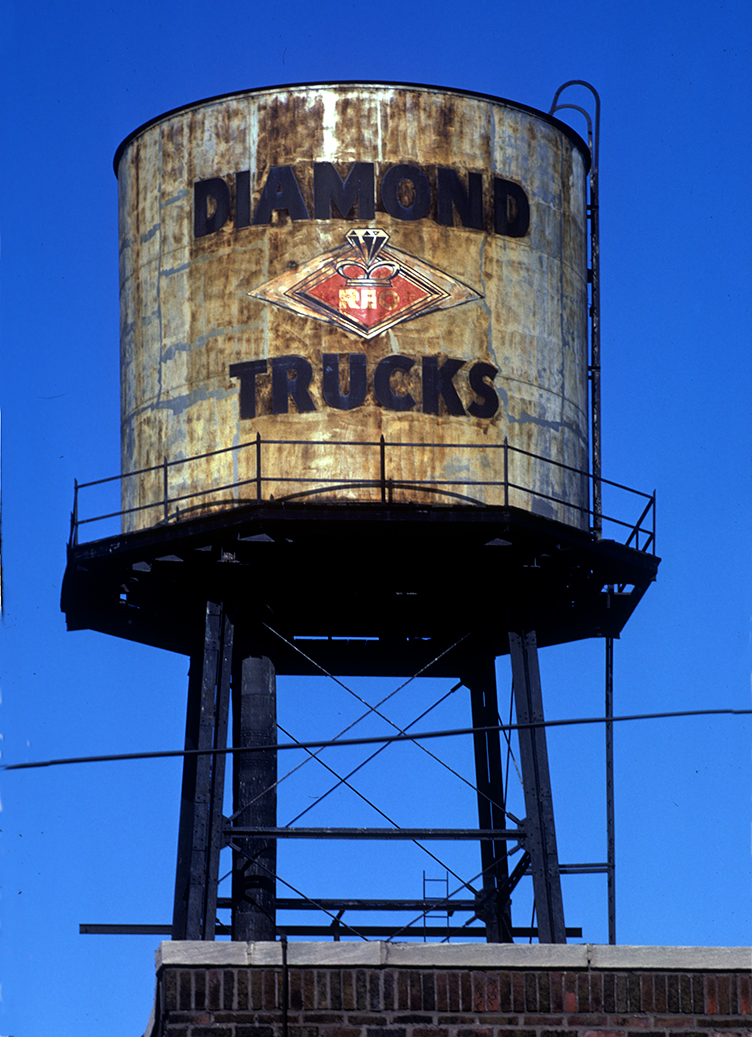

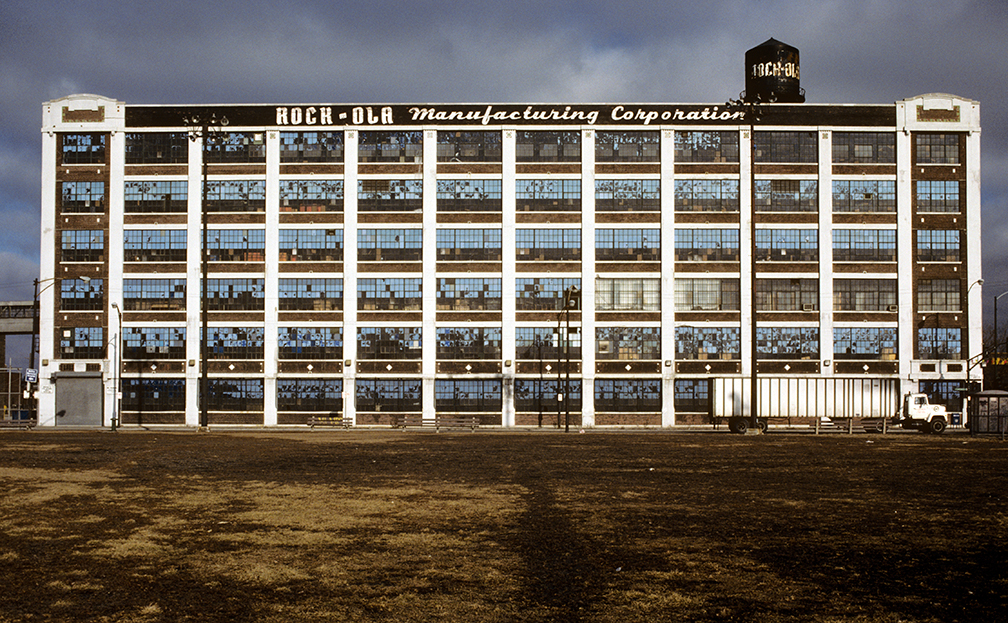

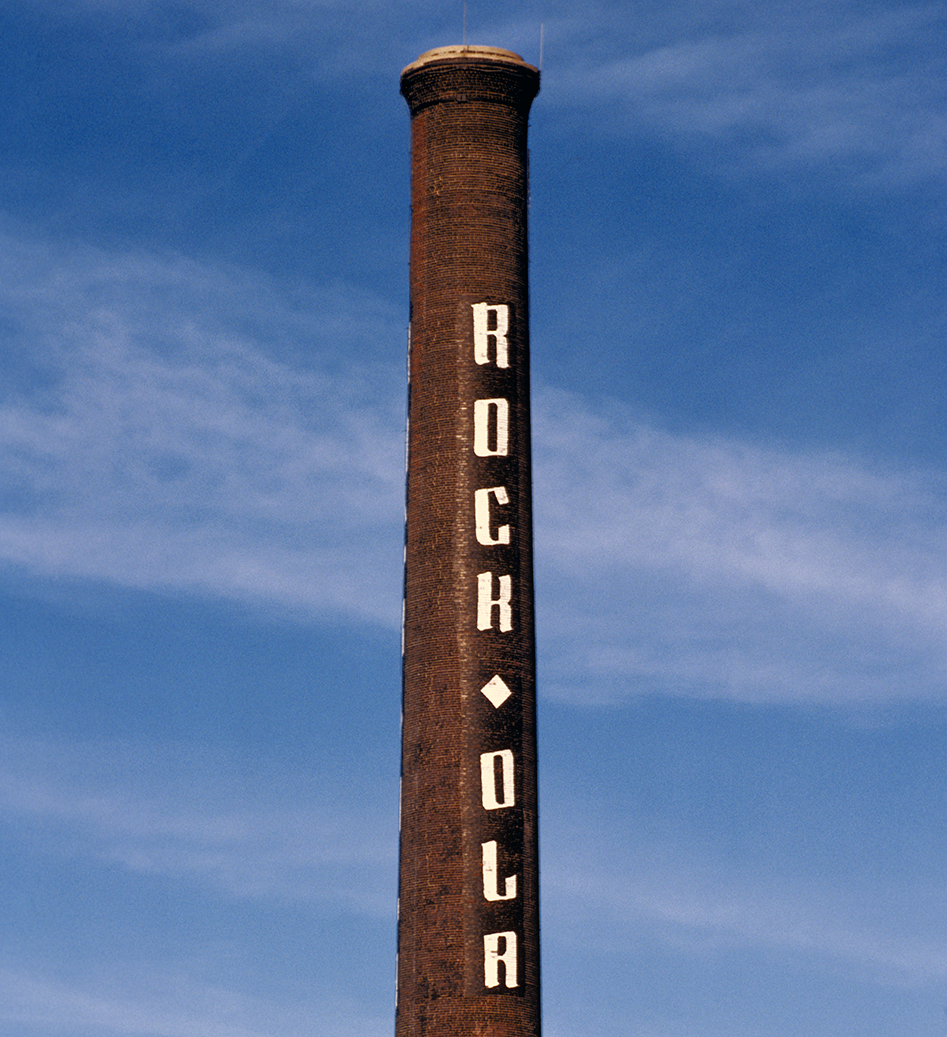

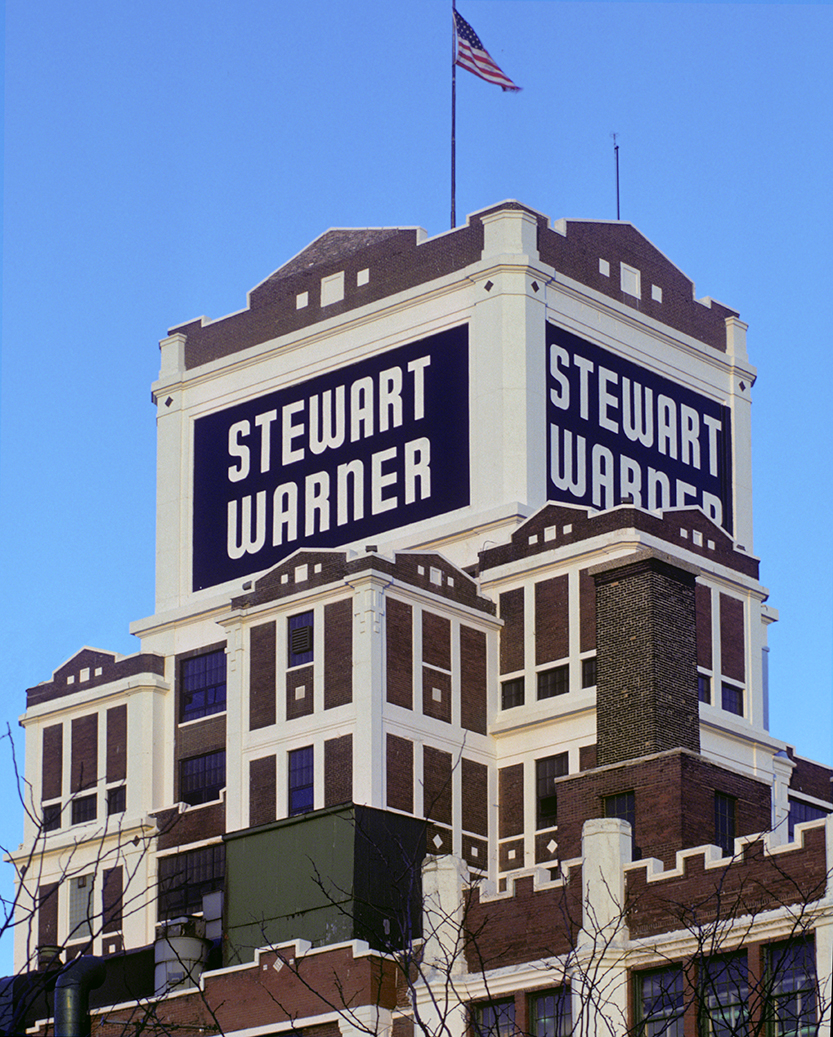

Western Electric on the far west side, out by Cicero, had, at its peak, 40,000 workesrs at one plant. This is similar to China’s industrial growth today with masses of workers staffing facilities that are actually much larger tham the American boom years. Stewart Warner, on Diverey, in Lakeview on nthe near northwest side, employed 6000 in their castle-like plant built in 1905. Its clock tower was monumnetal in an era when time and money became more important than ever, and, Chicago the manufacturing giant, had plenty of clock makers around.

