How do hazardous waste dumps emerge in the middle of cites and neighborhoods in the Rust Belt over time? I can tell you and show you by way of experience, the same way, someone who dwells in any area can.

The World Waste dump in the Forgotten Triangle, a section of Cleveland comprised of sections of five different neighborhoods, that, geographically and by street design form a large triangle with smaller triangles located within.

As an expert in these sorts of things i would have to say that the Forgotten Triangle is the largest, most forgotten place I have ever been while inside a city.

This site and a few others were cropping up faster than normal around 2009. The city and county were starting a program, now funded, to take out every abandoned building in the city, and, as a result demand for getting rid of the debris rose, in a city full of empty lots and abandoned structures. Recycling dumps, on the surface makes sense, or, at least plugs into the prevailing trends of a green economy. Turning brownfield and old unused industrial buildings into storage areas seems to makes sense as well, and, with the city also embarking on a massive demolition project that would take out literally all of the abandoned properties in the city, it seems to make even more sense. The debris from housing demolitions are now remediated so the debris is supposedly non-toxic, and it’s a “green” project because some recycling will be done. But those are concepts that, in reality, are bull shit.

And with no oversight, and really no thought about the consequences or qualifications of the dump owners, in fact, the whole idea of reusing old industrial lands and buildings is completely bankrupt of any sense or common good, but does reflect the greed and duplicity by the dumpers and dump owners, and the stupidity and desperation of a struggling city. Recycling of non-toxic waste? Are you kidding? The debris accumulates. The property owner makes money, if, then, a disaster occurs or not – they always split out and the city is left with the clean-up bill. It’s all done out of the greed of dump owners that combine with a city’s desperation and an era’s lame values of a hipster utopia of urban farms and recycling.

By 2019 recycling industry is pretty much dead, so when it works, it’s because of the right market conditions that come and go.

And the fact that within these cities there are sections that are so downtrodden and forgotten, that felonious pollution of the worst sort goes on in broad daylight, that, if anyone cared, would only take a brief look to understand. RealStill has been living and working in these forgotten places since they began as such.

THE CLEVELAND AUTOMATIC MACHINE COMPANY

The Cleveland Automatic Machine Company, 1980. Two years after the birth of the Rust Belt. If these were ruins shot yesterday they would still look the same – that’s the thing about ruins, no matter the year shot, or nearness to the closing date, It always could look like any year. Ironically, the structure was torn down soon after this, and immediately became an outlaw open-air dump minus the buildings. It’s still a dump in 2019, but has all the permits and is strictly limited to solid construction debris, like concrete, now piled as jigh as the former factory.

On the surface utilizing exisiting abandoned structures to store and tranfer non-toxic waste for recycling sounds perfect, excluding nature.

Not long ago, in the ghetto, that’s progress.

Using closed or abandoned factories for either storage or dumping is nothing new. Old manufacturing facilities like this with a long glorious history of manufacturing, they close, and sometimes used by small new companies, but then fail themselves, and the only use left is to reset the space as a waste facility. No matter, if the facility just simply shuts down the dumpers wlll still use it, it’s is part of the broke-down logic of bankrupt cities.

The last manifestation of the old Cleveland Automatic Machine Company was another waste paper storage and recycling facility.

Back in 1980 using useless factories to “recycle” paper caught on with the ecological angle combined with desperation. Employing no one and contributing nothing to the city, they only echoed the impossibility of the Rust Belt economy, particularly during its first years. A very few tried to shine a light on it, but there were a lot of big problems back then, and there was no media fragmentation, liike today.

Only a strong economy that thwarts population loss and broke cities, works, nothing else. My original premise, that the golden age of American cities was ending and wasn’t going to return – was an an early determination that set me on a path of capturing the soon-to-vanish. Often the last desparate use for industrial properties is dumping. or, at best, storage, and is a strong sign of the growing impossibility of manufacturing in urban areas.

