INTERLAKE STEEL, 1980:

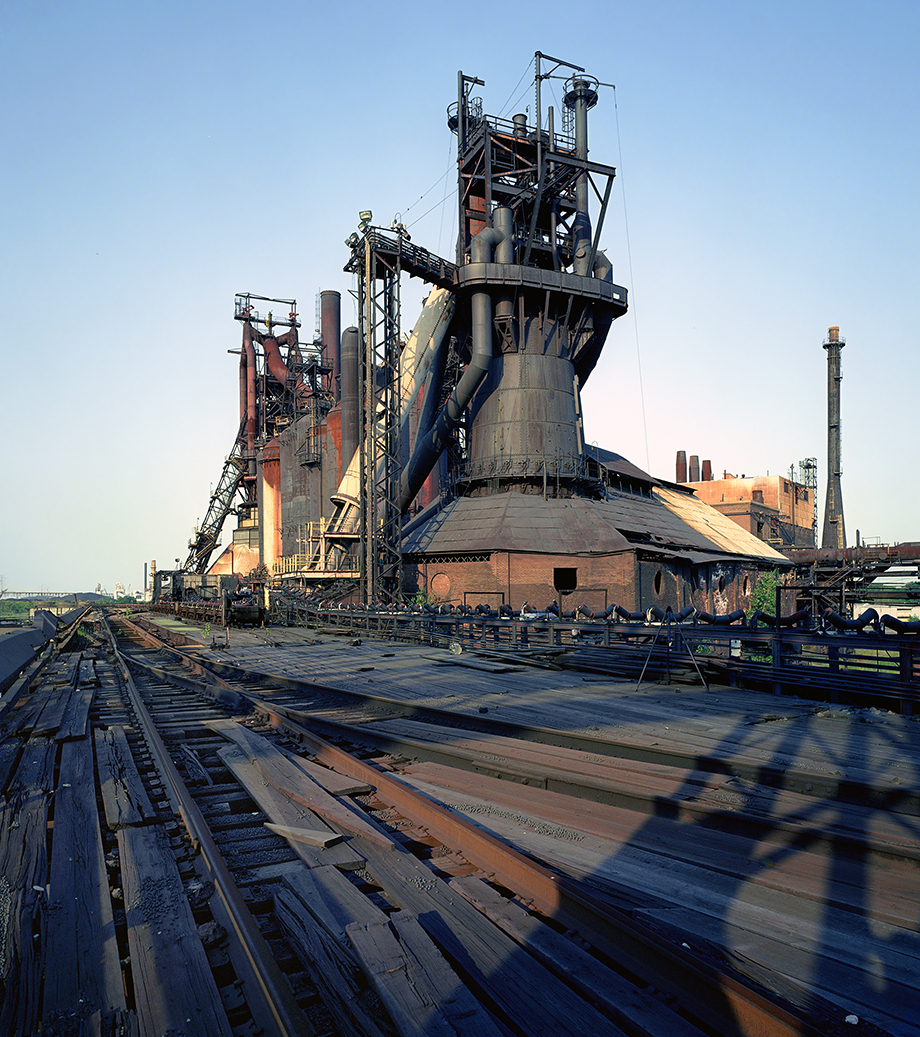

Interlake Steel (Acme) 1980 – Blast furnaces “A” & “B” ore bridge and piles of iron ore along the Calumet River. Interlake Steel merged with Acme Steel in 1964. These two furnaces produced molten iron, that was carried by bottle rail car to a basic oxygen furnace for conversion to steel, 13 miles away in Riverside Indiana.

23 years later:

Acme Steel (Interlake), 2003 – Blast furnaces “A” & “B” – an empty barge and ore yard along the Calumet River.

THE LOST STEEL MILLS OF CHICAGO’S SOUTH SIDE

Disclaimer:

For many years now, a ruins fetish has undermined actual documentary work in the Rust Belt. Generations, who never saw a steel mill or one in operation, ignored the roots of one of the most historically grounded indusrtries in America, in favor of rust belt “coolness” or art whose connection to its subject begins as art – the look of ruins, and their history in art, without any experience in them or their intrinsic histories, has dominated domestic documentary photography for years going back to 9/11, at the moment of the birth of widespread internet usage, where so much of this imagery exists.

And was it that event, that finally woke us out of our prosperous but preposterous self-involved techie dream state? The disaster itself was thoroughly documented, with downtown Manhattan home to many professional photographers and media people, and NYC, itself, a center of media. Some set up their 8×10 view cameras to capture the event in the blinding clarity of the descriptive truth of physical reality in real time. Soon after 9/11 ruins photography took off, and is finally beginning to cool, after establishing itself as a weird fetish genre, practiced by everyone, including museum board directors, renting helicopters to depict Detroit’s devastation and, also, becoming quite the internet/art party event, culminating in Andrew Moore’s Detroit Disassembled at the Akron Museum of Art, a huge success, perhaps pushing more, in the same direction – images connected to art or pop culture, but not the subject itself, that, if depicted in a continuum over 42 years, combined with actual experience over a life time of what’s depicted, then one might really have something to say beyond symbol or reification.)

RealStill began its depiction of steel in 1977, as the Rust Belt started, never as sad disappearance, but basic awe, and, as they fell, i would be there too – to the bitter end. Back then, very few did this sort of thing – two, the Bechers, had a beautiful, historically accurate depiction of steel before its fall. Curiously Hilda Becher insisted that their endeavor was not art, but photography. Doesn’t the number of photography galleries reflects this, too? RealStill is not connected to art, its canon or its present state.

RealStill, always embedded, could never dream of categories, such as whether something was supposed to be art, journalism, or “porn.” Being embedded, means categorial erection ain’t my job or anything i ever would think about, which is only to do my best to conjure a picture of vanishing industry, that i have been connected to since birth. In short, i do my job.

