There’s nothing like shooting the industrial west. All the advantages of the western landscape can easily be put to work, without nature as the subject, but as the setting. Even when I shot a book of all the American badlands by moonlight in the nineties1990s, I would try to also hit the nearby industrial sites which could be captured in the same light because of a lack of artificial lighting where indiustry is set out there. Even in Butte, whose headframes and mines were on higher ground above the city, particularly up towards Walkerville, it was possible to get a fully lit landscape with simple moonlight, and with the continental divide as a backdrop, it was so clear it wasn’t funny.

One trip to Montana began by way of Oregon, and the Columbia River, where a guy I grew up with had settled. The Columbia has many hydroelectric facilities, along with infrastructure like power lines, emerging from the dams and traveling over the high plains. I shot the transmission towers by moonlight, just above and close by the dams, in wheat fields that positively hummed with power, and when I would set my metal tripod on the hood of the vehicle and it would become electrified. This was nothing like when I had been shooting power lines by moonlight, but far from their source of generation, which was usually a single power plant, and not a water driven dynamo a mile or two away.

That tremendous growth of American infrastructure projects from the 1920s to the sixties, ending with the interstate highway construction, looks puny compared to the Chinese growth of the last twenty five years including the top seven longest bridges in the world, dams, canals, airports, rail, highways, you name it, and the original makers of large infrastructure projects like the Great Wall, cannot be beat, particularly when it comes to scale.