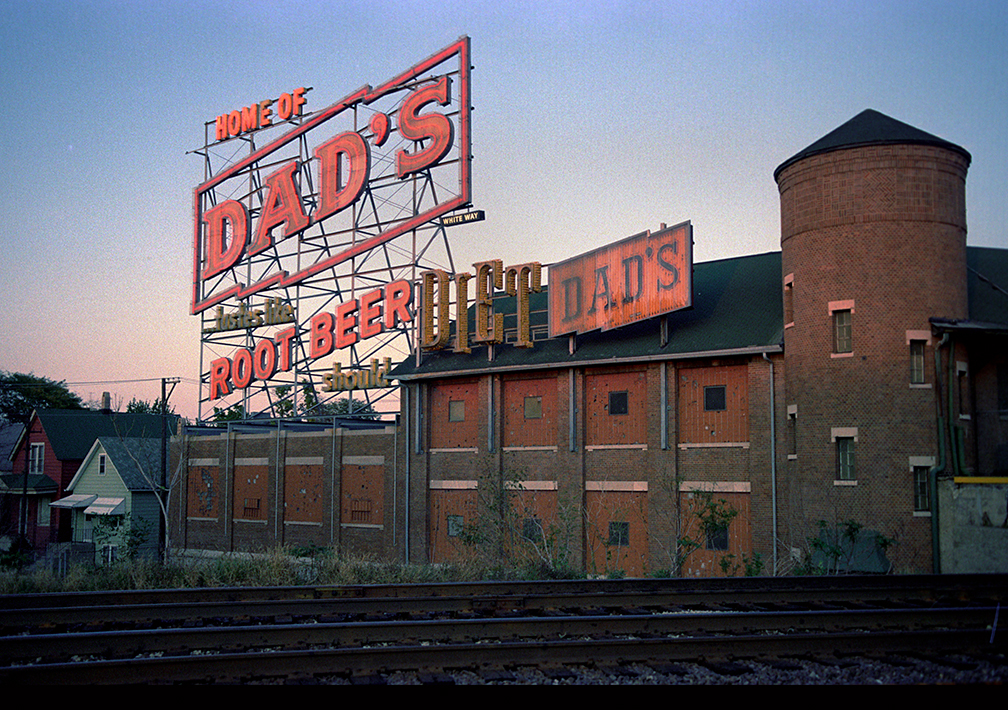

Another classic castle-like plant was two miles west, where Dad’s made its root beer. Like allChicago industry it was nestled in a resedential neighborhood. A strett tht deade-ended outside the plabt would bathe the houses in a red neon glow from a sign that seemd the size of the plant itself. Neighbors would hear typical Chicago sounds that wee around for 150 years – machinery, trains, tricks, bottles clanking and crashing.

Bicycles? Another large plant smack dab in the middle of resedential blocks, Schwinn, was one of thirty bike makers in the city, which, of course, was the nation’s supplier of bicycles since it became a huge American fad. Schwinn hung in there as the last, and until the end in 1992. This plant is a fundamental example of the impossible challenges American maufacturers’ would deal with, until they ended.

Trying to earn a living and paying bills consumed of a lot of my time while in Chicago, and, most importantly, most of my photographic time was taken up by the steel Mill’s on the southside. Whatever I could I would get out into the neighborhoods and document the industries and plants which I knew we’re not going to last much longer. My time was up in Chicago in 1986 and I moved back to New York.