The Lost Mills of Chicago in Action, the Birth of Their Decline:

The Lost Steel Mills of Chicago was captured in two segments – the first segment was shot between 1980 and 1983. During this time the mills were in full operation, but just at the very beginning of their demise especially with the closure of Wisconsin Steel in 1980. The second segment was shot 22 years later in September and December, 2003, when, after being shut for two years, they began to be torn down. All steel production on the Southeast Side ceased in 2001 and all the plants were pretty much gone by 2004 in a scenario that began in the late seventies.

St. Michael’s, Russell Square, South Side, Chicago and a center piece of the South Side, where only church steeples competed with the chimneys of the mills. Mill, church, bar and home, an industrial neighborhood.

On the Southeast Side of Chicago, in the spaces where the steel mills didn’t lie, are the four residential neighborhoods of Chicago’s steel district; South Chicago, South Deering, East Side and Hedgewich. Some areas were dwarfed by the industrial lands all around them, as in South Deering, an area whose 6-square miles had only a half a square mile of housing, the rest a home for heavy industry.

Chicago, for a long time, had a significant history in metals production. The city’s heaviest industries like integrated steel mills, were in the four neighborhoods around the Calumet River that grew around the steel that has been made there since the Civil War. The south end of Lake Michigan would become the major steelmaking center of the country, part of a carpet of mills, factories and refineries that spread out beyond South Chicago – south and east along Lake Michigan – Whiting, East Chicago, and Gary, whose very name is industrial in its origin.

Built during an era of labor strife as well as industrial paternalism, home and mill, factory and residence became cemented. Later the company towns and paternalism of men like Pullman and Hedgewich would fade. There would be more more labor strife culminating in the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937, which occurred near the entrance of the old Republic Steel Works that was on Burley Ave.

Back when the iron industry began to find fertile ground here, it was called, Irondale. That unity of the pastoral and industry was true and nature hung tenaciously around the mills, particularly in South Deering until slag and waste found so much a home in South Deering that one enclave was even known as Slag Valley. In South Deering, once you passed Wisconsin Steel on Torrence Ave., there wasn’t much, certainly the most wide open land in town, but also a no-man’s land and wasteland fitted only for industry. But certainly by the time you reached Hedgewich, a little to the east, nature and water abounded on the flat prairie, as well as, a big sky. And Hedgewich, still today, the best of the four neighborhoods that were squeezed in amongst the mills of the Chicago Steel District.

Wisconsin Steel, 1985 – The building on the left is the basic oxygen plant, to its right is the coke plant, beyond that, blast furnaces, The shot was taken from a staircase on the Interlake/Acme coal/coke conveyor that ran over Torrance Ave. left of camera and out of frame.

Living amongst these mills, all of which made steel in the dirtiest way, from scratch, meant living with the sounds and smells of coke plants, blast, electric and oxygen furnaces, and all the other mill equipment. Sirens, foghorns, motors, engines, clanging metal, falling metal, explosions. The night sky could glow red from the pouring and transfer of molten iron and steel, as well as, the flames and carbon smoke of the coke ovens. I would call it a sublime feast for the senses.

And many would leave their homes only to work at one of the mills nearby.

As far as the “river” is concerned it’s largely man-made, dredged, and bulkheaded for 150 years.

CHICAGO STEEL (1980-1983)

The first segment (1980-1983) features US Steel’s South Works at the mouth of Calumet at Lake Michigan, Interlake Steel and Republic Steel further upriver on the Calumet River’s east side, and, across the river on the west bank, Wisconsin Steel and the Interlake Coke Plant. At this time US Steel had begun its long shutdown and Wisconsin Steel was just about to abruptly shut down on March 26, 1980. All of these were big integrated mills that could produce vast quantities of steel by consuming and processing mountains of iron ore, coal and limestone, with blast furnaces, coke plants, finishing mills, ore and coal docks.

The Interlake Coke Plant (later, Acme) and Wisconsin Steel, in South Deering, was located on the west bank across the river from Interlake Steel (later Acme) and Republic Steel (later LTV) on the East Side of the Calumet River. South Works was at the mouth of the river and along Lake Michigan and fostered the Bush neighborhood. Another big mill, longer gone, sat across the Calumet from South Works, Youngstown Sheet & Tube’s Chicago Works which was originally the Carnegie Steel Company. Hedgewich is the last neighborhood before Indiana on the South Side and runs along the east bank of the Calumet. Here the steel mills ended, the land opened, but factories like Ford’s assembly plant, which is still operational, are still here.

The south side, largest in area of all Chicago neighborhoods prides itself on and disdains the rest of the city for, its isolation. Generally the further south and east you went in the south side, the better the neighborhood, with Hedgewich, originally another Pullman style company town, being, still to this day, a great neighborhood.

Many mills like Bethlehem in Pennsylvania were mill towns with very coz residential areas surrounding the mill, but not US Steel who, probably wisely, set their mills as separate of the surrounding neighbors, by the use of the terrain and waterways, or railroad tracks, or, in the case, of the Bush, a wall.

Further south is South Deering, not much better, the classic mill slum, and jumping off point for first generation workers. Today its devoid of steel workers but stable like the Bush.

South Deering is Chicago’s largest neighborhood at 11 square miles. It’s residential area is one half square mile and minuscule compared to the industry that once dominated the landscape. Today it has a population of just 15,000 in a city of 3 million, ten times less density than the average neighborhood, and with all the big employers, the steel mills, gone, there’s even less reason to live here, beyond isolation.