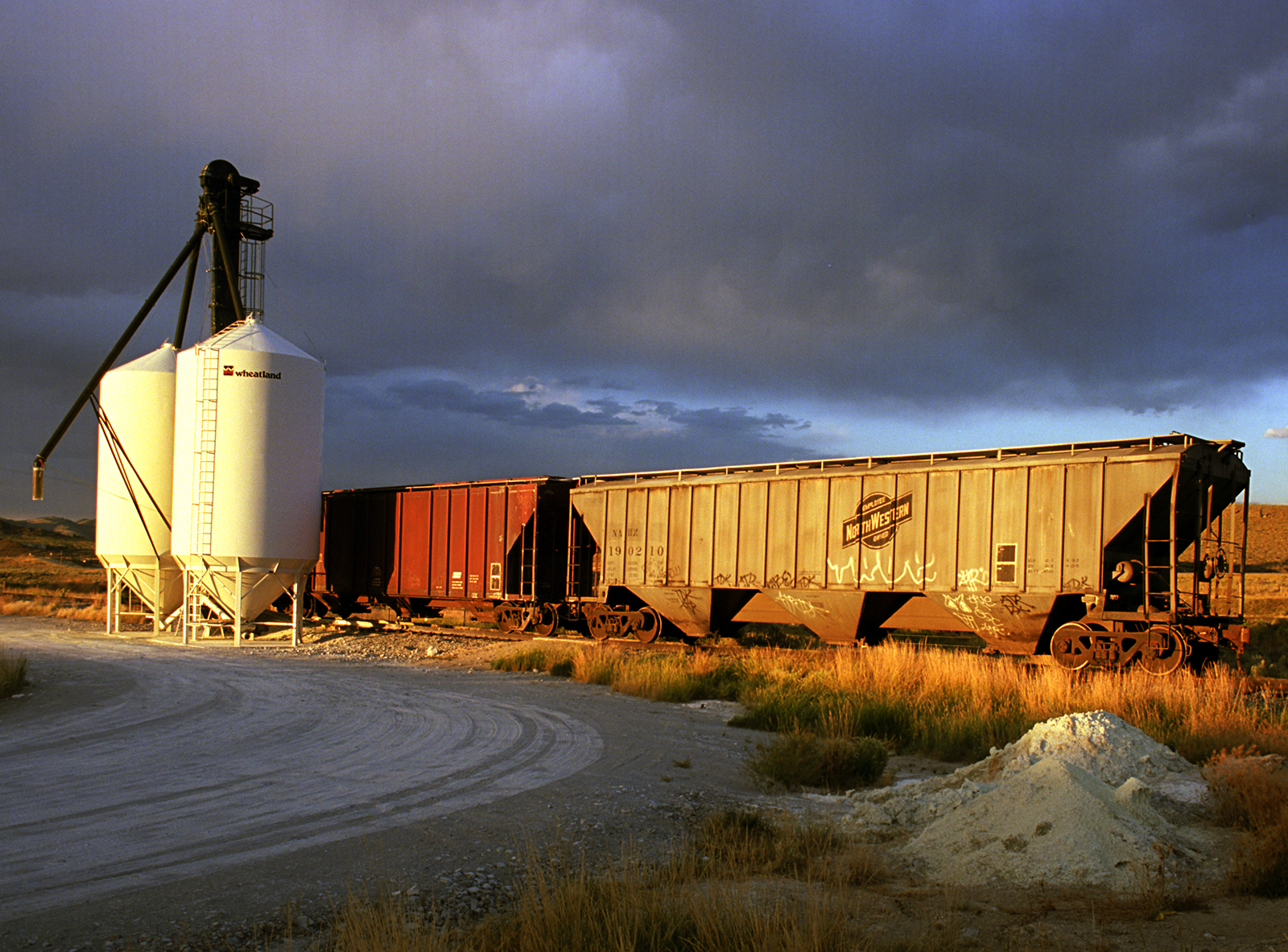

Setting up plants next to or above where resources are extracted is a mainstay in these vast, high landscapes, as is, shipping resources out by rail to neighboring cities and towns and even to the West Coast for delivery to Asia. A lot of times a camp grew into a town, then a city, and, if it got big enough, when the original industries died off, it hung on, then flourished years later. And others became ghost towns at best. Montana was historically, with agriculture and industry, boom and bust. Tourism might be different but things like covid can change all that.

A moonlit long exposure of a pumpjack inside the Salt Creek Oil Field in central Wyoming. If i was shooting badlands by moonlight, i could, on the fourth night, shoot industry, and with no artificial light, moon light works fine.

This place is known for its size, reserves, history, especially being at the center of the Teapot Dome scandal. Today and for along time now pumpjack technology is obsolete, fracking having taken over, and Wyoming going back to 2000, was a leader and early proponet for fracking.

When in Montana, from the first time i went there, i shoot, primarily, its industries of mining, metals, power plants, railroads, energy production, refining, lumber and agriculture, mostly wheat and cattle.

The landscape for locals who live and work here is known for endless fields of wheat, cattle ranching, smokestacks, grain elevators, open pits, strip mining, rail lines, fences, silos and coal-fired power plants, while the state’s other big industry – tourism – handles the natural wonders, that still need airports, highways, bridges, gas and food to run on.

On the high plains and mountains it began with the buffalo, and, by the time that resource was eliminated, the cattle came, first in a free range migration, followed by agri-business and industrial-scale farming. Ironically buffalo have become part of the draw, along with many animals, in the state’s many parks and hunting grounds.

Niether the geography of racism, nor environmental racism, would be something I’m interested in, because, what i presume those euphemisms are saying is what i know by heart and mind already, and what I know doesn’t begin with me and, although I love the drone perspective, it’s far more sensual on earth. I’m not kidding, the drone perspective is really something, free of the weight of earth, and going place no photographer could go.

In the case of Montana, and the intermountain west, basically in a very big and obvious way, it’s the whitest place. Naturally, any industrial neighborhoods and towns, will have problems associated with chemicals, toxins, smoke and polluted water, but i can’t really call those places any other thing than what it is, was and will be, poor, working-class, even middle-class neighborhoods that are nestled into industrial zones in towns and cities who actually got their starts as such by virtue of industry designed to extract natural resources, mill and refine them, into products, that, for one hundred years wer formed locally, like the oil industry has become, once more, with fracking and loose regulations.

