“Old seltzer men never die — they just lose their spritzer.” – Eli Miller

As much as I want to deny it, there it is. It’s true, and that’s basically what happens to us all. How do you know if something is true?

It’s the art of picking something up, putting it in a truck, transporting it and carrying it to its destination. Basic human labor is the most honest work especially with these guys who possess humor, integrity and smarts, and, clearly, like many laboring folks have what it takes, then, to be anything, but for their own reasons go with a physically hard job, whose psychological benefit is working out any negativity on the job, and getting a large volume of blood and nutrients to circulate and aid in the production of BDNF.

These Brooklyn seltzer men had no visible vices, unlike many blue-collar folks where that type of work is synonymous with drinking, smoking and general pain alleviation and psychological release from aches and drudgery. Not with these guys, who, as business men, knew they were essential workers before a pandemic reminded us about such a thing.

Seltzer got its start when Joseph Priestley invented carbonated water, by accident, in 1767, and it soon became popular in Europe. The siphon was invented by Deleuze and Dutillet in 1829, and by the 1880s bottled siphon seltzer was a staple, especially in the 1920s and 1930s, forever associated with the the Three Stooges and Hollywood, just before the introduction of the commercial soda market after 1945, when it severely declined in demand.

In the seventies a group of young, appreciative and energetic Jewish New Yorkers revived the business. In 1989 I worked for one of those companies, although it had changed hands by that time – the founder moved back to Israel and a Hasidim gentleman, had taken it over.

There was Marty and a few others which, in Manhattan especially, revived a business in dormancy.

ELI MILLER – SELTZER MAN

Eli Miller died in 2017 and was one of the remaining New York seltzer men, and, is distinguished as perhaps the longest running. The internet has many articles about Eli, and, if you check them, you’ll see why he is such a symbol of the not fading, it already has, business of old seltzer. Although, all the remaining seltzer guys, such as Walter Backerman or Ronnie Bieberman, fits this bill as well, and Walter’s own father, like Eli, was a seltzer guy, and, like all the guys, had that inborn love for seltzer, its history and its place in keeping whole families supported and healthy.

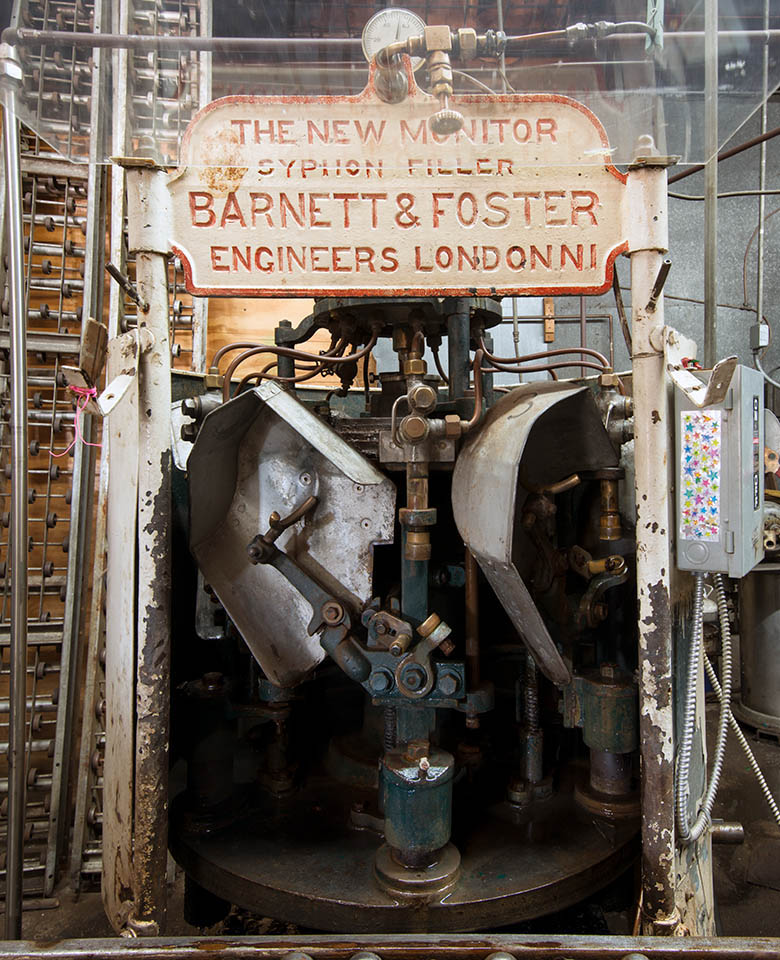

Independent contractors and business people, not hourly employees, these guys own their bottles and their trucks. The remarkable and historic Gomberg facility stores and fills the bottles with the real seltzer produced wholly on site with machines dating back to the 1890s, that themselves, are a work of art.

There is a lot of information and stories about Eli on the internet. As a former seltzer man I’ll add some source material that might give you an appreciation of the years Eli spent on the streets delivering seltzer, and, of course, the pictures. For Eli it was about his customers, and his friendly relationships with them. Obviously many folks loved Eli for who he was, and combined with his own friendly, winning charm, it was a two-way street. No one can fake that.

Eli used to tell me a lot of stories about the folks on his routes through the years. I forgot most of them, I’m sure many are, in fact, on the web, please take a look. Writing, at the age of 68, I work on and want my memory to stay in tact. I hung around Eli in 2013 when he was 82 and his mind was very sharp, and on a labor level, I can understand how seltzer slinging for a life would aide the mental part of our bodies. Like seltzer work, experience is rare, and should be valued since it’s disappearing, and by virtue of experience, this work would keep you fit and very alert, largely because your heart pumped so intensely, by the time you got home, took a shower, you were sore, but very alive, completely refreshed. I guess that’s what a gym membership buys. It’s funny in the blue-collar end of things, most guys at this moment of clarity, want to get high, drink and become dazed.