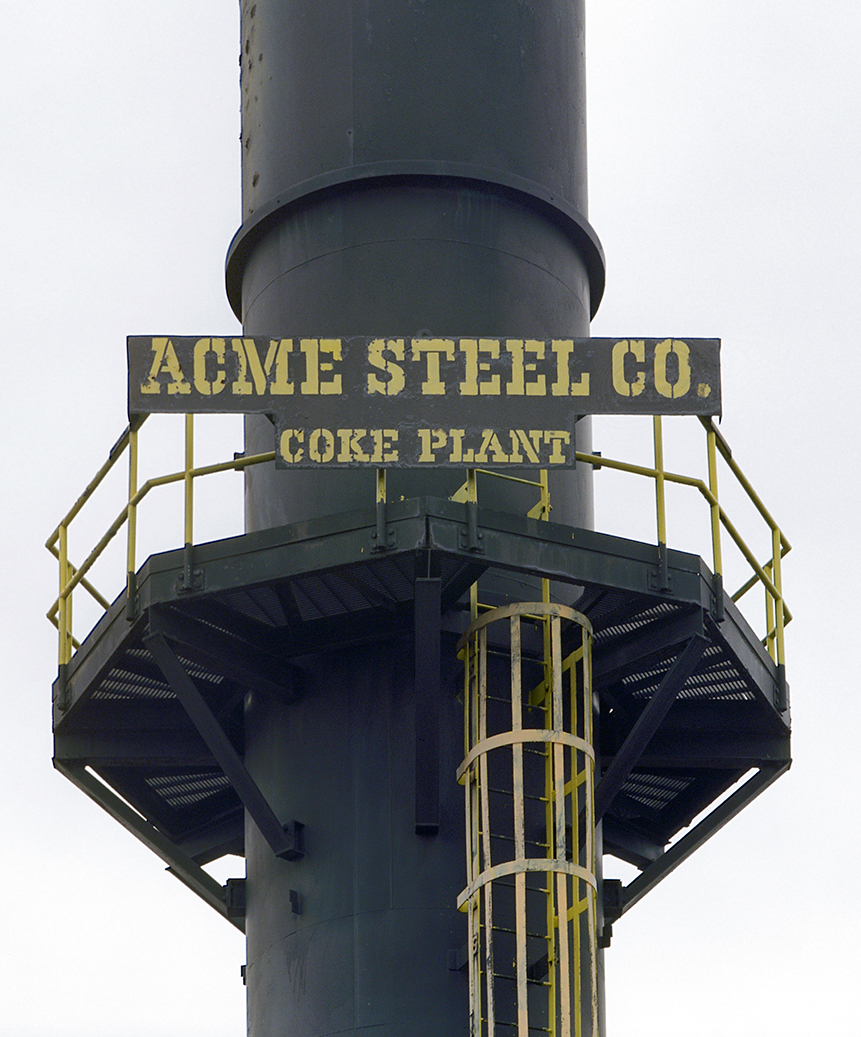

Nearby Acme’s coke plant, along Torrence Ave. was hardly residential. Basically there were no residences for miles down Torrence Ave. with one exception – on the south end, below the plant, were a handful of homes, while at the north end were the first residential blocks of South Deering, which faced the expanse of the coke plant, with two giant gas holders off a bit to the west. If that wasn’t enough, directly across Torrence Ave, to the east was the beginnings of the very large Wisconsin Steel Works that ran for two miles along Torrence Ave., across from the homes of South Deering.

Interlake Steel, Coke Plant, Quenching Plume, Torrence Ave. – just south of the Interlake (later, Acme) coke plant on Torrence Ave. – every couple of minutes a plume of steam shoots out of the quencher tower, where water is poured over red-hot coke out of the ovens. Every time this happen a siren goes off. Here South Deering and Slag Valley is truly a no-man’s land, and still is today, yet on the north edge of the plant there are many homes and the beginning of the the old gritty Torrance Ave. commercial strip. Now silent but folks who were here for a while still talk about that siren, and the general indusrtrial noise of a coke plant, It was also absolutely the biggest producer of toxins for any mill. These folks would breathe the hydrogen sulfide, benzene and a myriad of other pollutants, along with that siren.

East Side, probably the least recognized Chicago neighborhood, even by Chicagoans does stick further east into Lake Michigan than any other area of the city and it’s far from State Street and the Loop. It’s comprised of the east side of the Calumet River from its mouth down to 126th Street and lake Michigan to the east. It’s has a fair size, though not huge like the North, South and West Sides. But with Lake Michigan on one side and the old Calumet mills of Republic and Interlake on the other, it was a separate land.

Steel making took up most of the banks of the river and all navigable water was utilized for industry along every inch of the river from the lake Michigan into Lake Calumet. The borders of residential sections of Hegdewisch and East Side, South Deering and the Bush, were defined by the mills that were themselves, in some ways, defined by a river that could only be seen from one of the moveable bridges that crossed it.

US STEEL

Mural – in 1980 when the hot end pretty much shutdown, the locals created this mural on the side of a bar in the Bush.

The Bush neighborhood ended not at Lake Michigan but at the walls of the South Works. It’s a sub-neighborhood of the South Side whose centerpiece is St. Michael’s church and Russell Square Park. The other park in the neighborhood, Bessemer, is named after the iron to steel process. Bush was pretty tough back in the mill days. The streets closest to the mill were old and built before Chicago raised its streets and sidewalks. Thirty-five years ago there were plenty of abandoned homes and unkept lots. It was, literally the Bush. It was the original mill hood, where each succeeding ethnic group landed while working in the mill. After a while, if one could move further south or on the east side of the Calumet River, there were newer homes in neighborhoods like Hedgewich and East Side.

Today all the empty lots and snaggletoothed streets are neatly done, but 35 years ago this smelly area by the mill was a classic mill slum. Further out, of course, things got better and the Bush today is still moving on, and like a lot of cities, it doesn’t look nearly as old and run-down as it always was most of its time during the dirty years.

US Steel South Works, Employee Entrance, Bush Neighborhood The South Works closed gradually beginning in the seventies. By 1980 there were still 10,000 workers but, by 1992, when the last 700 workers were let go, the plant would permanently close. Today no trace remains of the old giant mill.