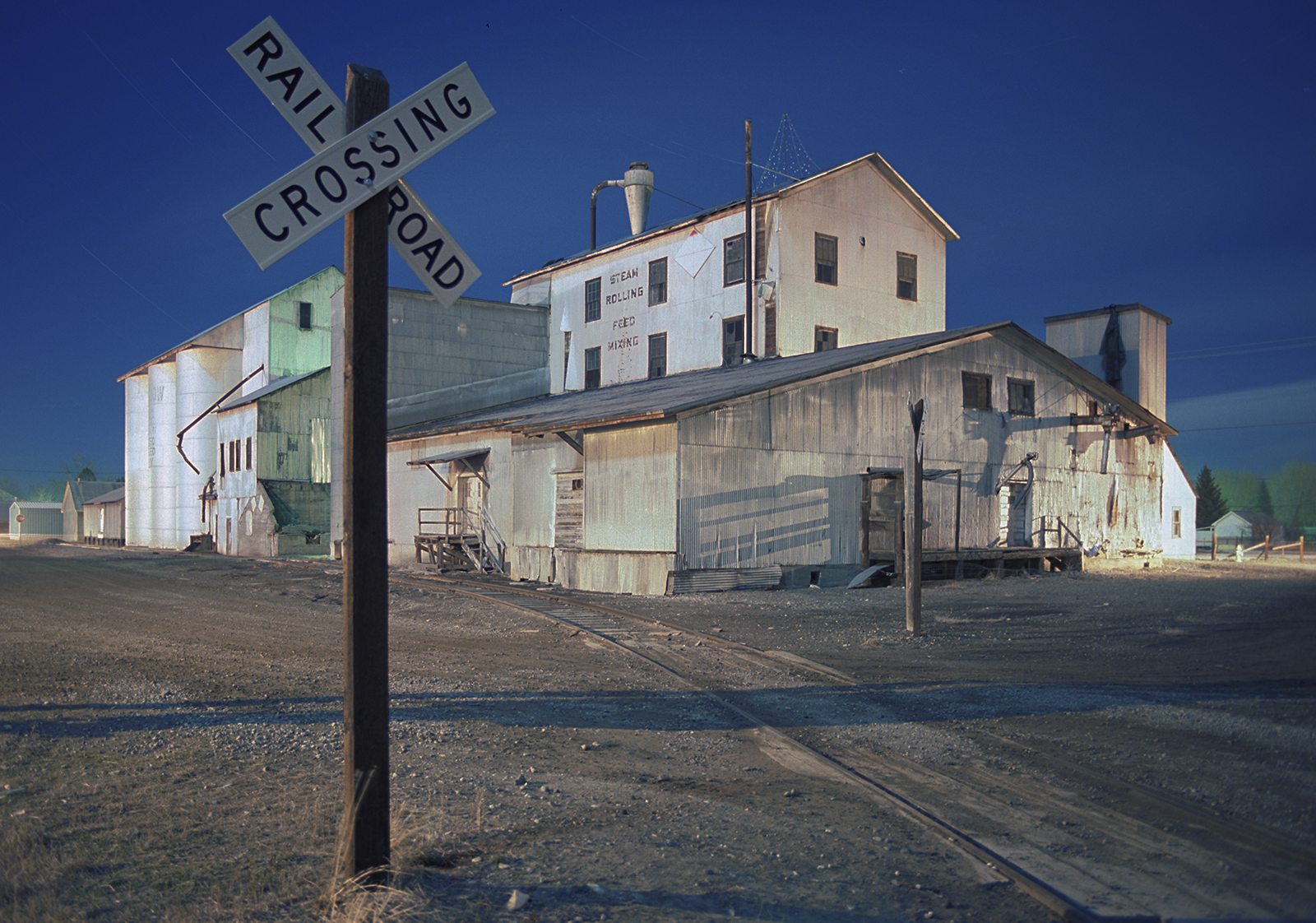

In these western states, beginning with agriculture, the railroads opened up the state for the development of towns and industries, including tourism connected to the state’s towering mountain ranges. Smokestacks, grain elevators and the headframes are the man-made towers that dot the Montana landscape, and, are, in fact, seen as landmarks of the state itself, at least for locals.

I mentioned a good friend that I grew up with who settled on the west coast, but traveled as a salesman all over the west, which allowed us to meet and do our work. He would swap out the advertising he was selling for a room at a motel and meals at a local restaurant, in Montana, that would be a supper club. We did this in 1989 and 1995 and with his brother coming from the east in 1998, not to mention all the solo shoots I did to Butte, Anaconda, Laurel, Billings, Great Falls and all the towns in between, that became what they are through industrial boom and bust cycles that finally halted in the great downturn of the early 1980s that began to let up ten years later, and, now, into the fracking years and newer technologies, the state has moved far from those years, a long time ago.