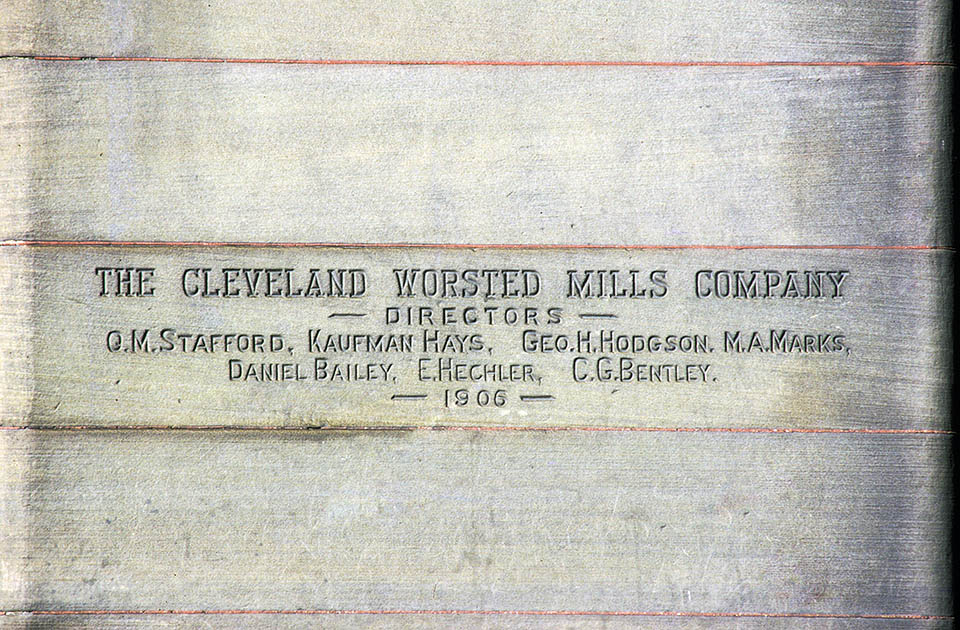

CLEVELAND WORSTED MILLS

Before the Rust Belt, we can see the roots of pollution dumping at industrial sites with the old Worsted Mills Plant. It was closed, not due to poor economic conditions, but its history of stubborn recalcitrant owners who just shut the facility down rather than deal with unions or the government. This was in the 1950s, and the company ceased production becoming a warehouse that employed no one.

As the industrial economy slowed in the 70s, the only use for an old factory would be warehousing and storage. Not originally designed for this, there was no sprinkler system throughout the entire complex, and with buildings this size, who knows what ends up being stored there?

On July fouth, 1993 the entire structure burned in an arson fire. Unknown dangerous chemicals were stored there and took the blame.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wzghjiv3bP0

The back end of the Cleveland Worsted Mills Plant in 1982. Today everything in this shot is gone. The smoke stack to the right i part of the old powerhouse for the factory. Today the section is becoming a nature preserve, but otherwise the site still sits as empty land. Notice the houses at the left hand corner of the factory, no doubt a Polish family, back in the day, even today, lives there, but without your job right outside your door.

The Worsted mills were closed In 1955 over a union beef. From there on in the facility was used for storage and warehousing. A fire in 1993 completely destroyed the facility. They say it started in area where 100 barrels of suspected toxic waste was illegally stored. The entire facility was without fire prevention sprinklers, so It succumbed.

The city had to pay $4 million clean the site up after the fire.

Pediment over entrance to the Plant on Broadway Avenue. They certainly don’t these things in a classical style that symbolized permanence and longevity that, of course,In the case of industrial structures from ove one hundred years ago, was, in fact, quite an illusion.

O.M Stafford who create Worsted out of Turner Textiles was also a banker whose large neighborhood bank was just blocks away. Today and since the seventies it’s home to Hubcap heaven a well-known used hubcap dealer.

Also this history including the pollution is our industrial legacy in real terms and documented.

Dedication plaque on Broadway Avenue.

Mr. Stafford had a colorful career and is seen as a kind of early “Trump” figure, but his own times had plenty of Trump-like characters. This company would end up being run by Poss who was more Trumpian than others before him, and it was him, in a final act of self-destruction who closed his functioning profitable historic plant over a beff with unions.

Realizing the anti-government, anti-union, ethnic favoritism and love for unfettered capitalism in the company’s history, its ending seems preordained and is certainly a lesson in self-destruction as government protest.

The roots of how something ends up a waste site, then dies has been documented with the Worsted Mills history, and, although, closed, because of the owners’ hatred for both the government and unions, the Rust Belt guaranteed that there would be no other viable alternative but to use the facility for the storage of something, or get rid of it.