South Works began in 1857 as the Northern Rolling Mill, later Federal and finally U S Steel in 1902. U S Steel would become the largest Chicago steel mill. In 1952 15,000 workers operated eleven blast furnaces, three open hearth shops, eight electric furnaces, twelve rolling mills and a foundry. That’s a big mill, a very big-ass mill.

US Steel, South Works, Employee Entrance, the Bush The finishing mills loom over the wall.

Some mills, like South Works which closed for good in April, 1992, had a very slow decline that began in the seventies, as various departments that were no longer profitable and were simpley shutdown.

US Steel Main Gate, The Bush, South Chicago This gate led out into the Bush neighborhood of the South Side. Blast furnaces and ore bridges can be seen in the background. There was a real “political” history to American steel in these times, and security was tight, particularly around the hot ends of the mill, which were surrounded by the least desirable neighborhoods – stepping-stone neighborhoods – where some stayed, but most moved because it was funky with mill smells.

All this seemed to go on in private as US Steel liked its mills sealed to the public and South Works was no exception. Blast furnaces and ore bridges could be glimpsed only on a boat on the water. The development of neighborhoods like the Bush, which ran up to the walls of the mill on its west side and the industry along the Calumet to the south, came into being because of the mills.

Moving south along the Calumet River were the Wisconsin Steel Works that supplied steel for International Harvester. International Harvester had owned Wisconsin Steel for 75 years, using it as a captive supplier of steel for its farm equipment. But Harvester did not invest in Wisconsin Steel, sustained years of losses and finally sold it in 1977 to Envirodyne, a California company with no steel-making experience. In March 1980 the entire mill closed without notice, and, along withe the closing of Youngstown Sheet & Tube, became early symbols of industrial divestiture. The shots below are from 1982-1984.

WISCONSIN STEEL

Main offices for Wisconsin Steel.

Entrance to plant office. The International Harvester logo was taken down when Endodyne bought it, then closed it.

Finishing Mill.

Rolling mill on East 103rd Street the northern boundary of the mill.

The basic oxygen plant along Torrance Ave., in the right background are the ruins of the coke plant.

Basic oxygen plant, the International Harvetstor logo was still here, after Enodyne bought the plant in 1980.

The blast furnaces are in full demo, the toxins in the giant stoves allowed them to linger longer, until a final expensive remediation.

Hot end sunset, November, 1981, from the east side of the Calumet River.

REPUBLIC STEEL

The Republic Steel site began producing steel in 1916. Peak employment of 6,335 was in 1970, and, in 1977 Republic added two Q-BOP shops (which make low-alloy steel). In 1984 Republic becomes LTV which significantly upgraded the coke plant. Like Acme, this was an efficient operation with the latest, updates on older equipment, and a much newer Q-BOP operation and wire mill to the south.

Republic Steel (LTV) Chicago Works, 1981 – barge traffic along the Calumet River, Hullet unloaders, Ore and Coal Bridges.

Republic Steel (LTV) Chicago Works – blast furnace ore bridge and Hullet along the Calumet River.

Republic Steel, Coal Bridge, Hulett & Gas Holder – A Hullet unloads coal from a barge while the coal bridge distributes it in the yard. Huletts normally descend into the holds of ships to scoop iron ore, but these saw double duty as coal unloaders too. Because these huletts were used on coal barges we can view the operator guiding the rig just above the clamshell. In the background is a gas holder for the coke plant. The reason why these Chicago huletts hung on the longest by far of all huletts, was this situation with bringing up coal from the south on river barges, as opposed to iron ore boats that came in off the Great Lakes and had self-unloaders, which completely made hullets obsolete.

Republic’s Chicago mill was fairly unique in that its one blast furnace was small and it used two Q-BOP furnaces. But by far the standout feature of this mill was two of its larger pieces of equipment, the Hulett unloaders. When they were finally demolished in 2010, after having been shutdown since 2001, they were the last Huletts standing.

Republic Steel (LTV) Chicago Works – Hulett – notice the operator of the Hulett just above the clamshell. This site was the only place huletts were used on river barge traffic, since coal could be brought up by river from southern Illinois’ mines cheaply.

Republic Steel (LTV) Chicago Works – coal dock, Huletts, coal bridge and coal barges along the Calumet River in 1980. These huletts did double duty unloading coal and iron ore. This is the coal dock, the huletts would also move on tracks to the north end where the ore dock and blast furnace was located. Huletts were rarely used for barges, simply because they were a mostly Great Lakes phenomenon used to unload the holds of large lake freighters. In Chicago coal can came up on the river barges from the southern Illinois mines through a river/canal system and lake freighters can enter easily from Lake Michigan.

Republic (later LTV) and Interlake Steel (later Acme) were in the East Side neighborhood of South Chicago whose homes ran up to both mills’ property north and south, with both mills owning all access to the Calumet River for three milles.

INTERLAKE STEEL

Interlake Steel (Acme), Blast Furnaces “A” & “B” – Interlake’s (Acme) blast furnaces were on the east side of the Calumet River directly across from Wisconsin Steel. The basic oxygen furnace that received the molten iron from these furnaces was 13 miles south in Riverside Indiana and is still operational today. These furnaces, although nothing was wrong with them, and their basic oxygen plant was state of the art, would close for good in 2001, their demolition was complete by 2005. If they would have hung on until the Bush tariffs in 2004, they would have been in one of the most profitable years for steel mills in their history, peaking in 2006, and going to shit again in 2008.

Interlake Steel, Coke/Coal Conveyor Bridge in 1980. Here’s a rarity. The conveyors in this bridge brought coal from the coal docks on the east side, across the river and over Torrence Ave. on the west side of the river, where the Interlake coke plant would process it into coke and ship it back on the same conveyor, to be fed into the blast furnaces on the east side of the river. To the left is a brownhoist clamshell hoist, in 1980 this was completely obsolete, yet it functioned here until 2001 when it closed. By 2005 all structures were demolished.