The Bell Diamond headframe – left shot was November, 1989, right shot was September, 1998. Being so high in elevation, and well above the city of Butte, the Bell Diamond could catch both last light or moonlight as seen here in 1989 and 1998.

In the 1980s the headframes of Butte, were, in fact, my introduction to heavy industry in Montana, and the perfect example of a city on a hill, a very rich one, that was defined and funded by what lied below it and could be extracted. This place was so ideally suited to what I had been doing for years, it wasn’t funny, and ended up doing a book about it over the years. And already being a transportation hub, the Butte area – Silver Bow County – attracted more industry, like the canola refining plant out by Rocker, now gone, and as part of the foreign trade zone FTZ #274.

When I stayed in Butte in the 80s it was right after everything shut down. There was always copper and other metals visible in the drinking water and the bath water. It was the way it was. At this time everything in uptown Butte was dirt and rock because nothing would grow. Part of the east side of downtown and a couple of residential neighborhoods had been replaced willfully by an open pit mine, that, after its closing filled with water that became toxic, laden with heavy metals. Eventually the richest hill on earth with America’s biggest copper deposits became the largest Superfund site in America, as well as the city and many neighborhoods entwined in it.

It’s not unusual to have a mining camp so high in the mountains even above timberline. But Butte was a city that grew to the state’s biggest, and was far north in the Rockies sitting right on the continental divide. It was loaded with heavy industry and an immigrant population that made it seem like Brooklyn-on-the-divide. The entire city was there because of what was beneath it, and that defined it, until the end of mining in the 80s. As a result both industry and neighborhoods mixed together, so much so, that large portions of downtown and adjacent neighborhoods were gobbled up when open pit mining began in the 1950s. And there was little protest. When I first landed there, and took a look at it, it reminded me of where I came from, Brooklyn. It had great architecture, a geography providing great vistas of industry, and railroads sneaking through every neighborhood, a beautiful downtown that was called uptown that was, of course, right there in the mining district.And already being a transportation hub, the Butte area – Silver Bow County – attracted more industry, like the canola refining plant out by Rocker, now gone, and as part of the foreign trade zone FTZ #274. There are two others in the sate – Great Falls FTZ #88 and Toole County FTZ #187. Today REC Silicon has a plant in the Butte FTZ where they refine the raw materials, silica, to great purity, and sells it for use in electronic screens, displays and hybrid vehicles.

The Canola Refinery west of Butte in the foreign trade zone, 1989. The plant is no longer there but other manufacturing has arrived.

The Canola Refinery in 1989.

Another place, more modern, that rose from the resources underneath it, is Colstrip, that had huge power plants to burn its coal for electricity. Combined, all of the units burn an average of 9.2 million tons of coal a day to create 2,094 megawatts of electricity: enough power for 132,000 homes. A 500,000-volt transmission system carries power from the four Colstrip units to customers in the Pacific Northwest. The lines stretch 497 miles through Montana. With an estimated 120 billion tons, or 25.4 percent of the country’s total, Montana has more coal reserves than any other state in America. The principal coal deposit lies in the Rosebud seam, a 24-foot-thick layer of coal that sits about 100 feet underground.

In the seventies the federal government recommended the building of another 20 strip mine/power plant facilities in the state after the “success” of the Colstrip plant. It’s pretty handy. The state is promoted as a pristine natural place that is, like America was, when you didn’t even lock your doors. Meanwhile the state itself has found itself, historically, more in the grip of the industries that employ locals and define towns whose only connection to civilization was, at one time, simply to be connected to railroads, which could bring things in and take things out, and, eventually spur growth in towns along its path.

The Purina Grain Elavators in Great Falls.

Like Butte and Anaconda, Great Falls was a major industrial city that had a large oil refinery, huge copper smelter, hydroelectric dams, railyards and grain storage and transfer facilities. Across the Missouri River in the neighborhood of Black Eagle was the Anaconda smelter with its 503 foot smokestack and the smelter. The neighborhood was nicknamed Little Chicago for its many bars, clubs and restaurants.