Culturally, it wasn’t there for the Brooklyn seltzer men. As naturally smart Jews i’m sure this played into this.

To have this type of job and retire at the age of sixty-five is pretty incredible, but to have your father die of a heart attack on the route, and then to do the job yourself until the age of 84, is more uncommon than being a seltzer man in 2020. He survived two more years. The route sustained him, but the body gave out, then he didn’t have the route. When a person lives alone, and especially when older and many friends are gone, a type of work where you are genuinely wanted and even necessary to people, as well as, the social dimension, of dealing with your customers, many very long term.

Furthermore, and only speculating, Eli’s route was like a living memorial to his father, walking in his footsteps every day, and, as the Times said in its obit, he was indeed a sultan of the beverage, although, I would say Eli was more qualified as to be called, The Man, that is to say, Minutus Carborata Hominem. Eli makes history pleasurable, shooting him, certainly was.

When I delivered seltzer, never felt too much like a Sultan, myself, but I know what the Times meant and wouldn’t argue. How could i? In pictures, Eli is the Man of Seltzer, shows love for the business, while hiding pain so well, you might not also think of the challenges. I slung bottles at age 37 and it was a serious working-out, and now i know the great difference between the doubling of ages, and this makes Eli at 82 quite something.

But if Eli, was the Sultan of Seltzer, then I was the Shaman. Like Ronnie, I had that rare experience of a serious accident on the job, but, unlike Ronnie, it wasn’t the most obvious danger to a seltzer man, which is falling. I experienced the rare explosive side, got the life drained out of me, hoping I would come back, but never realizing the way it would sharpen what was already sharpened, and that being another burden itself. But that’s another story, but I’ll say this, I was doing honest work, as opposed to the work of professional artists, and it wasn’t a decision, to continue in this way, whether I liked it or not, my core would harden more. The job left a mark, after i left it to do this.

I worked for someone but folks like Eli own their bottles, vehicles and routes, but I was a paid as an employee of the company, and was paid by the number of cases delivered. The Long Island City, Manhattan-focused seltzer company that closed soon after I quit there, Gimme Seltzer, was mostly a Manhattan distributor of seltzer, and I had the downtown Manhattan route, a sea of walk-ups.

I know then, by experience, the difficulty of slinging cases of seltzer all day long. The Times said they were seventy pounds per case, but we always said, sixty. No matter, I’ve done a lot of basic labor jobs, and can say seltzer delivery is really strenuous. Sixty pounds on level ground soon becomes a vertical climb up steps that would get a heart beating very fast, and its only mitigation, was the amount of dough earned. If I owned my own route (company) that would have been the best pain-killer, and I can completely understand how that could make you, at a minimum, highly motivated to move seltzer, if not be in love with the business, and add in generational ownership and all that worth doubles. Even, as a piece worker i made decent money, and my 200 a month apartment, nearby in Williamsburg helped.

Plus it was being, as honest working folks, as opposed to, let’s say, professional filmmakers, photographers and artists, I Started doing basic labor jobs in 1968, and I know what I’m saying and have something to compare things to.

Eli and all the remaining seltzer men who work out of the Gromberg Works, own their vehicles, bottles and routes, and the remarkable Gromberg Works supplies them with the seltzer, filling their bottles with machinery over 100 years old. When I was shooting these guys, what became immediately apparent was a great attitude about their jobs, because it was a business they owned, was appreciated and had history. Eli and Walter Backerman probably went beyond that, in love for seltzer, since it was such a generational family thing. Eli, sometimes to my chagrin, in most every shot, he’s constantly promoting seltzer. We see no pain, unless he speaks of it, only his message he wants delivered – drink seltzer.

I initially wanted to go out on routes, so folks could see the level of grunting labor it takes to deliver hundreds of cases of seltzer on a daily basis, and I regret I didn’t, but was so involved that year in the 2013 closures out at the Junkyards in Queens, and all the other places that were closing, never to reopen again, but I never forgot what I should have done. In light of that, and from experience seltzer delivery is purely physical labor, the defining characteristic of the job is hard, focused labor. I can’t stress that enough, the physical labor. Because that is it, and that is really easy to understand, not complicated but purely seen.

In weirdly p c times, i say these were largely Jewish, blue-collar men, all of whom were smart and classy people, who could do anything because of that, yet sustained themselves with pure bull labor, in a mostly Jewish business of New York seltzer and still do, with the exception of Eli, now gone.

And, of course the tradition lives on since the young Gromberg, who runs the Seltzer Works Department at Gomberg, has taken over Eli’s route, and who better a man than another man that was born into the business.

Connection, having done what I shoot, is often the case. I was a seltzer man in Manhattan back in 1989. It was a stepping stone job, for me, and not a career, like it was for Eli, and all the drivers who I met at the amazing Gromberg’s Works in Brooklyn, the last surviving true New York seltzer works, 24 years after my days slinging seltzer in Mnahattan. Seltzer work left a deep impression, I mean, literally and physically, while giving an inside look at this historic native city business.

Eli Miller was a living kind of history, that, combined with his character, drew the right kind of attention – from people who won’t forget him.

Eli Miller

Listen to the siphon filling machine, a Barnett & Foster seltzer machine

Eli with his cases and bottles. Drivers usually own their own bottles.

Stacking cases.

Eli, Mike and Steve who is a seltzer man from Long Island.

Seltzer makes you happy.

Pushing his freshly-billed bottles to his truck.

The load is done.

Healthy and happy, is the life of a seltzer man.

The joys of physical work?

Listen to Eli’s greeting on his phone message machine.