THE JORDAN MOTOR CAR COMPANY

Jordan Automobile Company the most interesting of American car manufacturers in the 1930s. Its buildings used as warehouses and its water tower, as a tribute to the local football team.

In 2007, what was left of the original structures was demolished as a line of old industrial properties, divided up into some smaller companies and warehousing, went up in flames, like Worsted Mills, burned in a spectacular fire.

“As we drove from East Cleveland across Woodworth Avenue into Collinwood we would pass (on the left, or west side of E. 152nd) the Towmotor Corporation, the company that invented the fork-lift truck, and where my dad was a highly skilled and well paid tool and die maker. Then on the right GE’s big factory that produced light bulbs and such. Then again on the left the Clark Equipment company, which also made, among other things, towmotors! Over the little railroad spur track and next on the right was the factory of the Murray Ohio Manufacturing Company, which made those wonderful Murray bicycles such as the snappy red and white model I was so proud of which dad and mom bought for me a stone’s throw away at Western Auto’s Five Points store.” – Robert Dreifort

THE FORGOTTEN TRIANGLE

A lone tree surrounded by ground up, freshly demolished homes along East 83rd Street. The site evolved into a dump for housing demolitions and lastd about three years, before its clean-up.

The Forgotten Triangle is huge swath of land comprising sections of five different neighborhoods in the east side of Cleveland. The Triangle’s heart is an area that was known simply as Buckeye and was the largest concentration of Hungarians outside of Hungary. Typical of the city’s industrial neighborhoods, the homes and residential areas were dwarfed and set into heavy industry and connected by a tangle of transportation infrastructure including many bridges and rail lines including a huge switch yard and maintenance facility in the midst of factories like the Van Dorn Iron Works, Eberhard Manufacturing, National Maleable and numerous industries. Historic pictures and my own history testify to the amount and level of loss that the Triangle represents. If you would look at old photographs of the area this description would come to frozen life. It was incredibly built up – and quickly to accommodate the poor immigrants arriving en masse, but their enclaves, as populous as they were, became that way because of the factories and transportation in the area that took up the great majority of land. The Triangle started to become truly forgotten in, when, on a hot dry windy summer night, May 5, 1976, a fire started at 8210 Dawn Avenue, a home that had a tangled family ownership and had not paid its taxes since 1968. The house ignited during a hot dry spell during the seventies and in the firestorm that ensued 28 homes were destroyed. Coincidentally arson fires would peak at an all-time high for the city in 1979, and was similar to the South Bronx where some owners felt they had one last way to squeeze their money out of an impossible investment. And, because of budget problems, firefighters were also being laid off at the time. If that wasn’t enough, there was bad water pressure the night of the fire, from the city’s aging infrastructure, and, in three hours, sixty families were homeless.

By 2010, the original neighborhood of Hungarian immigrants from the 1880s and the heavy industry, was entirely gone. In the sixties the area’s racial composition began to shift, and the Triangle started to evolve into a completely black neighborhood by 1980, and, at this time, the area was old, but functioning and present. With the Rust Belt kicking in, taking out even the strongest of industries, nothing much was left by 1990, and, by 2010 nothing was here from the old days of industry and ethnic enclaves. When i say there was a black population, overall it was tiny since nothing really was left, and, in fact, of course, there were folks of other stripes, but, like i said, it’s insignificant.

East 81st Street is a dead end street lined with factories that had shutdown in the eighties and nineties and became an ideal concealed dumping ground.

World Waste was another short-lived dump on East 83rd Street where Cleveland’s recently demolished houses were dumped. All this was part of the old long-gone Ashland Oil Company, and ended up as a storeyard for ground up homes.

VIKING STEEL

The Old Viking Steel Plant at East 166th Street and St. Clair Avenue that became another waste paper recycling facility, and the kind of place that employs very few people, pays little in taxes and gets away with profits and masks all sorts of activities. This facility was run by the same company whose practices would finally come to light at the the National Acme Plant, in 2014, another old large closed manufacturing facility in nearby Glenville used to dump waste illegally on a grand scale, but sold as another green recycling project.