The Ryan Dam at one of the Great Falls of the Missouri River. Whether industry or homes hydro has always been a big feature of the Montana landscape, and in the vicinity of Great Falls there is the Ryan, Rainbow, Black Eagle, Moroney and the Cochrane dams that appear here on the Missouri. A dam further upriver was built to power the Anaconds Works of Great Falls.

Black Eagle Dam is the first hydro project in the state, built in 1890 and replaced, but still in operation. All these early dams helped give the city its nickname – The Electric City.

At Great Falls Montana they celebrated the smelter. An area behind the facility had gardens, fountains and some beautiful buildings, and it beautifully framed the smokestack that actually spewed all the accumulated smoke, dust and metals from the various smelting processes, such as cadmium, lead, arsenic, mercury and sulphur.

But all in Great Falls, near and far from the smelter, loved their stack as a symbol of the city that began because of and at the same time the plant was built. People sung songs in honor of the 502 foot chimney. The unincorporated neighborhood next to it, Black Eagle, was a well loved, hard partying, club, restaurant and bar scene with an accompanying shanty district, where folks had to be forcibly removed for expansion by Anaconda. Can you imagine what Black Eagle was like before the closing of the smelter? Malmstrom Air Base, just miles away, had a place for its people to go, as did the the city natives of Great Falls, and local teenagers getting into the bars as well. In a state known for boxing and bar fights, the mix of military, blue-collar workers from the smelter and refinery, young people and locals from throughout the county, can you imagine the action? Black Eagle the nest of nightclubs and residences across the river from town, out by the smelter and the refinery.

The Refinery in the Black Eagle neighborhood, the industrial center of Great Falls. Just to the south was the Anaconda Works with its 503 foot smokestack, now gone, but never in the memory of the entire county.

And the folks of Great Falls loved their air base, forcing the government to name it after a WW II vet who was captured, but died nine years later at Malmstorm while testing aircraft in 1954. He loved Great Falls and the the town loved him back.

The Harvest States Coop Grain Elevator is in the background, with steel silos to the right, next to the rail tracks, and a golf course sits off to the left, in Great Falls, just outside of the Black Eagle neighborhood.

Drive north out of Great Falls, a rail, oil and grain shipment center, along U.S. Route 87 and you will parallel the railroad for much of the way, as well as, the Missouri River, the three basic modes of transportation in the state, until airlines – roads, rivers and rails. Fort Benton was the jumping off point for people that came up the Missouri, and the fort became a town, where steamers could go no further upstream. Traveling to Havre itself a railroad town, from Great Falls, the grain elevators show up about every thirty miles – Fort Benton, Carter, Loma, Big Sandy and, only Box Elder has no grain shipping infrastructure. Around Fort Benton, near the Missouri River the terrain is hilly high plains grasslands that will flatten out into the classic big sky prairie punctuated with small badlands and great stretches of wheat, irrigation, agriculture and just plain nuthin.

Modern grain elevators in Carter, 1995.

A freight train run towards the grain elevators of Fort Benton, 1995.

Old wooden grain elevators at Loma, 1995.

Environmental racism is identity politics which has itself as the starting point. A more catholic view invites all, realizing differences. Poor folks have always lived close to industry where it’s cheap, if unhealthy. People lived in these neighborhoods to walk to their jobs in industry. When the industry leaves then people get stuck. The value of housing plummets and folks get stranded more. If anyone new shows up it’s simply because it’s the cheapest part of town to live in. But in many towns when the mills were operating it was a good place to do business and live. Granted in all these towns the more income and the further you are away from the factories and the higher you were above them. That’s true everywhere.

Billings, the state’s biggest city, at a population that Butte reached and surpassed 100 years ago, and, unlike Butte, is a more modern place, having boomed in the fifties through eighties. It still has two large operational oil refineries – Exxon and, Phillips 66 which was Conoco when i shot it in 1989.

The Yellowstone River, Conoco Refinery and downtown Billings in 1989. Out on the other side of the valley on top of the northern rimrocks is the airport, and below it the suburbs of Billings.