Interlake Steel (Acme), Blast Furnaces “A” & “B” – Interlake’s (Acme) blast furnaces were on the east side of the Calumet River directly across from Wisconsin Steel. The basic oxygen furnace that received the molten iron from these furnaces was 13 miles south in Riverside Indiana and is still operational today. These furnaces, although nothing was wrong with them, and their basic oxygen plant was state of the art, would close for good in 2001, their demolition was complete by 2005. If they would have hung on until the Bush tariffs in 2004, they would have been in one of the most profitable years for steel mills in their history, peaking in 2006, and going to shit again in 2008.

Acme Steel started as the Federal Furnace in 1908. Originally located downriver in Riverdale, Acme bought the Interlake Steel’s hot end and coke plant 13 miles away in south Chicago on the Calumet River. In 1984 Acme spun-off from Interlake and would make high quality steel in one of the most advanced bof, caster and rolling mills in the world. It’s iron would come from the two furnaces 13 miles away on the Calumet in Chicago. These blast furnaces and the coke plant were permanently shutdown in 2001. The bof, caster and rolling mill in Riverdale were saved and sold to Arcelor Mittal in 2004, demonstrating how the remnants of the lost steel mills of Chicago, live on just beyond the city.

INLAND STEEL

Inland Steel Headquarters

Pushing further south into East Chicago Indiana there were two large integrated steel mills sitting at the mouth of the Indiana ship canal and directly across from one another. Arcelor Mittal had already bought Inland Steel and revived it, now it eyed the East Chicago LTV mill across the canal. LTV bought the Republic mill in its bankruptcy in 1984, now Arcelor Mittal would grab the LTV property in its bankruptcy (through ISG Steel) in 2004 and have two very large integrated steel mills under one name. And with the exception of the demolition of some World War II era blast furnaces, docks and coke plant, documented here, the old Inland plant is booming. The area has the most concentrated steel district in America and it’s in in full operation. Below is a series of shots depicting the old Inland Steel in operation in 1981:

Inland Steel, Plate Mill.

Inland Steel, Coke Plant.

Inland Steel would go on to survive and even prosper – so much, that Arcelor Mittal happily bought the place in the late nineties. Today it is fully functioning and enormously profitable, proving there is a way to be profitable over the long term in manufacturing in America, and quite a few foreign countries have bought and operate mills in America. Below is a section of the mill that was finally demolished in 2004 after being closed in 1991. The docks feature old brownhoists

Inland Steel & Republic Steel, Indiana Harbor Ship Canal. Inland had their own fleet of ore carriers. To the right of the ore boat are brownhoists, a pre-hulett technology.

Inland Steel, Docks, Brownhoists, Ore Bridge & Blast Furnaces – these furnaces, built for World War II steel production, were closed in 1992 and finally demolished in 2004. The brownhoist unloader to the left dates very far back, it was the technology that the hulett unloader replaced. As you scroll down you will see this area of the mill 22 years later, right before they were tore down by the mill and fed back in to the furnaces to make more steel.

Inland Steel, Indiana Harbor & Ship Canal, Dickey Ave. Lift Bridge – to the left, Republic’s East Chicago Works, to the right Inland Steel’s East Chicago Works. It was taken over by Arcelor Mittal who sold it all to Cleveland Cliffs in 2021.

Industry, particularly steel, defined the landscape here, and still does.

A RUST BELT RECURRENCE AND THE END OF THE STEEL MIILS OF SOUTH CHICAGO (2001-2004)

There’s more to a continuum and here’s what I found at the same mills that were shot 22 years previously:

Returning to see what was left of the Chicago Steel District in September, 2003 after a 22 year absence, was quite a hit, a lot like (and not softened by) many of those delivered since 1978. Acme Steel, formerly Interlake, and LTV Steel, formerly Republic, the last two mills on the Calumet River, in 2003, were now two years shut and weeks from the start of complete demolition.

ACME STEEL

Acme Steel, Blast Furnaces “A” & “B” – Acme (Interlake) Steel’s hot end in September, 2003 from one of the ore bridges. Interlake became Acme Steel in 1986 and shut for good in 2001.

Acme Steel, High Line – the high line is the area where all ingredients for iron production – iron ore, coke and limestone – are brought in on rail then loaded into the blast furnaces.

Acme Steel, Blast Furnace “B” Bell – all the ingredients for iron were loaded through the top of the furnace, and brought up by skip hoists in the white chute.