NATIONAL ACME

The plant was distinguished by its size, array of skylights and bays of windows. The National Acme Plant at Coit Road & Taft Avenue was constructed in 1911 and ws built in a factory zone straddling the Glenville and Collinwood neighborhoods where giant auto and auto parts factories and assembly halls were no big deal, in fact the Chandler Auto Plant was next door to National Acme, Fisher Body just blocks away, and the Grant Automobile Company directly across the street on Kirby Avenue.

It hung on as a storeroom for the company in the eighties but was shut entirely shut by 1993 when it sat in undisturbed organic descent until bought by a crooked contractor.

Unfortunately the man who owned Global Waste at the old steel mill on St. Clair became the owner, and he promised another waste recycling facility for the site. He took in anything until he filled the factory floor, and then, conveniently began to demolish it, illegally, until they were caught. But the shop floor, a massive, high-ceilinged, single story assembly room, lit by rows of skylights on the roof and large bays of windows on the walls, was destroyed. They had been dumping inside, the place had gotten full, and they decided to tear it down without any permits, inspections or permissions.

Christopher Gattarello, who leased the building in 2011 and used it as a storage facility for thousands of tons of paper, cardboard waste and municipal garbage, was sentenced in July to 57 months in federal prison.

Nugent ordered Jackson to pay more than $6.6 million in restitution to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which did some cleanup on the site to remove exposed asbestos, and the city of Cleveland, though it’s unlikely either will see much of that money.

The cleanup will cost at least 7 million and there is still tons of garbage at the site with the buildings wide open in ruin, in the Glenville neighborhood that already is about as troubled as any place can get. In 2021 a lot of waste still remains.

The roof and skylights sit unceremoniously on a floor of garbage and waste.

Where hundreds assembled machine tools for one of the dominant tool makers in the world, now stands waste of all sorts.

The plant lies in ruins because it was purchased and, without permits, remediation or any notice to the city, went into full demolition, and, by the time it was discovered, not only, was it an illegal demolition, but had been an illegal dump for anything including garbage and asbestos.

The grounds and buildings had become filled with so much debris, garbage and waste that a quick under-the-radar demolition might be the only way to hide the proceedings.

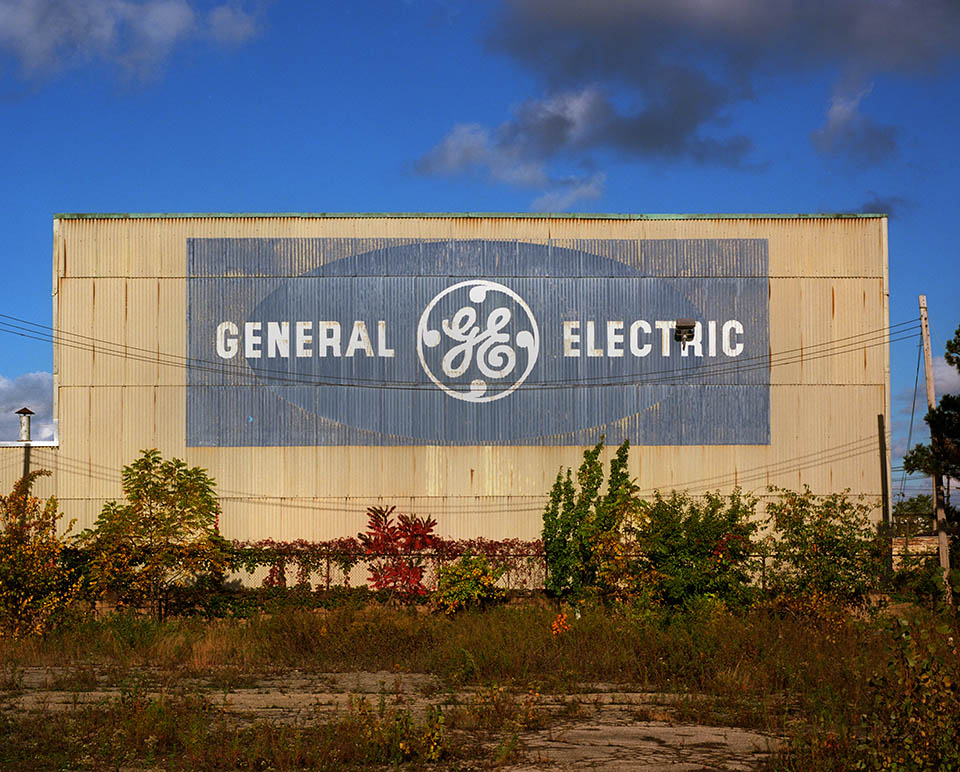

GENERAL ELECTRIC

The General Electric Lamp Plant, sitting downhill and across the street from the Nela Park Campus of GE. This empty lot was a Manner’s Big Boy restaurant and had its hospitality school. Just to the right was a movie theatre, the Euclid, and shops, and to the left were more shops.