It’s the state’s largest city at a population of a 110,000, that was Butte’s population in 1910, when it was like Brooklyn on the continetal divide. Today the population of Butte is 35,000.

Billings, from above the Yellowstone River on Sacrifice Cliffs looking north where the airport sits on the opposite rim of the valley. The bottom shot includes a power generating station that is, of course, powered by fossil fuels.

The Conoco Plant in the downtown area is adjacent to the Yellowstone River and Interstate 90 while a residential neighborhood lines the north side which would be considered “the other side of the tracks” from central Billings. A completely mixed neighborhood, of generally poor and working-class, with some nice homes as well. Further inward is the old skid row, literally next to the railroad tracks from downtown, and this area is now even gentrifying.

The Conoco refinery, downtown Billings, 1989.

The Exxon refinery is further to the east into Billings Heights with the same configuration – the refinery is between the Yellowstone to the south and residential neighborhoods to the north. Here it’s a very nice, middle-class place with the look of a seventies suburb.

The Exon refinery, Billings Heights, 1989. The facility is still in operation, utilizing local oil from the Bakken, as well as, Canadian crude.

Just west of Billings, is another refinery and rail town, Laurel, whose railyard is one of the west’s biggest, now run by Montana Rail Link. Cenex Harvest States is still running the refinery which was built in 1930. The Billings canal begins in Laurel and provides irrigation. The town was a place where the Lewis and Clark expedition stopped, for a reason.

The Cenex Harvest States Refinery, Laurel, 1989. I never ran into a town or city in Montana whose people didn’t love their industry.

I mentioned that sometimes i would sync shoots with my best friend, who worked the northwestern states, as well as, his brother who would come in from the east to meet up. Their family was from Johnstown, Pennsylvania, one of America’s great isolated industrial cities in the Appalachians and was seriously filled with great bars and the Bethlehem Steel Plant. I remember Ray, my best freind, another friend, Craig and I worked at a precast concrete plant on the high plains of Colorado in 1971. We lived in a mobile home we rented. Next door was an egg farm where they sold eggs at wholesale prices. We ate a lot of eggs. The job was a pain in the ass, and we were really happy to have work and be able to head into town or cruise into the mountains to the west.

I’ve never heard a Montanan complaining of the state’s industry – the way it looks or smells. I guess it’s a reverse politicization, from the perspective of complaining rust belt cities or east and west coast cities, or it’s because i only spend time in places such as these. In Montana there is abundant oxygen, and nature is always just a short drive away, and, just like all the working people, their job and its wages are neded to breathe Montana air and see Montana natural wonders. Work, that’s how i first got there, as well – on a job. Which reminds me of the times in 1971 when my best friend, Ray, and another friend, Craig and I worked at a preccast concrete plant out along a state highway on the Colorado high plains

Following the highway and rail lines further west on the way to Butte, and cross by the historic towns of Manhattan and Three Forks, both of which, have grown with agri-business and industry.

Manhattan, originally called Hamilton, then Moreland, was renamed when a group of New Yorkers decided to get into the malt barley business. The town originated because Dutch settlers, who were experts in irrigation and barley production, made the Gallatin Valley into a prime malt barley producer. The Manhattan company built the grain elevators, and the store and sold most of their malt barley to east coast brewers and some to Montana breweries who still got theirs through other sellers in the Gallatin Valley.

Manhattan Montana was known as a center for growing malting barley, particularly the Manhattan Malting Company, that shipped much of its production to east coast breweries, while Montana brewers still got theirs from the same region. With a rail spur, Manhattan became the place to ship the barley by rail and grain storage tanks, silos and bins were built along the railroad line. Teslow, the renowned grain elevator operator in Montana took over the storage and transfer facilities, that are now gone, and, I shot the Teslows back in the 1980s by the light of a full moon in long exposures. The same in Three Forks with its grain silos that are Teslow branded, beat up, but still in existence today.

Teslow facilities in Manhattan, 1989. All the Teslow shots were done with using light from a full moon in one hour long exposure on film, when no one was resally doing this kinsd of lighting, because of its difficulty with film and reciprocity and extreme color shifts, untio digital came along and made it really easy.