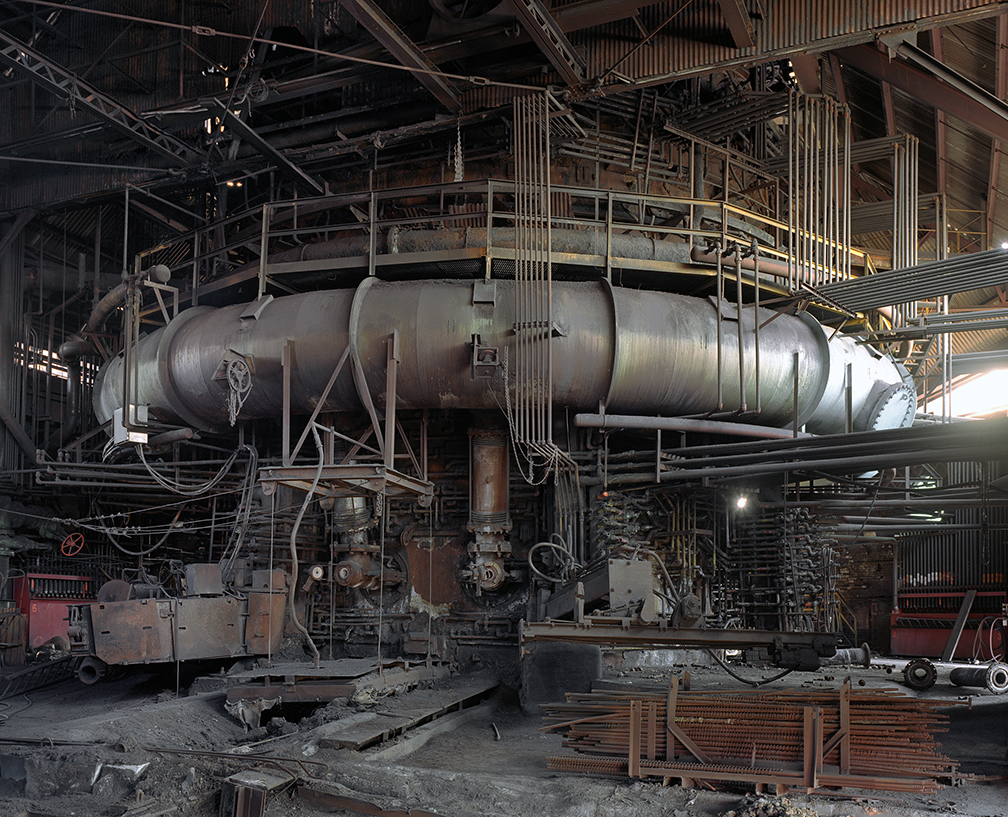

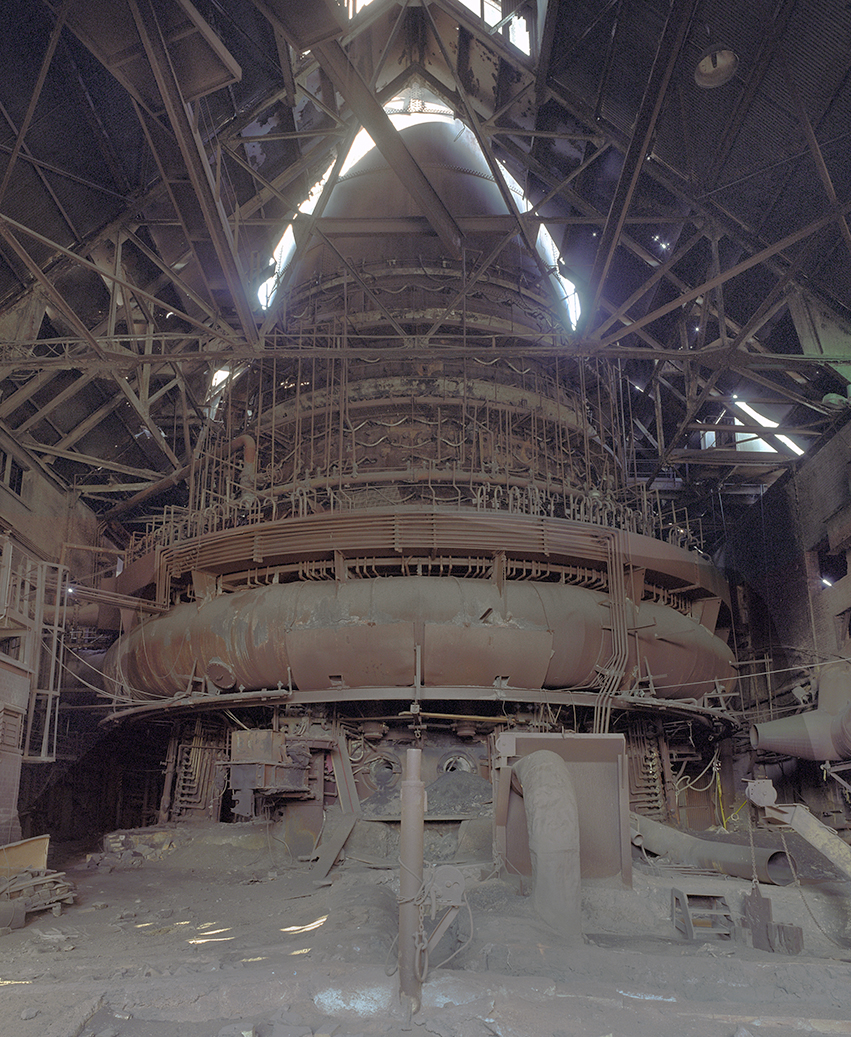

Acme Steel Blast Furnace “B” Cast House – here is where workers tapped the bottom of the blast furnace to release the new molten iron. When this mill closed in 2001, cast houses could be operated by only two men instead of a dozen in years past.

I wish I would have known that in September, 2003, when the two mills looked pretty much frozen in time, that a steel boom, sparked by protective tariffs would make the demolition very profitable, since scrap steel is heavily used in the basic oxygen plants. In 2003, whin i crossed the giant LTV scrap yard to gain access to two mills, it was filled with sorted scrap steel in huge proportions – beams, thick sheets. In the old wire mill and Q-BOP shop were piles of engine blocks, miles of scrap wire. I did two days of shooting, determining that December during the full moon would be the prime time for shooting, more darkness, more trespass, more cold, less security and mosquitoes. So I spent just two days shooting and took off. Big mistake.

When I returned in December, the Acme Steel blast furnaces, ore and coal yards were in full demolition. Its coke plant across the river on Torrence Ave. was in complete abandonment, as was the LTV coke plant and coal docks. The Acme coke plant was a goner, but the LTV coke plant, built in 1983 and updated was completely modern and efficient, and still up for sale. Just by virtue of the fact that a closed coke plant within a city’s limits is now officially considered a good thing by the local and federal government, let alone, the steel market, was probably enough to sink both the Acme and LTV coke plants.