The plant closed in the early nineties, but was never torn down. On the other side of railroad tracks to the north is another larger, older and closed GE factory, that still stands today. GE eventually tore the plant down and gave the land to the city of East Cleveland.

The General Electric Company had a huge presence in and around East Cleveland, and the Nela Park campus is still functioning today, that is remarkable since Nela Park was all about lamps and bulbs, one of the most transformed products. GE never would let what occurred, after they donated the land to the city of East Cleveland, who, in 2016, sold it to a recycling firm for $175,000.

Arco Recycling claimed they were going to recycle clean waste that would be only demolition debris from remediated houses being torn down in a flurry of demolitions, which mades sense on paper alone. It became the typical spiel about an environmentally friendly business trying to do something about the problem of all the houses in this city that are being demolished, and do it in a clean way.

Normally homes the butt up against any sort of abandonment or waste sites are the first to be abandoned in any neighborhood, but for some reason all the abandoned homes are across the street, probably that, before the dump, a large closed GE Light Plant was there, and there had always been a large parking lot serving as a buffer zone to the plant that was non-polluting to any neighbors.

Lots of people living in the duplexes on the east side of Noble Road, with increased abandonment across the streetbecause of the bad environment.

Homes have been abandoned across the street on the west side of Noble Road, and locals have usd them to express their hopes and desires – simply to get the basics. They pay their taxes, many have livd here, renting their upstairs units since 1980.

This is the long ignomius end to an industrial history that made this city an epicenter of technical innovation and manufacturing beginning in 1911 with Nela Park, and much earlier in all the nearby factories in neighboring Collinwood that were pumping out, for instance, as many automobiles as Detroit.

The rows of duplexes on Noble Road are the only homes that touched the waste site, and the old GE plant. The homes sit less than a half mile from Nela Park – the first industrial park and corporate campus in America. The big clean plant that these homes shared a fence with – a General Electric bulb plant when you could walk to work, was an extension of the research being done at Nela Park, just uphill where, things like the first CFL bulbs were invented.

A line of functioning duplexes along the west side of Noble Road that is directly across the street from the GE Plant that became the Arco dump. Today a portion of the these homes have been abandoned and there is a general deterioration, that this section of Noble Road has avoided up until the arrival of the dump.

This city has been run by the people who live here as it always has been. The wild card was the Rust Belt that took away the jobs. That coincided a few years after the city changed on a race level. The GE Plant had been closed for 15 years and sat idle across from these homes. The company gave the land to the city after the plant was demolished. The city sold it to Arco Recycling for 175,000 dollars. It lasted two years and its cleanup ended up costing 7 million dollars.

These homes survived the entire span of the Rust Belt, and, in place like EC, that’s remarkable. Today the line is snaggletoothed as homes have been abandoned, being hard to rent, or live in across form a notorious dump.

How could it happen? RealStill has explained it. I often asked how could all the Robber Baron corporations get away worth pollution and toxic waste. Witnessing the rise of fracking or tech companies out west – money.

It’s opposite – extreme lack of money and decline, allows dumps through time.

You can yap about the big trifecta – race, religion and gender – but how many of you have experienced what they are so opinionated on, let alone document it, work in it, for over forty years, and put your money where your mouth is? As opposed to watching it on your screens.

Always about economics. A city progresses by adapting and moving forward with fresh blood, that is solely dependent on attracting fresh blood to keep it all going. Stagnation alone is considered a quagmire in most cities, but there are only a handful of cities that have gone this far down economically, and been this dysfunctional and broke. We see these desparate politics, years of misery for residents and it effects the entire county by virtue of the fact that East Cleveland, for the sum of 175k gave a lage tract of land to a shadey comapny that resulted in a clean-up by the county costing 7 million dollars, and screwing up the lives of the city’s residents.

This is what goes on with urban dumps throught time.