Later, Walter Teslow would buy up grain elevators throughout Montana beginning in 1958, eventually amassing seventeen facilities, including the ones that were left in Manhattan after its boom, as well as, the Livingston Elevator, that, through its preservation campaign, made the name of Teslow famous, but took all the attention from his many other elevators that have bit the dust, including the structures in Manhattan. Still, nine miles west in Three Forks a classic Teslow structure is still standing.

I got a chance to shoot the the Three Forks Teslow facility at the convergence of some time, place and better technicals. The late eighties was the start of the final Golden Age of Color Photography, and, it began for myself, by not shooting Kodachrome 25, but a new color negative film with the same iso and high resolution, but could handle color shifts and greatly reduce the reciprocity factor when shooting ultra-long exposures by moonlight. I was still seeing what the film could do, when I shot it in two different full moon months, at the Teslow elevators in Three Forks. Today digital has made this easy, and, thus, popular.

Another Three Forks industrial site is the talc mill now owned by Imerys Talc America, that recently folded because their talc was contaminated with asbestos and people sued. It was the largest talc plant in America. Talc is the softest mineral known, and, unfortunately it can occur along with asbestos in certain areas.

Just seven miles north of Three Forks is the company town of Trident that just missed being called Cementville. Although there isn’t much left of the town, all the houses are gone, and the concrete paved streets are still there, as is the cement plant that still operational today, and another example of extracting, milling and refining resources on sites that mine them, and here it is the limestone used for cement production.

Trident’s train depot was saved from demolition in 2012 and was moved to Three Forks. Montana Rail Link still runs trains through town, but the last passenger train stopped long ago and the last resident left in 1996. No one disliked living there. The company rented the homes cheaply, there was a post office, the railroad had a station, and the Missouri River was there for relaxing, fishing and swimming. The cement plant with a benched limestone quarry was a short walk away. With Three Forks just seven miles away people must have preferred life in Trident. Relatively speaking even the small towns and tiny enclaves, of Montana had their own industrial landscapes. A place as small as Three Forks had grain elevators, and an important talc plant, and not far north at the cement plant in Trident, there was a tiny company town along the Missouri River, just miles from its beginnings at its three forks.

Trident, 1989. It’s now called the GCC Trident Plant (Grupo Cementos de Chihuahua ) another Montana and American presence by a foreign company that makes a profit and does well, when American companies are not interested.

Fracking completely changed the supply of oil and natural gas, making Montana’s coal reserves, the largest in America, lose value and a domestic market. Montana’s refineries, being fed Bakken and Canadian oil now, are doing fine. The five existent facilities produce much more than the thirty-one refineries that were built in the heyday of the state’s early oil booms.

Copper ore is shipped overseas from the Butte mines, but here and in Anaconda, Helena and Great Falls, the smelters and refiners for the metal are gone. Metals like palladium are big players today, and gold has always been mined here. Between Three Forks and Butte the open pit of the Golden Sunshine Mine can be seen, providing good jobs to another Montana town, Whitehall, tracing its existence to the railroad and what that meant for the region’s resources, like gold, silver, palladium, copper, zinc, talc, cattle, wheat and barley.

Today, in America, the importance of large infrastructure projects to foster growth and trade is a lost cause to the information highways accessing different, far more immediate and profitable resources. But infrastructure here on earth, instead of space, the moon and mars, can have the most immediate and direct impact on lives that are lived locally. Some of whom live high up in the north, isolated in a vast sea of land and sky where you can still get away from too many people. Who needs to go to another planet, living in Montana? It’s the geography, the weather and the isolation, and, for some, the industry set in a vast natural landscape.

For forty years our technical achievements, for instance in electric and autonomous transportation, outpaces exponetially the infrastructure meant to carry it, which is outrageous and human – to go for the quick big profits by making technical dreams come true, or, at least, have a tech company with no profits, losing money, but valued into the many billions. When What’s App was sold to Facebook for 19 billlion, it had nineteen employees. Cleveland Cliffs bought all the steel mills of Arcelor Mittal, the most in America, for 1.4 billion in 2020. Cliffs employs 25,000 people.

Links about Montana industry.