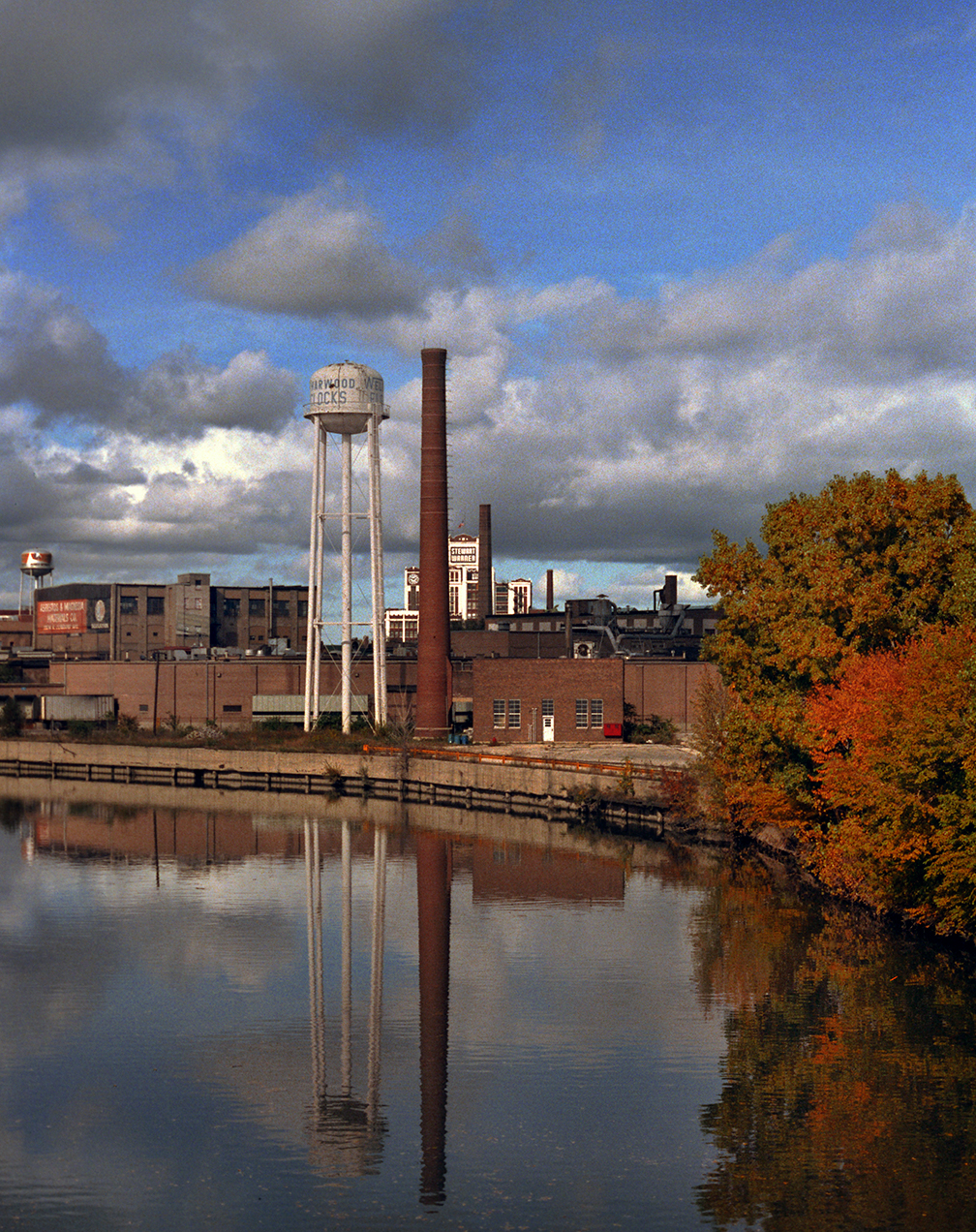

The Chicago River at Fullerton Bridge

The river was lined with industry on the North and north and west sides, and corridors, like Clybourne Avenue, that paralleled the river, were also lined with industry. All these places are gone and have been gentrified.

That line of water tanks and chimneys were attached to plants that employed many thousands of people. In the background you can see Stewart Warner’s castle-like plant that employed so many at good paying union jobs it wasn’t funny.

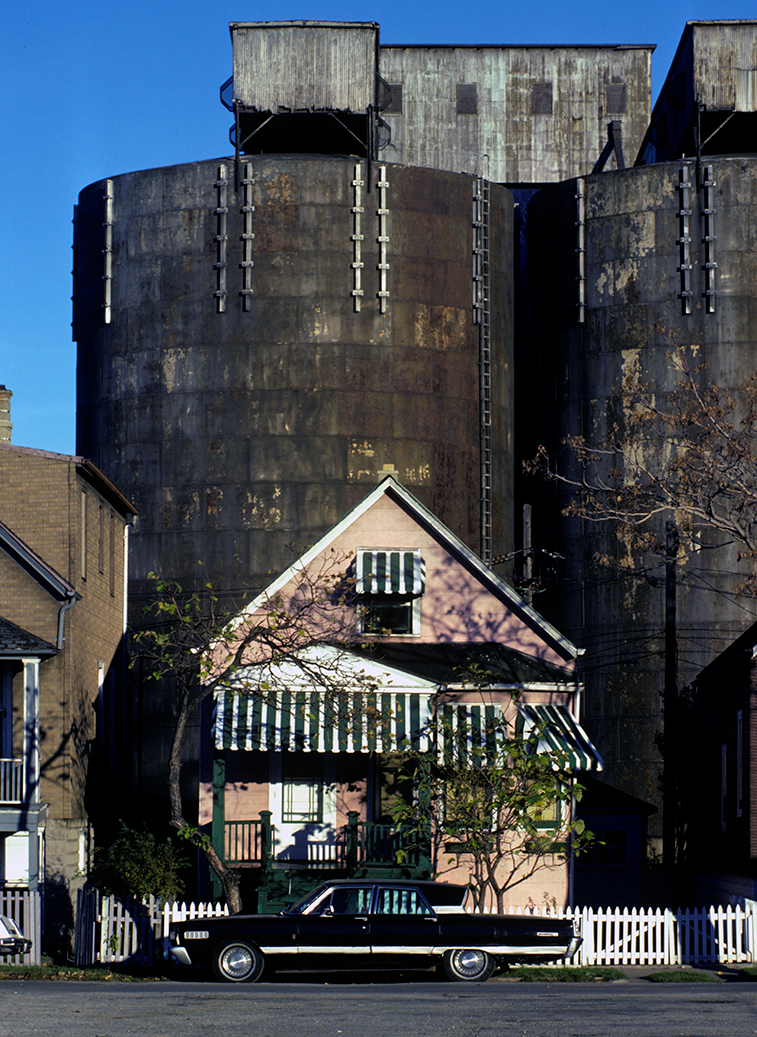

Finkl & Sons Foundry

Located on the north west side, Fikl & Sons did eventually relocate, due to the gentrification, but back in the day, this was a typical scene if wandering the streets of Chicago, even at night, when this picture was taken. You could stroll the neighborhoods at 3 AM and pass factories that were entirely lit up and staffed with people busy making products. And the sound of that was everywhere.

Dad’s Root Beer Plant

The plant was locatted on Washtenaw Avenue, and is mostly gone except for parts like the turret that was incorporated into a new condominium complex.