But by December, 2003 the LTV scrap yard was picked entirely clean of scrap and so was the all the scrap stored in piles around the old wire mill and Q-BOP shops. Although LTV and Acme Steel in Chicago were done for, this empty yard meant that steel had rebounded in a very significant way, and the last two mills on the Calumet – modern, efficient, profitable as they were – couldn’t buy the time. Scrap steel combined with the molten iron from the blast furnaces, is fundamental to creating steel, and the empty yard meant that the price of steel was rising. So much so, that the new consolidated steel mills began feeding the old unused sections of their own mills and others back into their furnaces as scrap steel.

Acme Steel Blast Furnaces “A” & “B” – ninety minute exposure, 3:00 am, from a partially demolished ore bridge. A rare empty ore yard lies below, it would all be gone in a few more months.

Acme Steel, Blast Furnace “B” Demolition – ninety minute exposure, midnight, from one of the ore bridges. In 1991 as many as a dozen workers or more would typically run the cast house, years later, in some plants, only two workers would do the same work.

Blast Furnace “A” lit by mostly a full moon in a one hour exposure.

Flooded ore yard, coal and coke conveyors, with coal and ore bridges stretching south along the Calumet River.

Conveyor belt bridge over the Calumet River, flooded ore yard and brownhoist ore handling equipment.

Bleeder Stack.

Coke Ovens.

Quenching tower, water tank and chimneys.

Quenching tower entrance where,fiery hot coke fresh from the ovens would be sprayed with water.

Euclid grader lies abandoned on the far south end of the coke plant.

The steel mills continue past the Chicago city limits and into East Chicago Indiana where the old Inland Steel plant is still operational as an Arcelor Mittal plant. Arcelor Mittal also bought the old East Chicago works of LTV Steel across the ship canal,in the bankruptcies of 2001-2003, creating the largest steel mill landscape in America. Below are the remains of old section of hot end including two blast furnaces, a coke plant and docks. No where did i find a beter example of the year 2004 for steel, where facilities that had sat idle since the first Rust Belt closings were now being demolished since steel prices had risen to the point that using the obsolete sections of the mill as scrap, and feeding it back into the furnaces, became profitable.

ARCELOR MITTAL INDIANA HARBOR WORKS

Arcelor Mittal bought the old Inland Steel plant and, after the industrial recessions of 2001 and 204, decided to demolish any unused portions of the mill. There was an old abandoned hot end on the southwest end of the property and steel prices had jumped so high after the Bush tariffs that it was economically feasible to demolish the blast furnaces and recover the costs by melting all the scrap steel and iron in their own furnaces to make more steel out of it. In 2021 the mill was sold to Cleveland Cliffs and is still moperating very profitably.

Steel is the most recyclable material in the world.

Blast furnace “A” Bell.

Blast Furnace “B” Cast House.

Blast Furnace “A” Cast House.

Since 1978 the fortunes of heavy industries have been ruthlessly cyclical, but even by those standards, the 2004 steel turn around was singular, especially since it went up and through the roof after a swift annihilation in 2001. Of course, you always have another recession around the corner and the next one they would spell with a capitol “R” even though the recession of 1980 was worse, especially for industry, which never recovered, in a long beat-down.

There were exceptions to this long loss. 2004 was a critical time for American and European steel, as so much of it had gone into bankruptcy, but surprisingly things would immediately turn around. Finally catching a break, steel prices rose significantly just as American mills had gutted themselves and then quickly consolidated to take advantage of the best steel market since WWII. But too late for the last steel mills on the Calumet. There was nothing wrong with them. They were efficient and completely modern. They just couldn’t hang on long enough for the upturn.

The Former LTV East Chicago Works sold to Arcelor Mittal and now part of The Indiana Harbor Works. The basic oxygen plant that was originally built by Republic Steel, became LTV Steel and Arcelor gobbled it up on the cheap after the Big Shutdown of mainline steel firms in the 2001 recession. The waterway is the Indian Sanitary and Ship Canal, shot from the old blast furnaces of Inland Steel (Arcelor Mittal) across the canal. A flat region like Illinois relies on canals to link to major rivers but were also built to let what the city generated in waste float downstream.

Guards had spotted me in the afternoon, staked out my parked car and searched to find me. I waited until dark, and did this shot while trying to escape, which i eventuwlly did. The guard with my car got bored and just happened to cruise by me about 1000 feet form my car, which i walked quickly to, and sped off to a casino where my luck continued, winning 200 bucks on the quarter slots.

The history of American integrated steel making since the 1950s has been one of decline, so the consolidation of 2004 and boom in steel prices was atypical. Domestic steel was on the brink once more, but engineered a turnaround that is still playing out today as the gutting of overcapacity continues. The steel mills in Sparrow’s Point, MD, Warren, OH, Steubenville, OH, Mingo Junction, OH and Weirton West Virginia are being demolished right now. (they are featured in the books section under the title, steel)

That’s the background to these pictures and why the two distinct time periods – the beginning of the end in the booming Chicago Steel District in 1980 and, then, in late 2003 when the last two mills fell. These two time periods were significant for the life and death of the steel industry in the Southeast side of Chicago. March 27, 1980, when Wisconsin Steel closed throwing out 3,000 workers without notice, also had importance beyond Chicago’s Southeast Side. It was this sudden closure that, after Youngstown Sheet & Tube’s closure in 1977, made it clear that this Rust Belt thing that was going to last, maybe to the bitter end. By 2010 the long term consequences of what began in the seventies had finally come and gone.

LTV STEEL CHICAGO WORKS

LTV Chicago, Coke Plant Conveyors.

LTV Chicago, Coke Plant Push Car and Pusher.

LTV Chicago, flooded coal yard and coal bridge, Acme Steel is framed under the bridge and the LTV coke plant is to the right.

LTV Chicago, Ore and Coal Yard and Bridge.

I’ve seen and shot lot of abandoned industry and never enjoyed it. Operational industry is the antidote – loud, smelly and on fire with lots of workers. That’s how I remembered the old Chicago Steel District, prior to seeing it in 2003. While first shooting the mills in 1980, i’m not sure if it ever occurred to me that, 22 years later, I would walk all over them, and for all the wrong reasons. Shooting the huletts in close detail, or the inside of the blast furnace cast house, particularly months from its disappearance, and, after having shot it all operational, has its importance, but the fact that there was nothing intrinsically wrong with them, and they had willfully fallen on the sword of self-sacrifice for 25 years, to become leaner and better, but it was only temporary global market conditions that finally did them in.

LTV Chicago, Hulett Unloaders along the Calumet River.

LTV Chicago, Hulett Unloader – Operator’s Cab.

LTV Chicago, Hulett Unloader, 3:00 am in a one hour time exposure.

LTV Chicago, Hulett Unloader.

Chicago LTV, Hulett Unloader, Wheels.

LTV Steel Chicago, the former Republic Mill sits permanently idled three years after its closing. The coal bridge and huletts would last for some years, until finally sold as scrap in 2010.

END

The four neighborhoods in Chicago’s old steel district were born rough, out of an extreme environment, even by the standards of of an industrial-age city. I was remembering this while guarding my camera during a ninety minute time-exposure, from a very high position on the partially demolished ore bridges in Acme Steel at 3:00 am in December, 2003. The unusual stillness now was quietter than it had been for 150 years. It was only interrupted by some gunfire from South Deering. Nothing compared to the explosive energy of the mills in their heyday and their effect on all the senses. Loud, smelly, noxious, glowing and lighting the night sky and surrounding city neighborhood with its molten metal.

Republic Steel’s Chicago operations along the Calumet River in 1980, that became LTV Steel in 1986 – coal barges pass each other before huletts, ore and coal bridges, coke plant and blast furnace.

STEEL ON FILM

It stands to reason that when places lived in, or experienced no longer function they become abandoned, when its demolished, it disappears. Ruins are visited, admired for their disconnected ambience and connection to art history, but little else. Disappearance and abandonment, not ruins, implies you knew what was there to begin with. The physical continuum, remains tied to the inside, while ruins, at best, ties itself to the something outside the subject, like the official history of art.

Generally the patina hounds seemed to have missed Chicago’s steel district. I couldn’t forget it after having lived there and been involved with the mills. When I learned of their condition in 2003 it became necessary to go back.

Certainly there are always professionals, who don’t confine themselves to only a story of ruin. Harold Finster always knew the time, so does John Bartelstone, and, with regards to steel, particularly in East Chicago, David Plowden was right there and a lot of other places, and look at Viktor Macha.

Thirty-five years ago, art photography and journalism usually looked at the steel industry, with black and white film. Journalism and documentary made the mills gritty and real while art photographers shot in large format sticking with black and white. The big exception in all this is Charles Cushman who shot 35mm Kodachrome as far back as the thirties, and some others like Frank Delano who shot large format Kodachrome in the FSA.

I shot mills in both 35mm black and white and color for a year or two when I first began taking pictures seriously, then went strictly color. By the time i began shooting Chicago mills, I was well into only color. It was as a natural fit. Color was far less abstract, (arty) and 35mm Kodachrome 25 was grainless, yet certainly real. I would hit the mills with some hard light, and I couldn’t help but think I was shooting these industries, in their survival mode, at the birth of the Rust Belt, like National Geographic or on a commercial assignment for the mill itself, not a eulogy for its coming demise, or, at least trying to make something that you felt was going away be presented as something great in its time, not just dirty and dismal, particularly in black and white.

The Lost Steel Mills of Chicago (a.k.a., Chicago Forgets Where It Comes From) in operation, decline and ruin is the method, long term. The ruins crowd of art or internet-pop culture neutered their own genre’s ability to create impact by sealing itself in a fetish of effigial convolution. The whole endeavor’s mannered ambience or connection to the Official History of Art, is all it has going.

There’s no other city that defined itself more by labor history, than Chicago. Laboring myself for long times in some cities, one, in particular, even more blue-collar than the old Chicago. But after rubbing shoulders with Chicago, i realized i never knew such appreciation for labor history existed. And make no mistake about it, the factories of Chicago were huge and widespread, and did result in the city’s great growth years, as it did in so many cities, so the impact and reasons were all there. When i lived there many neighborhoods were still dominated by large factories. Strolling through the streets, even at after midnight, these plants were open, lit and making noise from the third shift. Walking by them and all the bars, or the old neon-lit movie palaces showing features for a couple bucks, was right near the end of working-class neighborhoods being desirable places to live, just before they became the working poor, if they stuck around for the cashier-type wages that would be the only employment as guns and drugs proliferated as the quickest, easiest and biggest source of dough in the old hard-working, nice wages paradise that was once, to my way of thinking, beautiful.

Does it matter today here in this city? I guess as much or little as everywhere else. This was the city of Royko and Terkel, Algren and Bellow, but why mention this nice bunch of Chicago writers that got to die living out their creed, and not have to suffer the indignities of the digital age? Things move quickly, and disapper and that history, like its old voices, is it alive? To base the answer on the difference in the Southeast Side’s steel industry, many years apart, isn’t fair at all. It’s just what one thinks about now that the steel mills of Chicago are so many years lost, or when i get calls to use my pictures of lost Chicago industry before i can, myself, publish them. This has been unpublished in my archive forty years. Or when i see this ruins exploration stuff whose texts are regurgitations and edits of internet knowledge and the already found, and whose pictures attach themselves possibly to art, and not multiple concerns simultaneously in order to go beyond fetish. Concerns such as history, particularly social and labor history, and, the most important – experience. Because “La expereincia es la differencia.”

It is at these times that i am reminded that forty years have passed since i shot there.

The citizens who waved the flag of the broad-shouldered city of the working-class for so long, and are still alive, moved on, i guess, like so many who hooked up with the working-class for their movies and books for so long, only to go, and find other causes that they also do not have a living link to.

While some don’t really work that way.